The difference between falsifiable and unfalsifiable beliefs

Tony Green was convinced that the threat of the virus was being overblown… it was no worse than the flu. It was a scamdemic.

As a gay conservative, he was used to fighting for respect, but staying true to his values was important to him. He voted for Donald Trump in 2016, and thought the pandemic was a hoax created by the mainstream media and the Democrats to crash the economy and destroy Trump’s chances at re-election. A self-described “hard-ass,” he stood up for his “God-given rights,” and made fun of people for wearing masks and social distancing. He liked his freedom, and he didn’t want the government telling him what to do.

So when the lockdown restrictions lifted, he organized a weekend getaway with his family. It was summer and they hadn’t seen each other in months. It was time to enjoy life.

On Saturday, June 13, he and his partner hosted both sets of their parents at their home. On Sunday, he woke up sick. And by Monday, his partner and his parents were sick. Also on Monday, his in-laws traveled to witness the birth of their first grandchild. Later that night his father-in law was sick….then his mother-in-law…. and their daughter…

And on it went.

The two different types of beliefs

Our minds hold a hodgepodge of beliefs. And while they may feel the same, in terms of how true we think they are, knowing how they’re different can help us think better…and better understand others.

The question is, how would we know if our beliefs are true?

Source: Is a claim true? Use these four criteria to evaluate the evidence

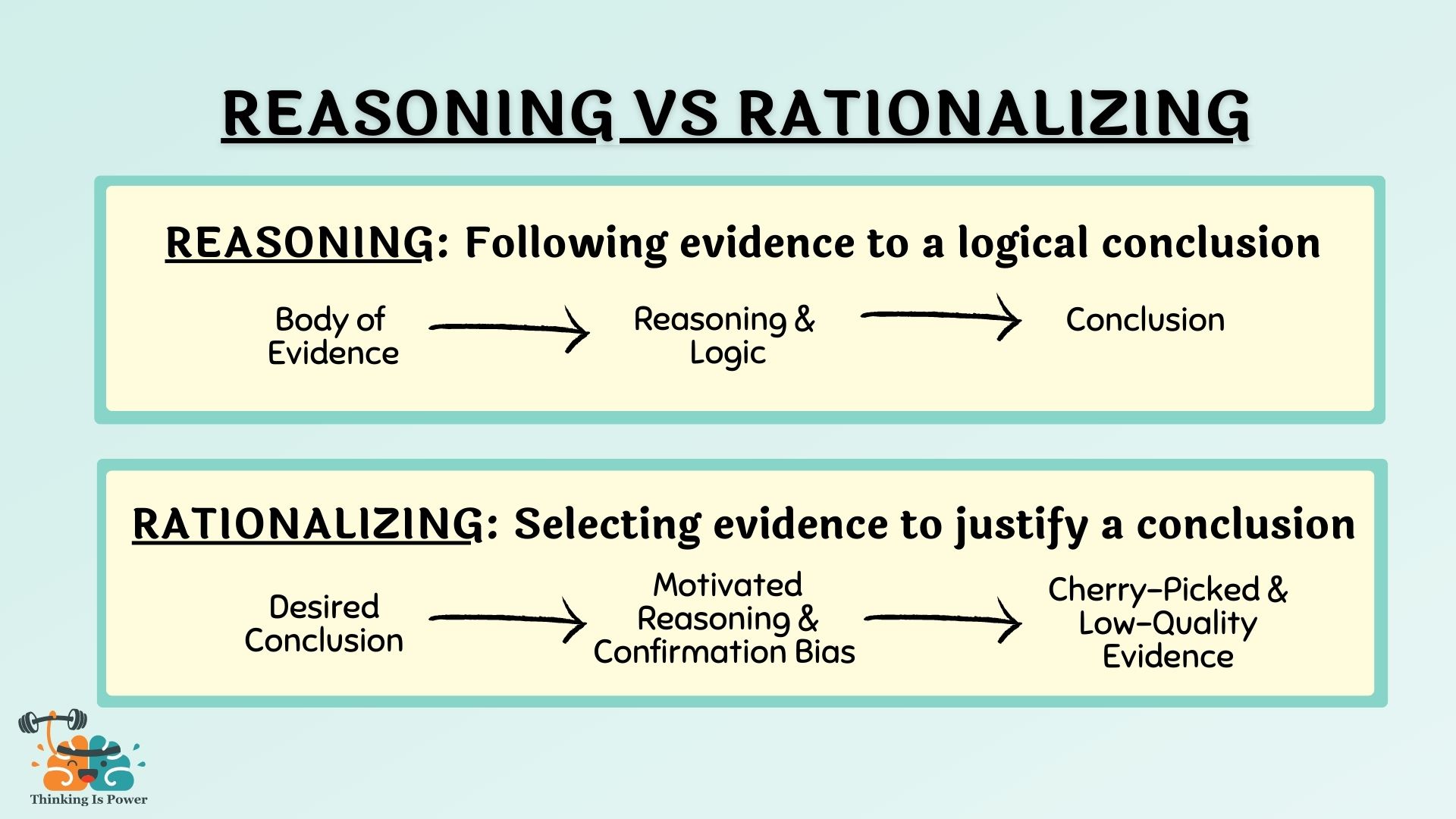

We tend to think our beliefs were formed by logically following evidence to a conclusion, and therefore we have good reasons for believing. However, most of our beliefs are formed in irrational ways. Once our beliefs are formed, confirmation bias kicks in, and we search for and interpret all “evidence” to support the belief.

