You’re Not As Rational As You Think You Are

Every year on February 15, on an isolated island in the middle of the South Pacific, members of the Tanna Army worship god by marching in military-style parades. They wear red, white, and blue, paint USA on their chests, and march with bamboo “rifles.” The American flag is flown. Patriotic songs are sung.

Because on this island in the Vanuatu archipelago, god is an American soldier. And his name is John Frum.

How exactly this religion began is still not fully known. By some accounts, John Frum first appeared on Tanna around 1930, in full American military regalia, promising them that if they reclaimed their traditions and customs, he would return, and bring them wealth and goods.

The Melanesians, living on the isolated islands for two thousand years, had developed unique traditions, customs, and beliefs. After Europeans “discovered” the islands, the British and French claimed them as colonies. Christian missionaries quickly followed. Though the Tannese were poorly treated, disrespected, and overworked, they tried to maintain their culture and traditions.

Then, during the fight against Japan in World War II, the U.S. military implemented a strategy of island hopping. Once a base was built and sufficient cargo brought in, they moved on to the next island. And because the focus was primarily on smaller and less guarded islands, populations that had previously been isolated were exposed to the “magic” that is modern technology. Planes. Guns. Medicine. Factory-made clothing. Canned food, like Spam.

Their Messiah had returned. The prophecy was true!

After the war ended, John Frum (possibly John From America) left. But hopefully with enough celebrations, prayers, and symbolic offerings, he will return, and bring more goods with him.

This belief system might sound strange to you. I heard it for the first time while visiting Vanuatu, after noticing make-shift runways and “airplanes” made out of grass, and I will fully admit to an involuntary head tilt.

But consider how Chief Isaac Wan responded when asked why, 60 years after John promised to return with cargo, followers still believe in him.

“You Christians have been waiting 2,000 years for Jesus to return to earth, and you haven’t given up hope.”

Hard to argue with that.

How do we form beliefs?

