Cognitive Dissonance, Motivated Reasoning, and Confirmation Bias

Dorothy Martin awoke early one morning in her suburban Chicago home. Her whole arm was tingling. She didn’t know why, but she picked up a pencil next to her bed and started writing. The words that flowed onto the paper were not her own. Even the handwriting was different.

She was receiving a message, a prophecy, from Jesus, currently living on the planet Clarion and going by the name Sananda. Sananda and the other aliens, or Guardians, told Dorothy that she was to spread their messages and teach others how to advance their spiritual development.

The 54 year-old housewife told some friends about her experiences, and the word spread. Soon she and her fellow Seekers were meeting regularly to hear the latest messages from the Guardians.

On the morning of July 23, 1954, the Guardians sent Dorothy a message. Gather the Seekers. A spaceship would be landing nearby at midday.

A faithful dozen followed Martin out to an air force base to witness the event, but no flying saucer came. However, they noticed an odd man on the road. He had a strange look in his eyes, refused food and drink, and disappeared as mysteriously as he had appeared. Later, Martin received another message. The man had been Sananda in disguise. Martin was euphoric.

In late August, Sananda again spoke to Martin. This time the message was dire. A huge flood was going to destroy the world. Doomsday was approaching. However, the Guardians would come to rescue the chosen ones and take them away in their flying saucer.

The Seekers were told to be prepared for rescue. Many quit their jobs and left their families to move in with Dorothy. And although the flood wasn’t expected until December 21, the followers were told to be ready. The Guardians could come for them at any moment.

On December 17, there was a phone call from Captain Video from Outer Space, who said a flying saucer would be landing in Dorothy’s backyard at 4:00 pm. One of Dorothy’s previous messages had warned that no metal could be worn on a flying saucer, or it would react with the aliens’ power field. So in frantic preparation, they removed all of their jewelry, tore out their zippers, and pulled the wires out of their bras. (None of them seemed to notice that Captain Video and His Video Rangers was a popular TV series at the time.)

At 4:00 pm the Seekers were in Dorothy’s backyard awaiting the arrival of the Guardians. Around 5:30 pm they went back inside, shocked and disappointed. Then another message came from Sananda, praising their dedication. It had only been a practice session, to make sure that when the time arrived, things would go smoothly, and they wouldn’t make any mistakes.

On December 18, Dorothy got another message. The aliens were coming. Immediately. Everyone quickly scrambled outside, once again removing all of their metal. But again, no flying saucer landed to take them away. Some members of the group privately worried that the reason they hadn’t been rescued was because they had metal teeth fillings.

But they reminded themselves that the real rescue would take place at 12:00 am on December 21, as predicted in the original prophecy.

So the Seekers prepared. They took off all metals. They bundled their “Sacred Books”, transcriptions of Dorothy’s messages, into shopping bags to carry onto the spacecraft. And they waited in tense silence for their ordeal to finally be over.

At five minutes past midnight, the aliens had not yet arrived. Someone in the group reassured everyone. The clock was wrong! Five minutes later, Dorothy announced that there was a slight delay in the plan. At 2:30 am, Dorothy received a message. They should take a coffee break.

At 4:00 am the group sat in silence, faces frozen and expressionless. What had they missed?

But another message came at 4:45 am. Good news!!!! Because of the actions of the Seekers, God had decided to spare the planet from destruction.

Their dedication had saved the world!

Self-protection through self-deception

Psychologist Leon Festinger was reading the morning newspaper in the summer of 1954, when he stumbled upon a short article about Dorothy Martin and her apocalyptic warnings from extraterrestrials about a civilization-destroying flood approaching on December 21.

Festinger wondered what would happen on December 22, when the world hadn’t ended and no flying saucers had appeared. To find out, he and a few other scientists infiltrated the group by pretending to be believers and recording the events and the believers’ reactions.

Source: Is a claim true? Use these four criteria to evaluate the evidence

Fascinatingly, when the prophecy failed, rather than admit they were wrong, the Seekers became more convinced they were right.

Festinger explained this apparent contradiction with his theory of cognitive dissonance. Essentially, we all have an inner need for our beliefs and behaviors to be consistent. Any inconsistency is uncomfortable and needs to be resolved. So when we’re faced with evidence that threatens a deeply-held belief, especially one that is central to our identity and worldview, rather than changing our mind, we double down.

