Witchcraft and the Danger in Believing without Evidence

Warning: Disturbing content

When a young boy complained of stomach and chest pains, his family rushed him to the doctor. Tragically, he died a few hours later.

Janet and Andrew, the boy’s mother and uncle, suspected witchcraft. They tracked down two women in the forest, who, under torture, admitted to sorcery, but accused 20 year-old Kepari Leniata of being a witch and killing the child.

Kepari was dragged from her home by a mob, stripped naked, and tortured with white-hot iron rods. After confessing, she was doused in oil, hands and feet bound, thrown onto a pile of trash, and burned alive in front of hundreds of onlookers.

A few years later, another girl, Nancy, fell ill. Rumors again began to circulate….. There was sorcery in the air. They captured six year-old Justice, believing she had stolen the girl’s heart. When they used hot knives to peel away Justice’s skin, Nancy seemed to recover, and when they stopped, Nancy seemed to worsen.

They tortured Justice for five more days, waiting to see what happened to Nancy, ready to execute Justice if Nancy died. Thankfully, Justice was rescued.

Why did the villagers suspect Justice of witchcraft? She was Kepari’s daughter.

Between 1482 and 1782, up to 50,000 people, mostly women, were executed for witchcraft. Witches were blamed for killing crops, bad storms, even birth defects, things we know today have natural, not supernatural, causes. Being accused of witchcraft was often sufficient evidence, as were “witch marks” like moles or birthmarks.

But the best evidence? Confessions. And how do you get a witch to confess? Torture.

From top left: The saw, Great Ripper, Spanish Donkey, Burn at Stake, Spiked Chair, The Rack

I can honestly say I would confess to just about anything under these circumstances. And so did many accused witches. In Germany in the late 16th century, German farmer Peter Stumpp confessed to turning into a werewolf and eating fourteen children and two pregnant women, and midwife Walpurga Hausmännin confessed to vampirism and killing 40 children. Both claimed to have gotten their powers from the devil, and concocted elaborate details of their supposed crimes, likely to escape the horrific torture they endured.

And unfortunately (fortunately?), once you confessed, you were executed, often by being burned alive, but maybe only after being mutilated.

But Kepari Leniata didn’t live in Medieval Europe. Or even 17th century Salem. She was tortured and executed in Papua New Guinea, in 2013.

Purported to be the burning rubbish pile on Warakum Junction Road, in Mount Hagen, Papua New Guinea, on to which 20-year-old Kepari Leniata was thrown in 2013. Photo: AFP. https://www.executedtoday.com/2018/02/06/2013-kepari-leniata-burned-as-a-witch/

And she’s far from alone. Across the world today, from Sub-Saharan Africa to South Central Asia, to the Amazon, belief in witchcraft is prevalent, and hundreds of people, mostly women, are executed each year. Today.

I apologize for traumatizing you with these stories. I admit, I cried and felt sick to my stomach writing this. But I had reasons for doing so.

First, there can be real harm to believing things that are not true. Our beliefs impact our behaviors and actions. For example, those who don’t accept the dangers of COVID-19 are less likely to wear a face mask, and those who believe vaccines are dangerous are less likely to immunize their children. And unfortunately, cancer patients who believe in alternative medicine are more likely to refuse evidence-based treatments, and are more likely to die as a result.