So it might sound paradoxical, but the secret to finding out if what we believe is true is to try to prove it wrong. And to prove a belief wrong, one needs evidence.

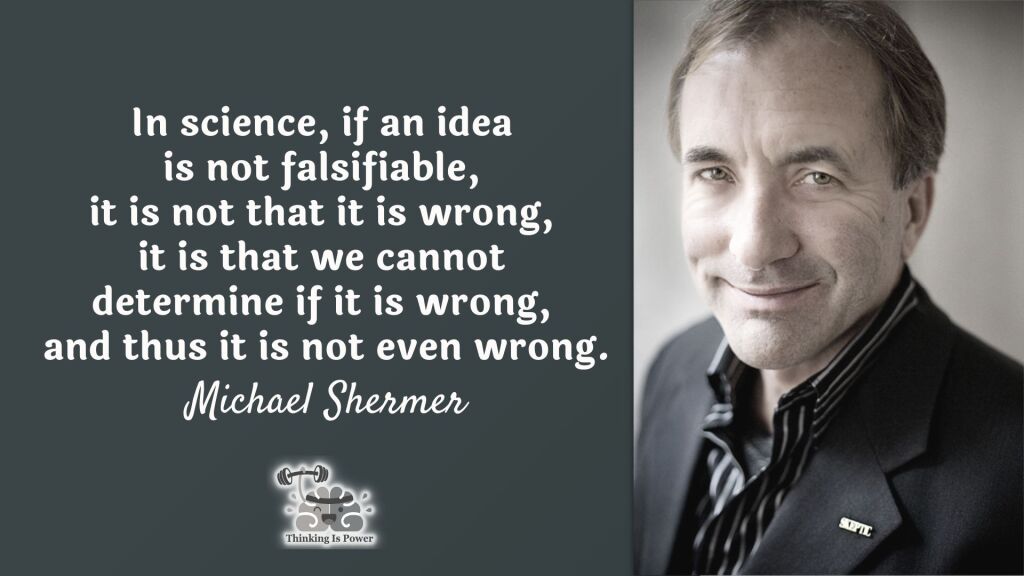

The key distinction that separates the different types of beliefs is that some can be proven wrong, and some can’t.

Falsifiable beliefs are able to be proven false. Essentially, it must be possible to think of an observation that would disprove the belief. If the belief is false, the evidence will prove it false. If the belief is true, the evidence won’t prove it false. It won’t prove it true, either….There’s always the chance that we’re wrong. But if the belief has successfully resisted repeated attempts to disprove it, we’re justified in tentatively accepting it.

When evidence has falsified a belief, it is known to be false. But a false belief must have been falsifiable, or the evidence would not have been able to disprove it.

For example, the belief that homeopathy can treat various health conditions is falsifiable. Countless experiments have shown that homeopathy is no more effective than a placebo. Thus belief in homeopathy is a false belief.

Unfalsifiable beliefs are impossible to disprove, and therefore cannot be shown to be either true or false. They might be either, but we’ll never know for sure. Supporting unfalsifiable beliefs with “evidence” is therefore meaningless, because the claim is invulnerable to evidence.

If nothing could ever disprove a belief, evidence has lost all value. The conclusion is already known. This doesn’t mean it’s true, of course. Just that the belief will remain intact regardless of the evidence.

For example, I have epic, Grade A, gold medal-winning technology problems. I sometimes joke that I’ve been cursed by a Computer Fairy, who sprinkles magic e-Goo on my electronic devices to mess with me. Just because you can’t prove me wrong doesn’t mean it’s true.