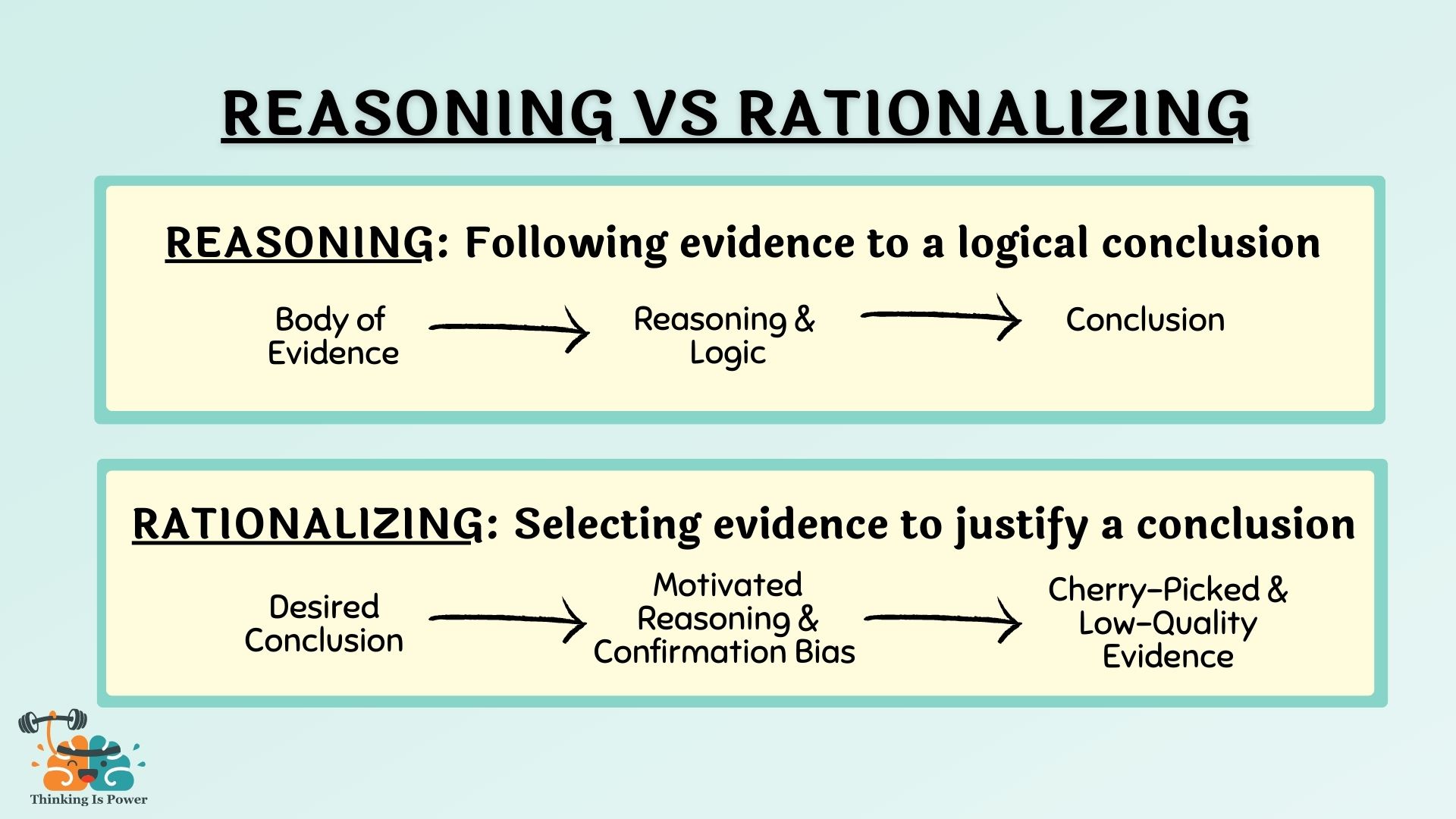

Our emotions take over and we engage in motivated reasoning to help us justify our belief or rationalize our behavior. We use confirmation bias, and search for arguments and evidence that support the conclusion we want to believe, discounting and discarding those that don’t. These mental gymnastics ultimately help us reduce dissonance while maintaining our desired belief.