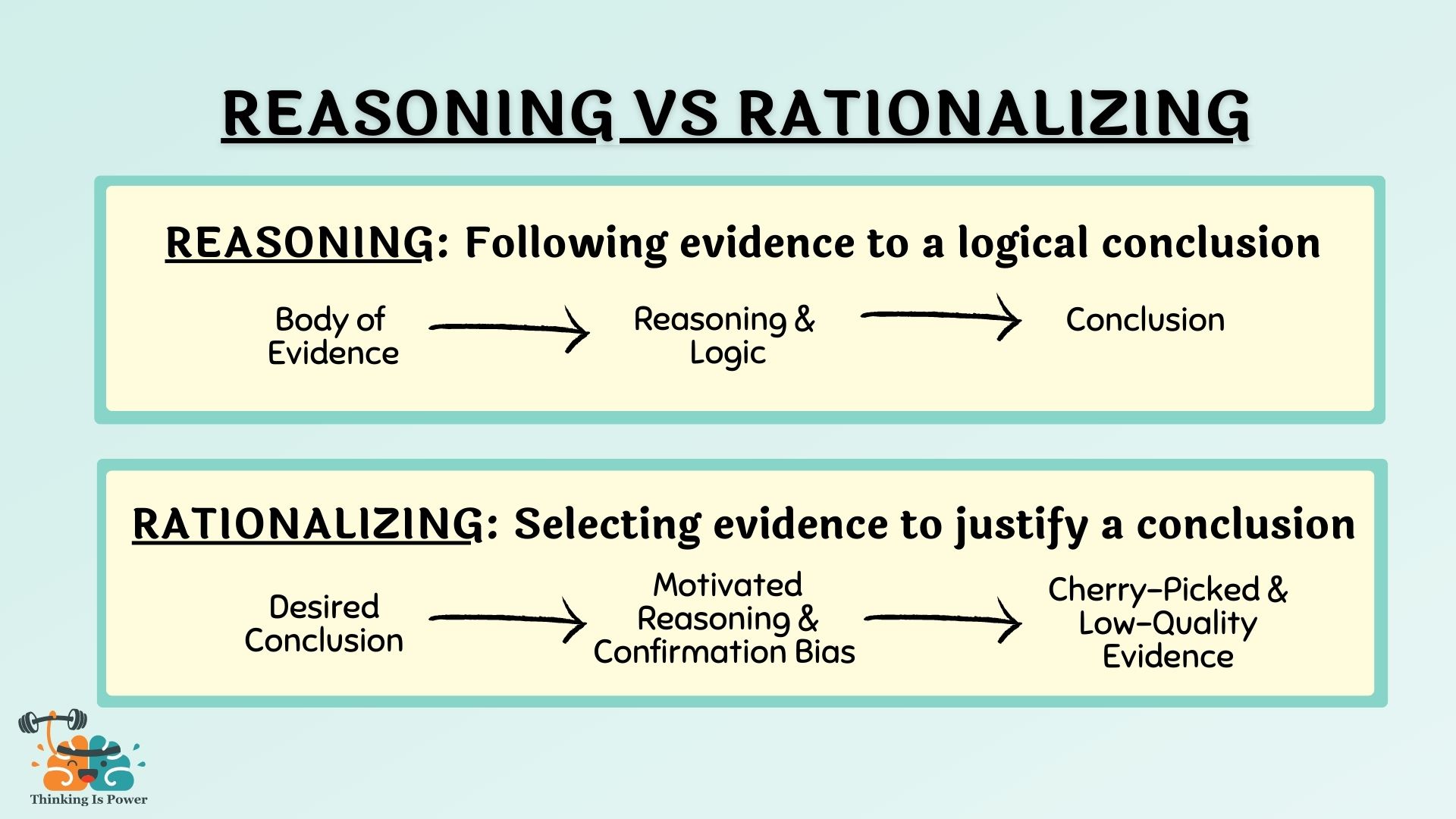

Second, we often aren’t as rational as we think we are. We think we follow evidence to a conclusion. In reality, the opposite is true. We come to our beliefs through irrational ways. We believe what we’re told, especially from trusted authority figures. And we believe what those around us believe. Once we believe, we work backwards to find evidence to rationalize the belief.

And we want explanations, so we search for patterns. We’re so good at finding patterns we even find non-existent ones. Then, we assume there’s an intentional, often supernatural, force behind the pattern.

Janet wanted to know what killed her child. In Papua New Guinea, nearly everyone believes in sorcery, and has for generations, and they see “evidence” everywhere for good and bad magic changing fortunes. Most lack education and proper health care, and even electricity and running water. So when sudden deaths or diseases strike, magic is blamed, and angry mobs find scapegoats for justice.

And third, evidence matters.