Source: Is a claim true? Use these four criteria to evaluate the evidence

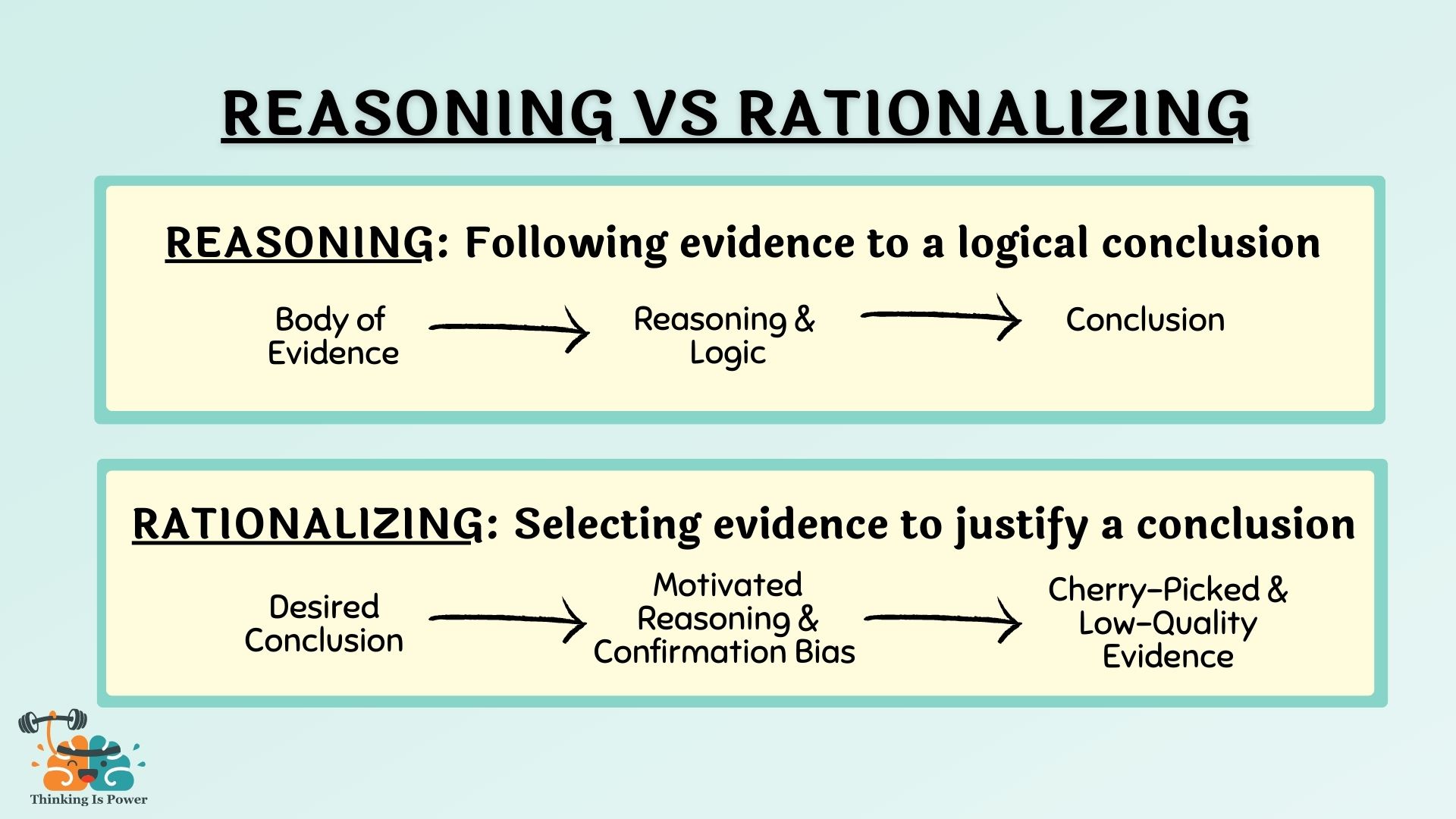

We like to think we are rational, and that our beliefs are the result of following evidence to a logical conclusion.

But we would be wrong.

Evaluating evidence takes time and energy, and our brains are lazy. It’s easier to believe what we hear than to question it.