For example, Tabitha knows that smoking is unhealthy, and yet, she smokes, leading to an uncomfortable tension that needs to be resolved. One option would be to stop smoking… but that’s difficult. She’s more likely to change her belief, or add a new belief to help her rationalize continuing to smoke. She might tell herself that her grandfather smoked his whole life and was fine. Also, she eats healthy and exercises. Plus, she only smokes low-tar cigarettes. And not very often.

The Seekers were faced with a dilemma. They believed the world would end, yet it didn’t. They couldn’t give up on the first belief, because they had invested too much in it. They had publicly committed themselves, and had attempted to convert friends and family. Many had given up their money, and even left jobs and spouses.

Yet they also had to accept the second belief that the world didn’t end. Because, well, it didn’t.

So, they resolved their dissonance by adding another belief that helped them rationalize their actions: they had saved the world through their unwavering belief and heroic actions.

Why it’s hard to change our minds

When faced with evidence that contradicts a deeply held belief, we don’t change our minds. Instead, we act like lawyers trying to win our case and prove ourselves right.

To make matters worse, our current media environment allows us to avoid dissonance altogether, by surrounding ourselves with like-minded believers and information that reinforces those beliefs.

The real question is, which is more important to you? Defending your beliefs? Or understanding reality?

Our beliefs are often based in emotion and tribal identity, not on an objective evaluation of the facts. (If you think that’s not you, it’s probably you.)

Plus, the more we’ve invested in a belief, the more invested we are in maintaining the belief. We don’t want to think we’ve wasted time, effort, or money.

And if the belief is important to our identity or social standing, we are even more motivated to protect it. Dissonance is the strongest, and most painful, when it threatens how we see ourselves.

But cognitive dissonance is our brain’s way of telling us we might be wrong. Reality doesn’t care what we believe. Smoking is harmful to our health whether we accept the truth or not.

So to make better decisions, we need to think better. Metacognition, or thinking about thinking, and intellectual humility, or recognizing we might be wrong, are essential.

Don’t get defensive. Learn to live with uncertainty. Recognize the limits of our knowledge. And be open to changing our mind.

Easier said than done!

The take-home message

We all like to see ourselves as intelligent and rational. We don’t like to think we can be fooled. Or wrong.

Our beliefs become part of our identity, and we share those beliefs with others in our social group. The more time or money or emotions we‘ve invested in our beliefs, the more motivated we are to protect them.

When we’re confronted with evidence that we’re wrong, our brains find ways to justify the belief and protect our social standing and the positive way we view ourselves.

So, we surround ourselves with others that agree with us, and actively seek out information that confirms our beliefs. And we don’t change our minds, because that would mean we were wrong.

In other words, we deceive ourselves because it feels good.

When the aliens didn’t come to rescue the Seekers, they doubled down on their belief rather than admit they were wrong.

The question is, when the aliens don’t come to save you from global destruction….will you change your mind?

To Learn More

When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group that Predicted the Destruction of the World, by Leon Festinger, Henry W. Riecken, and Stanley Schachter

The Atlantic, The Christmas the Aliens Didn’t Come

Opinion Science Podcast, Cognitive Dissonance: A Crash Course

New Yorker, Why Facts Don’t Change Our Minds

The Atlantic, The Role of Cognitive Dissonance in the Pandemic

Thanks to John Cook, Lynnie Bruce, and Anthony Trecek-King for their feedback.

Pingback: 2021 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #36 | Climate Change

Pingback: The Person Who Lies To You The Most.... Is You ...

Pingback: The Person Who Lies To You The Most…. Is You | Climate Change

Pingback: Najbardziej okłamywani jesteśmy przez samych siebie - naukaoklimacie.pl

Pingback: Skepticizam kao zaštita od obmane: Priča o duhovima iz stvarnog života - FakeNews Tragač

Pingback: Wie Skepsis dich davor schützen kann, getäuscht zu werden

Pingback: Sechs wichtige Fragen zur Faktenüberprüfung deiner Überzeugung

Use correct English. For instance, write “centered on,” not “centered around.” The latter makes no sense.

Thank you for kindly correcting my English. I do make mistakes. However, I checked and “centered around” is a generally accepted idiom.

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/centre-around-on

I think the source for this is “when prophecy fails”. If so it would be good to state the source in your references.

You’re right, of course. That was a major oversight on my part. Thank you!