Evaluating Evidence

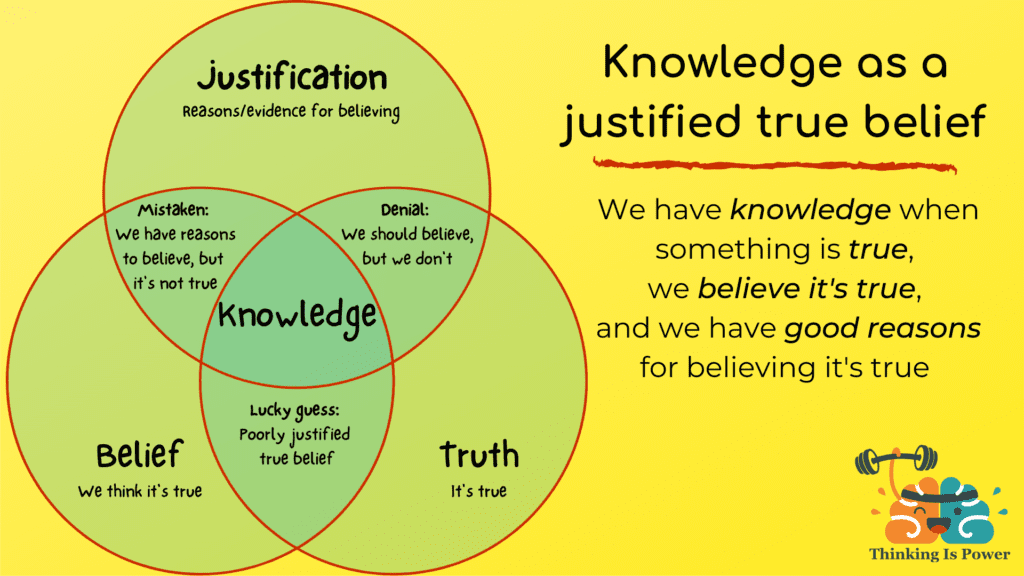

In our search for knowledge, evidence gives us reasons to believe. In general, the more and better the evidence, the more justified we are in accepting that something is true.

While there are many ways to evaluate evidence, four useful criteria are that the evidence should be sufficient, relevant, comprehensive, and reliable.