The difference then boils down to this: Is it possible to think of evidence that would disprove the belief?

There are four types of beliefs that are unfalsifiable

- Subjective beliefs: Personal preferences, opinions, values, ethics, morals, feelings, and judgements.

For example, I believe that The Princess Bride is the best movie ever made, and that Vegemite is disgusting.

I’m right on both accounts. Prove me wrong!

While subjective beliefs cannot be proved false, we often use facts to justify them.

For example, I believe that cats make the best pets. Cats are quiet. They’re self-cleaning. They poo and pee in a litter box, so they don’t wake you up early in the morning to go for a walk. They are independent enough that you can leave them for a day or two. In short, they’re perfect pets for those not responsible enough for a dog. (Or a child.)

I also believe that healthcare is a basic human right, and that humans have an ethical obligation to save species from going extinct.

But opinions and values aren’t facts.

Many of our most deeply held beliefs are subjective, and therefore unfalsifiable. But we so desperately want them to be true that we may go to great lengths to support the belief with facts and “evidence,” especially in arguments with those who disagree with us. However, if we actually want to have productive conversations, we need to understand the nature of the disagreement. Quite possibly the disagreement is over values, in which case, facts are meaningless.

- Supernatural beliefs: Entities such as gods and spirits, or magical human abilities such as psychic powers.

It’s human nature to try and make sense of events in our lives, and we often seek out a variety of explanations, both natural and supernatural.

By definition, supernatural causes are above and beyond what is natural. Therefore, they are not observable, and thus not falsifiable. This doesn’t mean these claims are true or false, but that there is no way to use evidence to test them.

For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has an obvious natural cause: a coronavirus. But that hasn’t stopped some from claiming the virus was punishment from god for premarital sex, homosexuality, abortion, or generic sinning, and nearly two-thirds of Americans believe the pandemic is a message from god. What that message is, of course, varies greatly depending on whom you ask.

There are some who truly believe the virus is divine judgment. But there’s no way to test divine judgement. And it’s logically impossible for all of the contrasting beliefs of god’s role in the pandemic to be true.

Supernatural claims can be falsifiable under certain conditions. First, if a psychic claims to be able to impact the natural world in some way, such as moving/bending objects or reading minds, we can test their abilities under controlled conditions. And second, claims of supernatural events that leave physical evidence can be tested. For example, young earth creationists claim that the Grand Canyon was formed during Noah’s flood, approximately 4,000 years ago. A global flood would leave behind geological evidence, which we should also see in the Grand Canyon. Unsurprisingly, the evidence disproves this claim. However, even if the evidence pointed to a global flood only a few thousand years ago, we still couldn’t falsify god as the cause.

- Vague beliefs: Undefined, indefinite, or unclear.

Your horoscope for today says, “Today is a good day to dream. Avoid making any important decisions. The energy of the day might bring new people into your life. You’ve achieved a lot recently, so try to celebrate!”

If you spent your day looking for evidence to support your horoscope, you would probably find it. But it’s impossible to disprove, because it didn’t make any measurable predictions.

Or, consider your cranky uncle, who believes that, “Democrats are socialists who hate America and want to take away our freedoms!”

His beliefs almost certainly feel true to him, and if asked, he would probably be able to offer up “evidence.” Yet terms such as socialist, hate, and freedom are loaded words, which lack firm definitions but provoke strong emotions and are able to persuade without evidence.

Interestingly, people often hold extreme views about complex issues that they know very little about. They feel like they understand, but when asked to for greater detail about their beliefs the house of cards collapses.

If you can’t think of a way to observe and measure the evidence, or you honestly question your belief and discover you don’t know many details, there’s a good chance the belief is unfalsifiable. So probe your beliefs…. really question them. How much do you really know?

