The Limits of Knowledge and the Dangers of Certainty

Twenty-two year-old college student Jennifer Thompson was asleep in her apartment on a hot July night in 1984, when she was awakened by a noise, and then a man pinning her to the bed with a knife to her throat. He threatened to kill her. And then he raped her.

During the attack she made every effort to remember as much detail as possible, including mental notes of his face and outfit, so if she lived, she could have justice.

After going to the kitchen for a drink, she escaped out the back door and ran to a neighbor’s house.

At the police station she gave a detailed description of her attacker. News reports asked viewers to help find the suspect, a Black man in his early twenties or late teens, around six-feet tall, approximately 170 pounds.

The next day the police got a tip that a man who worked at a restaurant in the neighborhood, Ronald Cotton, matched the description.

Ronald had been convicted for attempted rape when he was 16 and was out on parole for another conviction for breaking and entering. His boss said he was in the habit of touching the white waitresses and that he owned a blue shirt similar to the one Jennifer saw during the rape.

In a search of Ronald’s home, police found a pair of black shoes and a flashlight, both similar to those described by Jennifer. His old shoes were beat-up and matched a piece of foam rubber found at Jennifer’s apartment.

Ronald told the police he was out with friends on the night of the attack. After detectives were unable to confirm his alibi, he changed his story and said he was with his girlfriend at a motel. Later, he changed his alibi a third time saying he had his dates mixed up and he was actually at his mother’s house.

But most damning for Ronald was Jennifer picking him out of a line-up. She had made sure to remember what her attacker looked like so she could put him behind bars.

And she was absolutely confident that Ronald Cotton was her rapist.

So was the jury. There was evidence, a suspect with a prior conviction and no solid alibi, and confident eyewitness testimony.

Ronald cotton was convicted of rape and sentenced to life in prison.

The Nature of Knowledge

We often think we “know” a lot of things. Some of us are even quite confident in what we think we know. But what is knowledge?

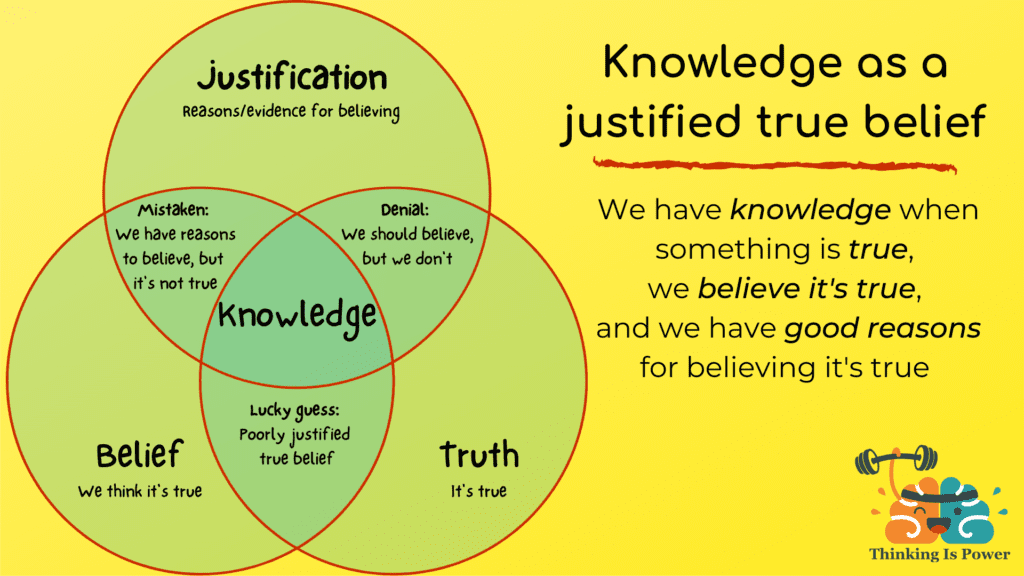

A very simple definition of knowledge is that it is a justified true belief. Meaning, it’s true, we believe it’s true, and we have good reasons for believing it.

Central to this definition is how we know something. Essentially evidence matters, and the better our evidence, the more justified we are in believing.

But individually, we rarely know enough to have good justifications for most of what we believe. Remember that we often come to believe things in irrational and unreliable ways. We trust authority figures and members of our group. We believe what we hear. And we really trust our personal experiences.

Additionally, once we accept a belief, we engage in confirmation bias, where we search for evidence that supports our belief and ignore evidence that doesn’t. As a result we often deceive ourselves into thinking we have more evidence for our belief than we actually do.

The question is, do we want to believe in things that are true? And not believe things that aren’t?

To many, the initial reaction is: Yes, of course! But sometimes the truth is uncomfortable.

If we really want to know the “truth” – to the best of our ability to know what’s true – we shouldn’t be afraid to question our beliefs. After all, truth withstands scrutiny. So what evidence would prove you wrong?