1. The evidence must be sufficient to establish the truth of a claim.

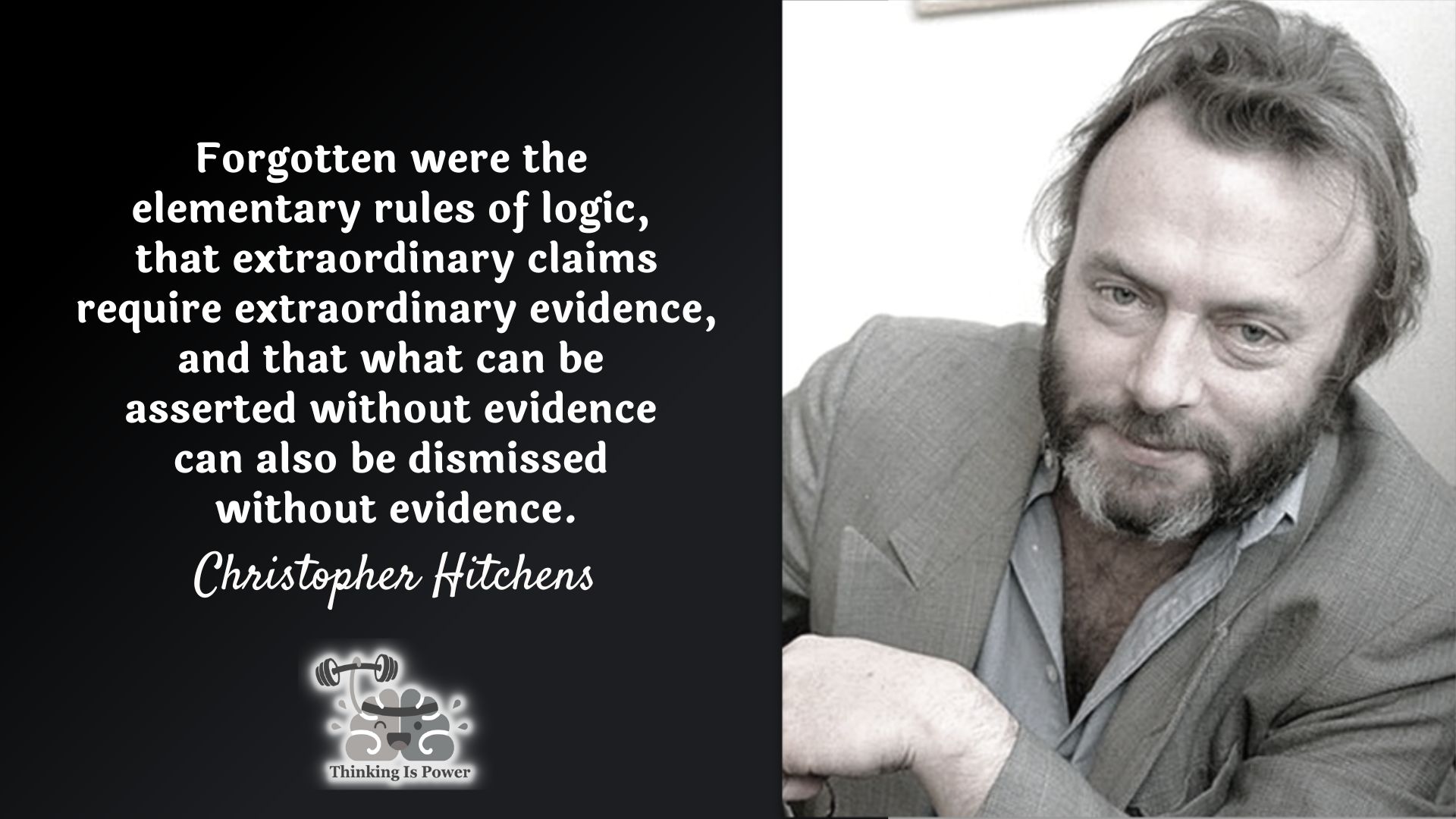

The person making the claim bears the burden of proof, and must provide enough positive evidence to establish a claim’s truth. Claims made without evidence provide no reason to believe, and can be dismissed.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. Essentially, the more implausible or unusual the claim is, the more evidence is required to believe it.

Claims based on authority are never sufficient. Expertise matters, of course, but they should provide evidence. But, “because I said so,” is never enough.

Anecdotes are never sufficient. Personal stories can be very powerful. But they can also be unreliable. People can misperceive their experiences and be wrong. And unfortunately, people can also lie.

As an example, let’s say you own a company, and Jamie works for you. She is an excellent employee, always on time, and always does great work. One day, Jamie is late for work.

If Jamie tells you her car broke down, you most likely will believe her. You have no reason not to, although if you’re really strict you may ask for a receipt from the tow truck driver or mechanic.

But what if Jamie tells you she’s late because she was abducted by aliens? I don’t know about you, but my standard of evidence just shot through the roof. That’s an extraordinary claim, and she bears the burden of proof. If she proceeds to tell you that the aliens look like faceless octopi that communicate telepathically, that one of them took her to another dimension and forced her to bear offspring, but then reversed time to bring her back without physical changes… Again, just speaking for myself, but I’m either going to assume she’s lying, or send her to a medical professional.

2. The evidence must be relevant to the claim.

In an attempt to support a claim, some may, either deliberately or not, use irrelevant evidence. It may sound persuasive, but if the evidence does not support the claim, it’s useless in establishing the claim’s truth.

Examples include logical fallacies of relevance, including:

- Appeals to emotion, such as to fear, anger, pride, or pity, which rely on emotionally charged language to persuade. Strong emotions can be very convincing, but they’re not evidence.

- Ad hominem attacks shift the focus away from the evidence and toward the person making the claim. Your dislike for someone, or their actions, is irrelevant to the truth of a claim.

- Appeal to the masses, which suggest that, since everyone believes something, it must be true, or appeal to tradition, which asserts that the claim must be true because people have believed it for a long time. Again, this is not evidence. People can be wrong. For a long time.

- Red herring, which occurs when someone shifts the focus away from the topic being discussed.

For example, your son failed his science exam because he spent most of the last three weeks of class playing Angry Birds on his phone. When you ask him why he failed, he says: “I know I did poorly, but have I told you lately how much I love you? That teacher is a jerk and he really hates me. Everyone in the class did poorly. Besides, I did all of my chores this week.”

This may sound persuasive, but none of it was relevant to why he actually failed his exam.

3. The evidence must be comprehensive.

Imagine all of the evidence for a claim is like a puzzle. If we stand back and look at the whole puzzle, we can see how the pieces fit together and the larger picture they create. This is called the body of evidence.

You could, either accidentally or purposefully, cherry pick any one piece of the puzzle, and miss the bigger picture.

For example, everything that’s alive needs liquid water. Water is so essential to life that, when looking for possible life outside of Earth, we look for evidence of water. The typical person can only live for three or four days without water.

But what if I told you that all serial killers have admitted to drinking water? Or that water is used in certain forms of torture? Or that it’s the primary ingredient in many toxic pesticides? Or that drinking too much water can cause the brain to swell and be fatal?

By selectively choosing pieces of evidence, we can wind up with a distorted view of reality. But if we want to better understand reality, it behooves us to look at all of the evidence.