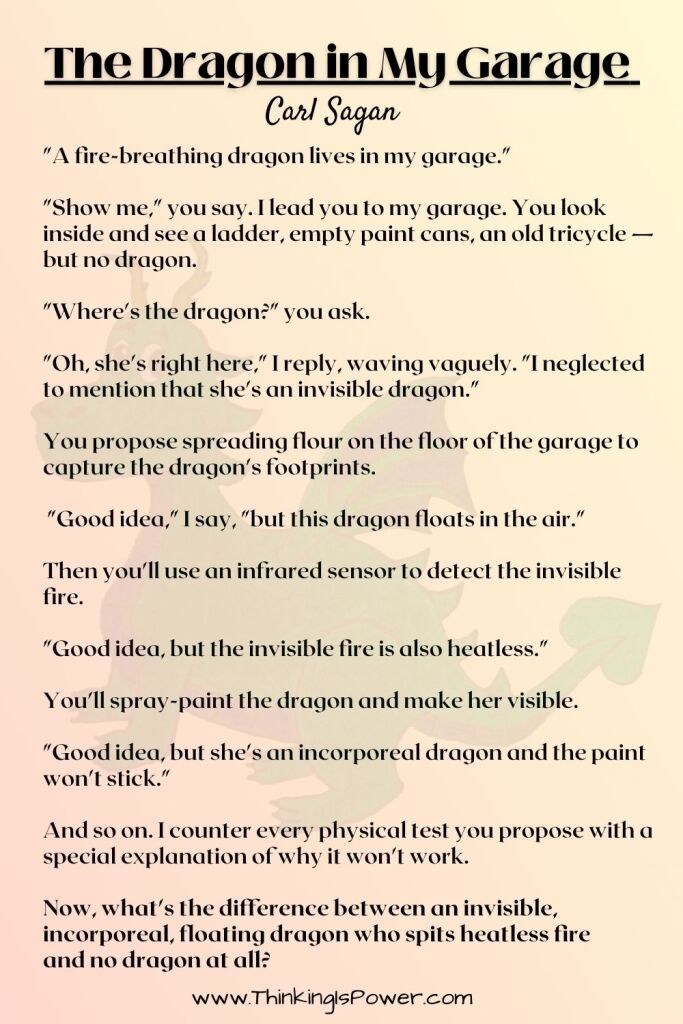

- Ad hoc excuses: Rationalizing and making excuses to explain away observations that might disprove the belief.

While the three types of beliefs described above are inherently unfalsifiable, sometimes we protect false beliefs by finding ways to make them unfalsifiable.

In The Demon-Haunted World, Carl Sagan explained this type of reasoning perfectly:

- Sagan concludes with: “If there’s no way to disprove my contention, no conceivable experiment that would count against it, what does it mean to say that my dragon exists? Your inability to invalidate my hypothesis is not at all the same thing as proving it true. Claims that cannot be tested, assertions immune to disproof are veridically worthless, whatever value they may have in inspiring us or in exciting our sense of wonder. What I’m asking you to do comes down to believing, in the absence of evidence, on my say-so.“

You may have heard the saying, “Facts don’t care about your feelings.” While true, it’s also true that, “Our feelings don’t care about facts.”