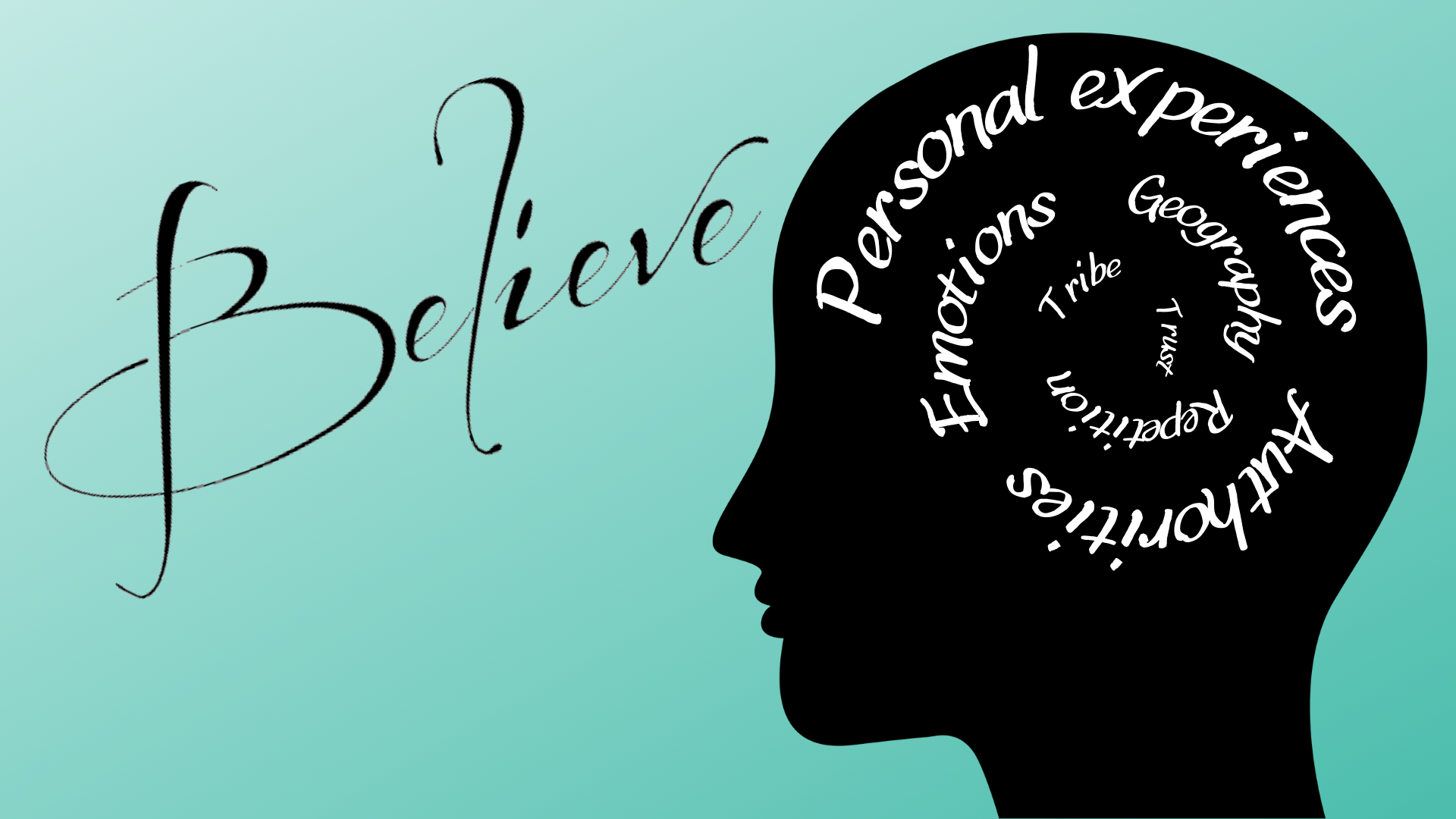

In reality, most of our beliefs are simply a product of socialization, trust, geography, and emotion.

And once a belief is formed, we don’t tend to change our minds.

We want explanations

Humans are naturally curious. If you’ve ever spent much time around a toddler, you’ve certainly heard them ask “But, why?” A lot. And our curiosity leads us to search for explanations.

Source: Gleilson Miranda/Secretaria de Comunicação do Estado do Acre

We look for patterns: Our brains are constantly trying to make order in a chaotic world, to connect dots in a way that makes sense.

For example, you’re up all night vomiting. What made you sick? The Taco Bell you ate for dinner?

Or you’re alone in the house at night and you hear a sound…Was it the cat? A burglar? A ghost?

Or imagine you’re hiking in the woods, and you hear a sound. Is it the wind? Or is it a mountain lion? Your life is on the line!

If you assume it’s a predator but it’s just the wind rustling through the trees, you’re alive. Paranoid, but alive. But if it’s actually a predator and you assume it’s just the wind, you’re dead. Basically, it’s adaptive to see patterns, even when there isn’t one.

We assume intentions: Our brains seek more than order. They seek meaning and purpose. Our belief in intentional forces likely evolved along with our pattern recognition…like the predator in the woods you assume is going to kill you.

For example, the child who asks “why?” often assumes there’s a reason or purpose. Why are there lakes? So we can swim in them! Why do birds exist? To sing us pretty songs!

We see this in adults, as well. For example, a hurricane was punishment from god. Or wearing your lucky socks will help you win the game. Or praying your that your computer didn’t just lose all of your work will save your paper.

Belief in the supernatural is likely due to agenticity, or the tendency to believe invisible intentional agents control the world. Because the natural world is complex and out of our control, we see the work of ghosts and demons and gods and witches. But not everything has a purpose or supernatural cause. Sometimes things just happen.

Believing is our default setting

We are inundated with information, all day, every day. It would simply be too exhausting to question every single thing. So as a rule, we don’t, and instead rely on a variety of short-cuts to determine what’s true..