4. The evidence must be reliable.

Evidence is essentially information that’s used to determine if something is true. However, not all information is created equal. To determine if evidence is reliable we must look at two factors.

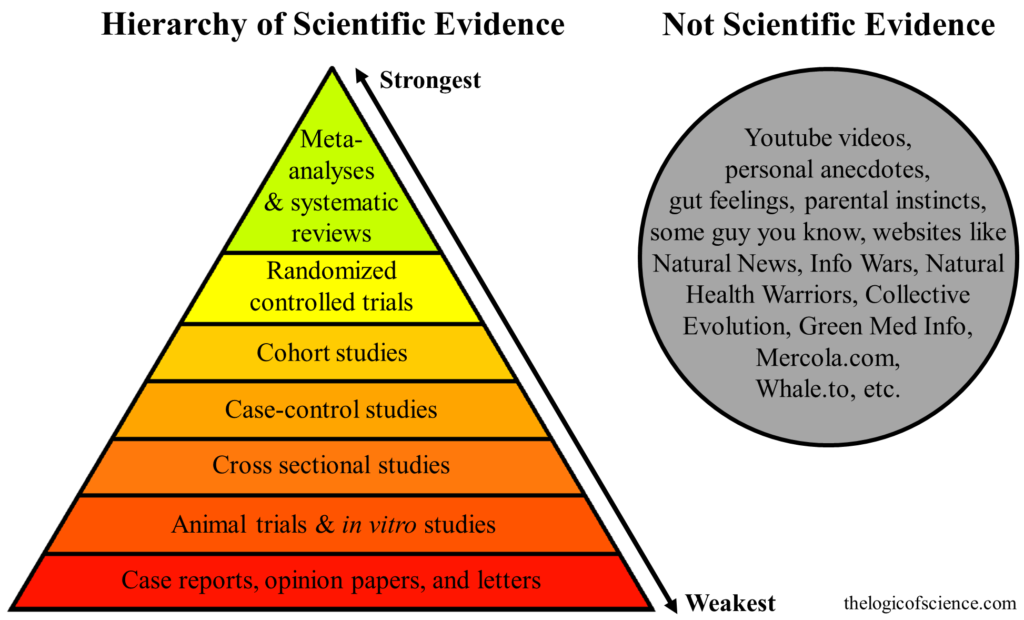

How was the information gathered? A major reason science is so reliable is that it’s a system of collecting and evaluating evidence. (It’s also why people often use “science” or “studies” to give legitimacy to their beliefs.) However, even scientific studies vary in the quality of evidence they provide.

For example, studies in lab animals or test tubes provide the lowest form of evidence; uncontrolled observational studies are better, but provide correlational evidence; and randomized controlled trials provide excellent causational evidence. Because meta-analyses and systematic reviews look at the big picture, they provide the best type of evidence.

What is the source of the information? Sources really matter. We are drowning in information these days, and not all of it is reliable.

In general, the most reliable sources are peer-reviewed journals, because like the name suggests, the information had to be approved by other experts before being published. Next most reliable would be the high-quality journalistic outlets that have a track record of accurate reporting.

The least reliable sources are personal stories, because people can misinterpret their experiences. (They can also lie.) And it’s important to keep in mind that anyone can create YouTube videos, FaceBook memes, Twitter threads, or even blogs.

(Learn more: Don’t be fooled… Fact Check!)

The unfortunate case of Kepari and Justice

Let’s circle back to Kepari and her daughter.

Janet claimed that Kepari used witchcraft to kill her child. Janet’s reasons, or evidence, included the fact that she lived next door, her child died, and two women accused Kepari of witchcraft under torture.

Janet bears the burden of proof for this claim, and the claim of witchcraft is an extraordinary claim, as there is no scientific evidence for the existence of sorcery. In addition, confessions from torture are not reliable. Many of the accused witches throughout history have concocted wild, intricate stories, from flying through the air to wild orgies with the devil. Anecdotes are insufficient evidence for a reason, and these stories are almost certainly stories told to escape excruciating torture.

In addition, the fact that Kepari lived next door is simply a correlation, and not sufficient evidence to demonstrate that Kepari committed murder. The same is true for Justice, whose crime was being the daughter of another supposed witch.