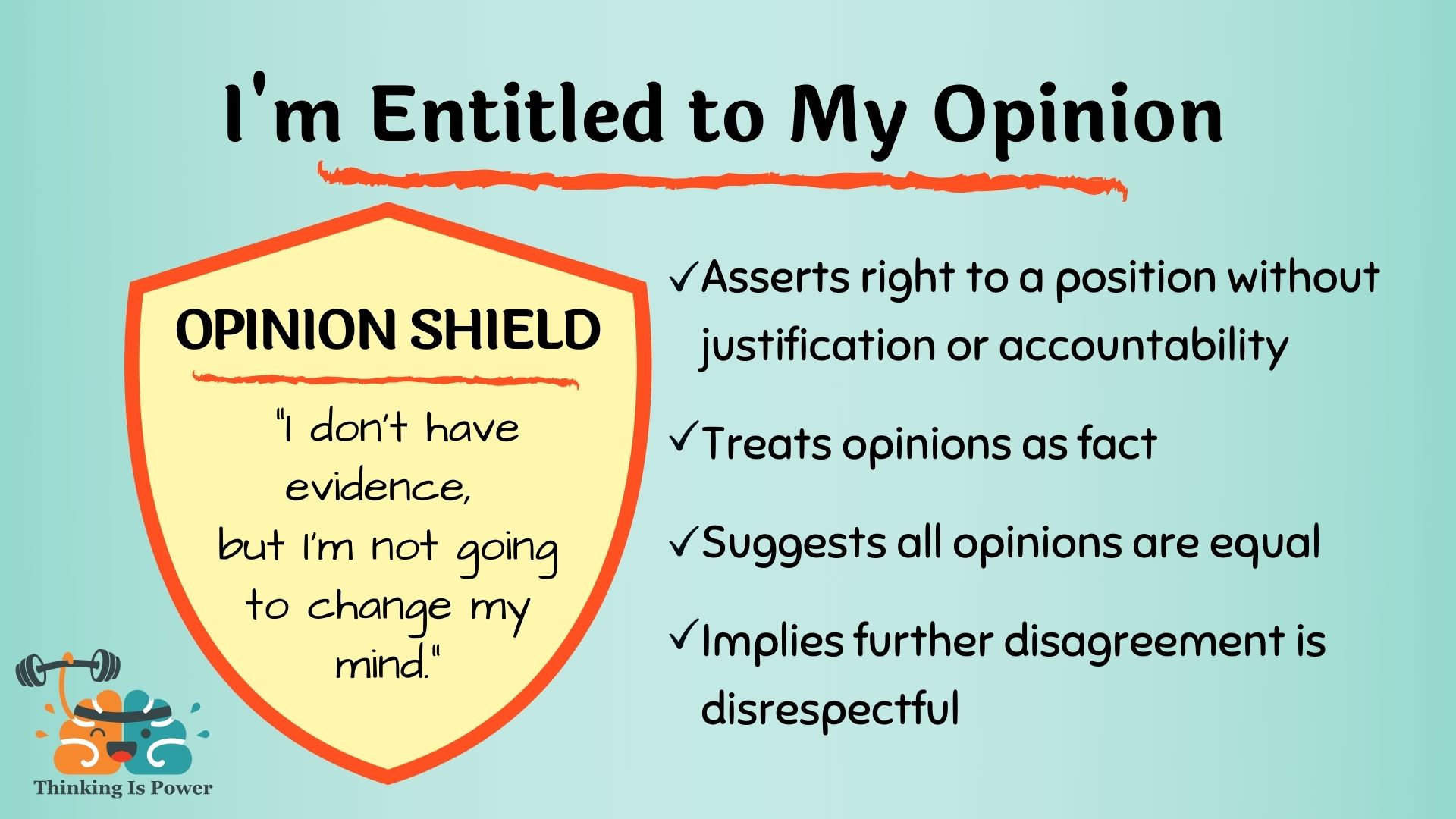

- In the face of facts that contradict a belief, especially one central to our identity or moral values, we use motivated reasoning to reduce the cognitive dissonance that arises when reality and our beliefs are in conflict. When that fails, our Get Out of Jail Free Card is to defend the belief by rendering it unfalsifiable and therefore immune to evidence. We move the goalposts. Discount sources or deny evidence. Proclaim that it’s our opinion.

Ad hoc reasoning helps us find excuses to make the belief unfalsifiable, and therefore unable to be proven wrong. It turns out unfalsifiability may be a psychological advantage, as it feels good to know that no one can prove us wrong.

The tragic tale of Tony Green

After about a week, Green was feeling better. He certainly hadn’t felt well, but it wasn’t that bad.

Then one day he couldn’t breathe, and he passed out. When he woke up, he was in the ER surrounded by a team of doctors. The virus had attacked his nervous system and he nearly had a massive stroke.

He laid in the hospital bed for days, engulfed in guilt and shame. He had paid for his mistake.

Or thought he did.

In the end, the virus infected 14 family members and killed two, including his beloved father-in-law, who died alone in his hospital room. Heartbreakingly, his father-in-law’s mother died nearly at the same time, in the room next door.

Green felt like a drunk driver that had killed his family.

But he hadn’t believed the virus was real. He had listened to those who downplayed the threat. And, he had heard what he wanted to hear.

While extreme, Green’s story is all too human. While the coronavirus is falsifiable, Green denied the rising cases and death rates using ad hoc reasoning to protect what he wanted to believe. And he didn’t like what he perceived as an infringement on his personal freedoms.

Tony Green paid a heavy price for protecting a false belief with unfalsifiable conspiracies and subjective opinions. But in the end, the evidence was too overwhelming, and he was forced to face reality. Unfortunately, it took being hospitalized and losing loved ones.

The take-home message

If you want to know if a belief is true, one of the most important first steps is to determine if it’s falsifiable. All beliefs aren’t the same, and yet it can feel like they are. Belief in god, many conspiracy theories, or strongly held political opinions cannot be proven wrong, no matter how many “facts” you find to support them. If you choose to accept them anyway, recognize that the belief is faith-based, not evidence-based.

Science is effective because it’s constantly testing its theories against reality. It welcomes attempts at falsification. The great Richard Feynman once said, “We are trying to prove ourselves wrong as quickly as possible, because only in that way can we find progress.” Scientific explanations, such as human-caused climate change or evolution or the safety of GMOs are falsifiable, and the fact that they haven’t been proven wrong means they are very likely true.