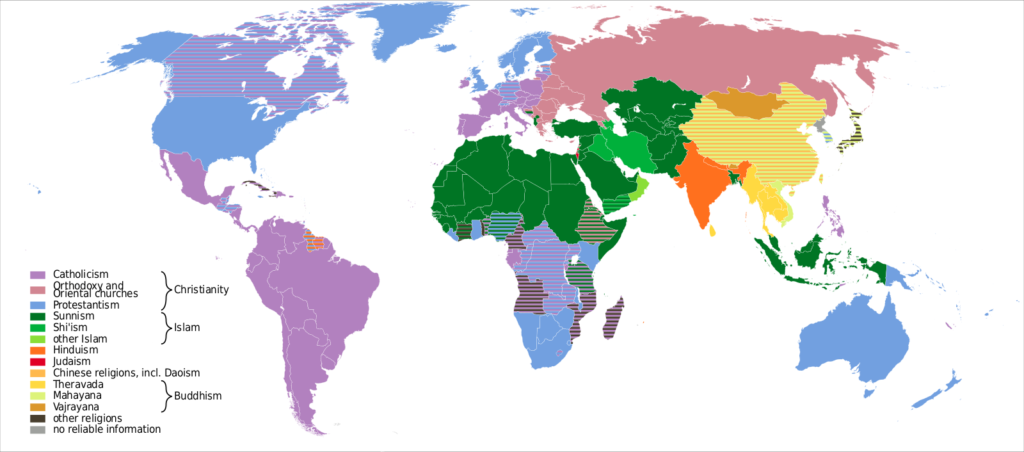

We believe what others around us believe: Many of our most fundamental beliefs, such as about religion and politics, are formed before we’ve had a chance to question them.

Source: de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bild:Weltreligionen.png

The more a belief is aligned with our current worldview the more likely we are to accept it as true: After all, why skeptically question something you already “know” is true?

This tendency to search for and favor information that supports what we already believe, or confirmation bias, is what makes us prone to falling for “fake news.” Before the 2016 election, “fake news” stories, such as the Pope endorsing Donald Trump for president and Hillary Clinton running a pedophile ring in the basement of a pizzeria, were widely shared and believed by many who fell prey to their own biases.

We believe what we hear: Have you heard that Napoleon was short? Well, he wasn’t. At around five feet six inches, he was of average height for a man at the time. But the myth is so pervasive in our culture that it continues to live on. It’s takes more energy to question a claim than it does to accept it, so our lazy brains often take the short-cut and assume it’s true.

The more we hear something, the more likely we are to believe it: The more a claim is repeated the easier it is for our brains to process, regardless of its truth. And even if the repetition is to debunk the misinformation!

Back to fake news. Because of a combination of personal choices in friends and news sources, and algorithms designed to keep us engaged, we can get trapped inside echo chambers, where information is repeated. It’s important to remember that, just because we see a headline or claim multiple times, it doesn’t mean it’s true.

We trust our personal experiences

Before humans evolved language, our senses were the primary way we learned about the world around us. As children, we see and hear before we can communicate. And our senses are relatively reliable. Hopefully our senses of sight and sound warn us about the car speeding towards us, and our senses of smell and taste warn us not to eat the rotten food that might make us sick.

Many of us think that our personal experiences are the best way of knowing something. For example, jurors assume eyewitness testimony is the best kind of evidence. Many believe homeopathy is effective because they’ve tried it and it worked for them. And people may believe in ghosts because they’ve seen one.

The problem is our perceptions are not as accurate as we think they are. Our perceptions are subjective interpretations of reality, and are influenced by our past experiences, expectations, emotions, and biases.

Essentially, perception is not reality. It is the lens through which we filter reality.

Back to the examples. Mistaken eyewitness testimony is the leading cause of wrongful convictions.

There’s literally nothing in homeopathy that would cause a biological response. It’s a placebo. But the placebo effect, feeling better because of expectations, is real.

And as for ghosts: I once stayed overnight in a “haunted” castle on the Rhine River in Germany. I’m not necessarily one who believes in ghosts, but I was certainly on high alert all night. What was that sound? Was that cold air I just felt? What was that in the corner of my eye?