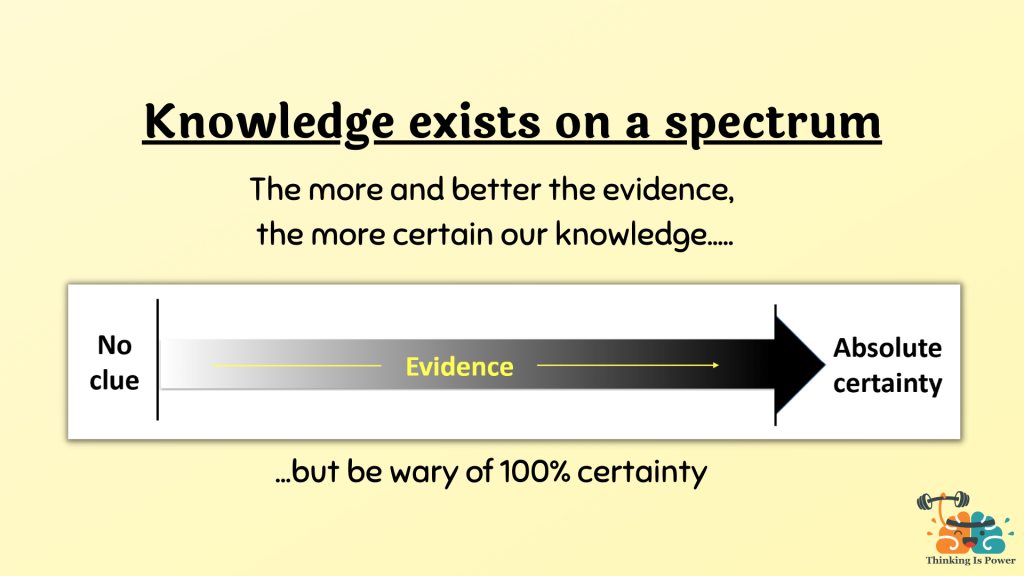

Finally, knowledge isn’t black or white. It’s a spectrum, with many shades of gray. But as 100% certainty is nearly impossible, we should avoid being overly confident… we probably don’t “know” as much as we think we do. And if we’re too confident, we won’t be open to new evidence or changing our minds.

She Was Wrong

Ronald Cotton never stopped proclaiming his innocence. He spent his days writing letters to lawyers, newspapers… anyone who might listen and be able to help.

Ronald had been in jail for about a year when Bobby Poole joined him working in the kitchen. Bobby resembled Ronald, and was serving several life sentences for a series of rapes. Bobby even bragged to other inmates that Ronald was serving time for his crime.

Eventually, the case caught the attention of law professor Rich Rosen, who noticed the relative lack of evidence against Ronald, and was aware of the limitations of eyewitness testimony. Rosen was able to use newly available DNA testing on fluid samples from the crime scene.

The DNA not only cleared Ronald Cotton, it found the rapist: Bobby Poole.

In the spring of 1995, eleven years later, a detective stopped by Jennifer’s house to tell her the news. It wasn’t Ronald Cotton that raped her, it was Bobby Poole.

She was shocked. She had been so confident that Ronald had raped her. For years she had been haunted by images of Ronald’s face during the attack.

Yet she was wrong. Science had proven it was Poole.

Jennifer couldn’t believe she had sent an innocent man to prison for eleven years.

A few weeks later, Jennifer and Ronald met in a church and talked for two hours. She wanted to tell him how sorry she was. And he forgave her. Today, the two good friends travel the country to promote criminal justice reform.

Bobby Poole died of cancer in prison in 1999.

The Take-Home Message

The better our evidence, the more justified we are in believing. However, we are often overly confident about what we think we “know,” as it’s nearly impossible for any of us to have sufficient justifications for the majority of our beliefs.

We’re more likely to gain real knowledge when we recognize the limits of what we know, learn to be comfortable with uncertainty, and are open to changing our minds. Trusting those with better knowledge (ie experts) is an excellent short-cut.

The bottom line is, we really don’t know as much as we think we do. And that’s okay.

To Learn More

Intellectual Humility: The importance of knowing you might be wrong (Vox)

Intellectual Humility: The ultimate guide to this timeless virtue (Shane Snow)

The Perfect Witness (Death Penalty Information Center)

What Jennifer Saw (PBS Frontline)

Thanks to John Cook, Lynnie Bruce, and Anthony Trecek-King for their feedback.

the inquiry/questioning methods used by investigators was not revealed in story of Jennifer Thompson. I mention this as biases impact the inquiry/questioning thus the outcome.

Pingback: La certitude nous empêche-t-elle d'accéder à la vraie connaissance ? - CITIZEN4SCIENCE

Pingback: Tipps zur Faktenüberprüfung: 6 wichtige Fragen, um herauszufinden, ob deine Überzeugung stimmt

Pingback: VIER GRÜNDE, WARUM ANEKDOTEN KEINE GUTEN BEWEISE SIND

Pingback: 6 WICHTIGE FRAGEN ZUR FAKTENÜBERPRÜFUNG DEINER ÜBERZEUGUNG

Pingback: Four Reasons Why Anecdotes Aren’t Good Evidence

Pingback: 6 Key Questions to Find Out if Your Belief is True