The take–home message

This unfortunate story is a reminder that we aren’t as rational as we think we are. Many of our beliefs are influenced by our culture and geography, and not the result of evidence-based thinking. Belief in witchcraft is less common in wealthy countries, but there’s a good chance that you have beliefs that are just as irrational.

Demanding evidence is foundational to critical thinking, whether it’s evaluating claims of others or our own beliefs. But no one can fool us as much as we can fool ourselves, and if we’re looking for evidence, we will find it.

So ask yourself: What is the source of this belief?

Then, evaluate the evidence: Is it sufficient? Is it relevant? Is it comprehensive? And is it reliable?

If we want to align our beliefs with the truth, it’s essential that we question ALL of our beliefs. If it’s true, if it will survive being questioned.

And importantly, if the evidence suggests we’re wrong, we should be open to changing our minds.

To Learn More

Los Angeles Times, Murder Charges Filed after Woman Burned Alive in Papua New Guinea

Post Magazine, In Papua New Guinea, Witch Hunts, Torture, and Murder Are Reactions to the Modern World

Thanks to John Cook, Lynnie Bruce, and Anthony Trecek-King for their feedback.

Pingback: Why trying to prove yourself wrong is the key to being right | Climate Change

Pingback: Thinking is Power: Are you a Critical Thinker? | Climate Change

Wow this was very well written I absolutely loved the article and the creative visuals! God bless :D. Curious do you there to be compelling evidence God exists? And if so is Jesus Christ God? For me I believe I’ve found it but I totally agree with you we must challenge every belief and if its true it will survive!

Thanks for the kind words and comment!

To answer your question: God(s) is(are) an example of an unfalsifiable belief. It might be true, but we can’t test it with evidence. This article may help: https://thinkingispower.com/why-trying-to-prove-yourself-wrong-is-the-key-to-being-right/

Cheers

Melanie

Your conclusion that supernatural belief can’t be “tested” with evidence is contradicted by your own article on falsifiability/unfalsifiability. You state that, “Supernatural claims can be falsifiable under certain conditions.” For instance, the claims of Christianity could be falsified if we found Jesus’ remains. Evidence is vitally important in evaluating a faith claim’s truthfulness–falsifiability is not necessarily crucial. In the philosophy of religion there is the concept of “inference to the best explanation,” which includes the criteria of explanatory scope and power, logical consistency, coherence, less ad hoc, integration with other fields of knowledge, and existential livability. These criteria are very useful in evaluating among and within supernatural belief systems and for evaluating individual beliefs. I have used these to evaluate various religions and also doctrines within Christianity. Beyond that, on a more personal level, Pascal noted that the biblical God has purposely given sufficient but NOT overwhelming evidence for his existence because he wants his creatures to choose belief–he woos, he does not coerce. He’s looking for a love response. Overwhelming evidence would make it impossible to disbelieve. Pascal says, “he has qualified our knowledge of him by giving signs which can be seen by those who seek him and not by those who do not. There is enough light for those who desire to see, and enough darkness for those of a contrary disposition.” (Pensee 149).

Thanks for the comment!

Supernatural claims are by definition above and beyond what is natural, and therefore aren’t observable and testable. For example, if I claimed I cast a spell that caused a car accident, there’s no way to use evidence to disprove me. However, the car accident itself is an objective event, and is therefore falsifiable. It would behoove us to search for falsifiable causes — eg. Driving under the influence, texting while driving, spilling hot coffee and looking down for a moment — and try to rule out what we can to arrive at the most reasonable cause of the accident.

Knowing the difference between claims that can be falsified from those that can’t is central to thinking critically. Unfalsifiable claims aren’t by definition wrong, they’re just not able to be objectively tested with evidence…no matter how much “evidence” we find to try and support them.

Thanks again.

Melanie

So, Melanie, I would assume there are unfalsifiable beliefs you hold, which you have arrived at because there was a sufficient quantity and quality of evidence to support them?

Hi Mike,

Just to be clear (because I worry my comments aren’t coming across as intended), there is no judgement. I’m not trying to say we shouldn’t hold any unfalsifiable beliefs, but that it’s important to understand the difference and not try to use evidence to support a belief that’s inherently not evidence-based.

Additionally, annother important aspect of critical thinking is scaling our acceptance of a belief to the evidence. I think of a 1–100% scale where I try to avoid the extremes and adjust my confidence as necessary.