The point is that our beliefs and expectations influence how we perceive reality. We assume that seeing is believing. But actually, believing is seeing.

We’re more likely to believe information from people we trust

Humans are social animals. Our ancestors depended on each other for security, and collectively we can know more than any of us can independently. So trust was – and is – essential to survival. Our personal experiences can only take us so far. Trusting others and their experiences offers us a short-cut about what to accept as true.

We believe authority figures: As children, our very survival depends on our parents and other trusted family members. Why should they listen?“Because I said so!”

For example, parents tell children to not play with knives or eat dog poo, so clearly it’s adaptive to listen to adults. Most also believe in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy for the same reason.

As adults, we continue to trust authority figures, from our religious leaders to politicians.

We believe what members of our “tribe” believe: “Tribes” are any group with shared interests or identities, from nationality, to politics, to religion, to race/ethnicity, and countless others. Our tribes are often a source of pride, and to boost our self-esteem we boost our group’s standing. We want our tribe to “win.” “Truth”, therefore, depends on whether the person making the claim is one of “us” or one of “them.”

As you can see, trusting authority figures and our tribes for knowledge can be problematic. They may be wrong, and yet, disagreeing can cost us our social standing in our group.

For example, after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, Americans coalesced under our shared national identity. Patriotic displays were ubiquitous, as Americans signaled to each other our tribal loyalties. Unfortunately, disagreeing with American foreign policy was labeled as “unpatriotic,” as epitomized by George W. Bush’s infamous line: “You are with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

The problem here isn’t that we trust some sources more than others. The problem is where we are placing our trust. You may love your uncle dearly, or be a proud democrat or republican, but neither are inherently trustworthy sources of all knowledge!

The Take Home Message

Our brains are belief engines. It would take too much time and energy to demand evidence for all of our beliefs, so we instead rely on short-cuts to help us determine what’s true.

Once we’ve formed beliefs, we search for evidence to justify it, often overlooking evidence that doesn’t confirm what we already think is true. And because we feel we’ve arrived at our belief by logically evaluating evidence, we’re less open to changing our minds.

If we want to align our beliefs with the truth, we should first question how we came to the belief in the first place. But we generally don’t think to question our beliefs. We just assume they’re true.

Many of us are surrounded by people who share our beliefs. I confronted some of my own assumptions on a tiny island in the South Pacific, but in today’s connected world one does not need to go nearly that far.

So, let’s get out of our echo chambers and learn what others believe, and give ourselves the opportunity to learn about our own.

Learn More

American Psychological Association, A Reason to Believe

Michael Shermer, The Believing Brain

Psychology Today, Why Do People Believe in God

Smithsonian Magazine, In John They Trust

Scientific American, Why People Believe Invisible Agents Control the World

Thanks to John Cook, Lynnie Bruce, and Anthony Trecek-King for their feedback.

Great essay. One has to understand that the root of the brain’s behavior is its very structure. Ideas and emotions are basically neural networks and generalizations thereof. It requires huge energy to set them up. Once they are up, they are up. THUS one has to be careful what one is exposed to… Or NOT exposed to… Starting as children.

A subtle point of outrageous bias, for example is in the graph of religions above: tiny differences between various Christian sects are blown up with different colors…. Whereas enormous differences between different versions of Islam are ignored, and they are called “Shia”, or “Sunni”. However, in some of the “Sunni” zones, “Sunni” were forbidden to enter… And this by variants of Islam older than “Sunni”. This may look over-subtle… Until one realizes that most “Westerners” identify the belief of an Islamist sect, “Sunnism”, in its Wahhabism extremism, as all of Islam… And that, in turn has huge consequences on democracy, because Wahhabism is antithetical to democracy… Which versions of Islam opposed to Sunnism often are not…

This points to something: bias from sheer ignorance… the most frequent sort of bias…

Pingback: The Person Who Lies To You The Most…. Is You | Climate Change

Overstating the obvious, but thanks!!

son los pensamientos que hacen que sobrepiense