So the question posed earlier, how would we know if my belief is true, is actually the wrong question to ask. The better question is: What would it take to prove my belief wrong? Then keep in mind the following:

- Don’t just look for evidence that you’re right, because you’ll almost certainly find it if you’re looking hard enough.

- Instead, determine if the belief is falsifiable. If it is, actively look for evidence to prove yourself wrong.

- If the belief is true, it will withstand scrutiny.

- If the belief is not true, the evidence will disprove it. Try to accept the evidence and change your mind.

But remember, if nothing will change your mind, your belief is unfalsifiable. And never assume you must be right simply because you can’t be proven wrong.

To learn more

Wired, Why You Can Never Argue with Conspiracy Theorists

Skeptical Inquirer, A Field Guide to Critical Thinking

Only looking at falsifiability to assert potential validity in science is a testimony to blissful ignorance of the well-established Incompleteness Theorems of metamathematics (“Godel”). Faith and Non-falsifiability is at the heart of science. Dig a bit, and one always find hypotheses, not proofs.

When Lamarck published biological evolution theory through progressive transformation of mollusk fossils, in 1807, his proofs, obtained below the microscope, for decades, infuriated the dictator Napoleon (who may never have looked through a microscope). Napoleon found an ally in another biology research professor, Cuvier, who had (also perfectly correct) “proofs” of catastrophism (such as the sudden disappearance of dinosaurs). We know know that they were both correct. They simply demonstrated different hypotheses…

For example all the Foundations of Quantum Physics rest on plenty of these, and have rested on them… For a century (causing lively philosophical debates among physicists).

It is only now that some of these underlying hypotheses are coming out of faith, philosophy, wishful thinking and Einstein/Bohr/Born cult, to be tested EXPERIMENTALLY. The technology did not exist previously to engage in said experiments (say attosecond clocks).

And guess what? To interpret what the new experiments may mean, say about Quantum Tunneling speed, new THEORETICAL science has to be created… such as “complex time”… And that is itself controversial.

How does one proves oneself wrong? By arguing with potential contradictors. So a necessary dose of sadomasochism is an indispensable help. This is the essence of the Socratic method, and why Socrates is always arguing with silly contradictors, or even an ignorant boy who knew no mathematics (to prove that, after all, he knew it, without knowing that he knew it).

Personally, thus, I always look for lively debate, and considers that urge a moral drive. Thus, I argued by own SQPR with… Richard Feynman. Unfortunately, he agreed with me (“that would change everything”)…

Pingback: 2021 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #30 | Climate Change

Thanks for including this article on your weekly news roundup!

Pingback: Articles Of The Week August 1, 2021 - The Massage Therapist Development Centre

This is an excellent series of articles. It occurs to me that combined with John Cook’s FLICC and Cranky Uncle these articles could form the basis of a course on critical thinking for high-school pupils. (Where I came from pupils went to school and students went to university — a useful distinction to my mind.)

Learning about critical thinking is sorely needed by the youth of today. It is the antidote to the disinformation that is currently engulfing us. Disinformation is dangerous; it can kill. One needs the ability to think critically to avoid been deceived by disinformation.

Why thank you for such a kind comment! And you’re not wrong about John Cook’s work…and I use it in class. 🙂

I don’t know how familiar you are with my site, but Thinking Is Power started from a course I developed to teach critical thinking and science literacy. I hope to encourage more science educators to re-think how we teach science, especially for non-majors.

https://thinkingispower.com/from-non-majors-biology-to-critical-thinking-an-educators-journey/

Thanks again!

Pingback: Quackery grifting — easy money for pushing pseudoscience

Pingback: Tipps zur Faktenüberprüfung: Suche nach zuverlässigen wissenschaftlichen Informationen

Pingback: TIPPS ZUR FAKTENÜBERPRÜFUNG: SUCHE NACH ZUVERLÄSSIGEN WISSENSCHAFTLICHEN INFORMATIONEN

Sorry, this article preaches bad philosophy.

https://kungfuhobbit.medium.com/the-demarcation-problem-388fab441c40

https://iep.utm.edu/pseudoscience-demarcation/

It’s true that defining the boundary between science and pseudoscience is challenging, and there’s no clear-cut answer. But the concept falsifiability still has value, in science and in critical thinking.

A great article worth pondering in a post truth world. Thanks.

Pingback: When Facts Fall Short: Tackling Unfalsifiable Claims in Sustainability Education – Evidence-informed Sustainability Education (EvSusEd)