As for my beliefs: I do hold unfalsifiable beliefs, as opinions and values are subjective. And I’m sure I hold others that I’m not currently aware of. But I think you’re specifically talking about supernatural beliefs, in which case no, I don’t believe I do. I don’t think they’re impossible, but without evidence (and importantly the ability to test them against evidence) I have no reason to accept them. That’s my personal choice, and you may choose a different path. I’m only here to help those interested in learning about critical thinking.

I wrote this epistemology exercise to help my students evaluate their beliefs. In case you’re interested: https://thinkingispower.com/the-power-of-questioning-our-beliefs/

Thanks

Melanie

Pingback: Skepticizam kao zaštita od obmane: Priča o duhovima iz stvarnog života - FakeNews Tragač

Melanie, thank you for your reply. I read your epistemology exercise and agree with it as a good way to achieve knowledge. It is exactly what I suggested through the well-established process called “inference to the best explanation.” Critical thinking is exactly the process I used to arrive at my Christian faith. I sense that the reason you have come to a different conclusion about anything supernatural is that you dismiss the whole area as “unreal.” Epistemologically you dismiss it as a source of knowledge and truth. I have never found a sound justification for that. There are many things in life that are above and beyond the scope of science and they can be true and be known. However, by observing the content of your website and the resource page, it seems you have limited critical thinking to things that are only “natural.” Naturalism isn’t a scientific conclusion, it’s philosophical and it doesn’t seem to promote human flourishing–just look at the works of the existentialists–very depressing. Some of your resources are also decidedly ANTI-supernatural. Why is that? I think you would better serve your readers if you acknowledged the limits of science, otherwise you fall liable to the claim of “scientism,” a very untenable position (see Nigel Brush’s “The Limitations of Scientific Truth”). I would suggest several resources that might help. Francis Schaeffer, in his book “Escape from Reason” describes the origins of the fact-value split in science, art, and philosophy and critiques it. Nancy Pearcey’s “Total Truth” and “Finding Truth” offer further value.

Let me try to clarify my position: It’s important to know if a claim or belief is falsifiable or unfalsifiable. If it’s unfalsifiable, it can’t be proven wrong and therefore isn’t testable with evidence.

Scientific claims should be falsifiable, something I’ve written about many times. If you’re interested, I’ve also written about the limitations of science, such as here:

https://thinkingispower.com/science-what-it-is-how-it-works-and-why-it-matters/

Science has reached a point where unfalsifiable are possible. Such as the mulitverse. I read an article stating it is dangerous to drop the idea of falsifiable claims but in many cases it may prove to be a hindrance. Are we between a rock and a hard place?

Hi Larry,

Geez, you could’ve given me an easier question!

Seriously, though. I’m going to punt on part of it, because I don’t have the required expertise in physics to have a valuable opinion. And on the rest of it, I’m going to say “it depends.” Not all science is an attempt to falsify claims, but scientific claims have to be empirical and measurable, and therefore falsifiable.

Hope the helps! Thanks for the comment.

Melanie

I understand your position, so clarity is not an issue. However, you really didn’t respond to any of my content, which is disappointing. I’ll conclude with this: There are MANY areas of life where scientifically observing the natural world can’t provide any answers, but that doesn’t mean that evidence and critical thinking can’t be used to find a good answer in non-“natural” areas of life. Your “Science–What it is” article really isn’t clear about these limitations. I can think of several: Can it tell us what love is? Can it tell us why relationships are important? Can it tell us if there is such a thing as morality–right and wrong? Can it tell us if there is a purpose to life? Can it tell us what we should value? Can it tell us if there a supreme being or not? The answer is no. But critical thinking, the laws of logic, avoiding informal fallacies, proper interpretive methods, etc. can be used in many non-“natural” areas, even in theology. I use them all the time, and when I read bad theology, I critique it with these kinds of tools. Consequently, I would then disagree with your third assumption of science–you limit it to natural processes–it can be applied to much beyond that.

Out of necessity, my responses thus far have largely been limited to clarifying my position. I’m trying to give you the benefit of the doubt and assume the reason you keep misrepresenting my comments and writing is because I haven’t been clear enough for you to understand. I’m happy to continue to engage with you, but only if you extend me similar curtesies.

Along those lines, I’m confused about your position. Do you want science to attempt to prove the existence of supernatural beings? Or do you want science to limit itself to things that can be observed?

To be clear: I am NOT anti-supernatural. I AM saying it’s not science.

