A long time ago six blind men lived in a village in India. The men had heard stories about elephants from the other villagers, and they were very curious.

One day the villagers arranged for the men to visit the palace and experience an elephant for themselves. Each of the blind men approached, and then touched, the part of the animal that was closest to them.

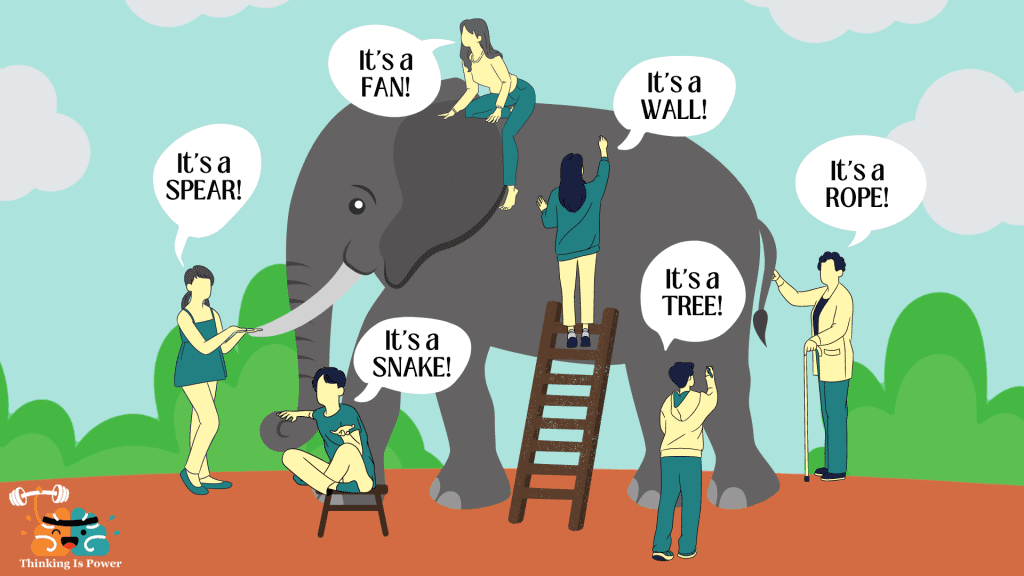

The first man put his hand on the elephant’s side. “Oh, of course! The elephant is just like a wall!”

The second man felt the elephant’s tusk. “You are wrong. The elephant is like a spear.”

The third man touched the elephant’s trunk. “You’re both wrong. The elephant is obviously like a snake.”

The fourth man grabbed one of the elephant’s legs. “I understand perfectly! It’s clear the elephant is like a tall tree.”

The fifth man was tall and reached for the elephant’s ear. “You are all mistaken! The elephant is like a huge fan.”

The sixth man was only able to grasp the elephant’s tail. “How could you all be so wrong?!?! Anyone with any sense would see the elephant is just like a rope.”

Long after the elephant moved on, the blind men continued to argue about what an elephant was. They called each other names, accused the others of lying, and scoffed at their stupidity.

Each was convinced they were right and the others were foolish. Of course, each man was partly right, but all were wrong. Listening to each other’s perspectives would have helped them better understand the true nature of an elephant.

We are all more blind than we realize. Our subjective experiences are limited, and yet we’re often convinced they’re the absolute truth. But being overconfident prevents us from learning or changing our mind. If our goal is to better understand the true nature of reality, we must recognize that our perceptions are incomplete, flawed, and biased, and be open to hearing the experiences of others.

To Learn More:

Vox: Reality’ is constructed by your brain. Here’s what that means, and why it matters.

Wikipedia: Blind men and the elephant

Pingback: On Writing Biographies | Hot White Snow

Pingback: Vier Gründe, warum Anekdoten keine guten Beweise sind

Pingback: How to love the freedom of leaderless fandom, and fight the flipside of organized abuse | Dogpatch Press

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 3/15/25 I Wish I Could Pixel Like My Captain Kate (Janeway) | File 770