Let’s circle back to the hypothetical car accident, for which I gave several examples of falsifiable (and therefore testable) hypotheses. Now imagine someone claiming their grandmother’s ghost told them to steer into traffic. Or that the driver was cursed by a witch’s spell. Or that god was punishing them for their previous misdeeds. It is possible for any of those things to be true, although highly unlikely as we haven’t established the existence of ghosts, gods, or supernatural curses. The point here is that none of these claims are falsifiable. There’s no way to test any of them against evidence, to rule any out, or to attempt to determine which is most likely to be true. And that’s a good thing: if we assumed any of these explanations were true, we wouldn’t search for or test any falsifiable explanations and therefore not be able to figure out most likely cause of the crash.

Hope this helps. Thanks for your comment.

MTK

Melanie,

I surely have not intended to misrepresent you in any way, so I am open to evidence I have done so. . . . Further, to answer your questions about my position–the first about “Do I want science to prove the existence of supernatural beings? Obviously that is not possible directly, since by definition a spiritual being does not possess a physical body–it can not be empirically observed. But there is loads of evidence that plausibly lead one to that conclusion. Consider the content of the intelligent design program. Considering the conservation laws–there is no physical explanation for the existence of matter/energy or what exploded in the big bang. And, yes, I want science to limit itself to what can be observed–the intelligent design movement looks at evidence from physics, chemistry, and biology. History and archeology are sciences, and claims from various religions can be scrutinized. In fact, Christianity is the one religion in which these two sciences can say the most–it opens itself to empirical investigation because it makes claims about historical events, places, and people. Can’t say the same for others.

I just read an article about falsifiability and faith, and I reference it here for your reading and comment:

https://capturingchristianity.com/is-belief-in-god-falsifiable.

Sincerely,

Mike C.

Hi Mike,

Thanks for the clarification. And thanks for sending the article — it was helpful for me to see where you might be coming from.

I think this section from the article nicely illustrates the crux of the issue:

“Premise 1: Science is falsifiable.

Premise 2: Theism is not falsifiable.

Conclusion 1: Theism is not science.

Premise 3: If something is not science, it is not rational to believe.

Conclusion 2: Theism is not rational to believe.”

It is true that the supernatural is not falsifiable, and if it’s not falsifiable, it’s not science. It does not follow, though, that if something isn’t science it isn’t rational to believe. Values, ethics, attitudes, etc aren’t falsifiable, but that doesn’t make it irrational to hold values.

Stephen Jay Gould explained the separation between science and religion with a concept he called “Non-Overlapping Magisterium” (NOMA): both look at the same world but through different lenses, and neither should intrude on the purview of the other. Science cannot falsify the existence of a god, of any kind, and therefore should not claim to use the tools of science to prove that there is no god. This also means that religion cannot claim to use the tools of science to try to prove there is a god.

Which brings me to intelligent design. As a biologist, I can tell you that evolutionary theory is the single most supported and useful theory in all of the life sciences. It explains the unity and diversity of life. Nothing in biology makes sense without evolution. Conversely, ID isn’t supported. It doesn’t produce useful hypothesis. And its central premise, an intelligent designer, is unfalsifiable.

But: One can accept evolutionary theory and still believe in god. NOMA.:)

If you’d like resources about evolution (from a Christian’s perspective) or science in general, please let me know. It was nice chatting with you.

Melanie

Two good sources for you to read/watch:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/article/falsifiability/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FDSpLBNQk5I

There are philosophical discussions around the nature of falsifiability, but it doesn’t negate falsifiability as a cornerstone of science.

Intelligent design is not science, because it’s not falsifiable. Evolution is, and it’s withstood 160 years of attempts to falsify it. That’s why evolution is the most important theory in all of the life sciences.

“Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” Theodosius Dobzhansky

Thanks for the comment

Melanie

Pingback: How Skepticism Can Protect You From Being Fooled – “In a world of propoganda, the truth is always a conspiracy.”

Pingback: 6 KEY QUESTIONS TO FIND OUT IF YOUR BELIEF IS TRUE

By making a distinction between “regular” claims and supernatural ones you, quite disappointingly, don’t abide by your own rules. If you followed your rules, you would have to classify a supernatural claim (such as the existence of a god) as extraordinary and thus require extraordinary evidence.

The end of the article states the following: “Janet bears the burden of proof for this claim, and the claim of witchcraft is an extraordinary claim, as there is no scientific evidence for the existence of sorcery.”