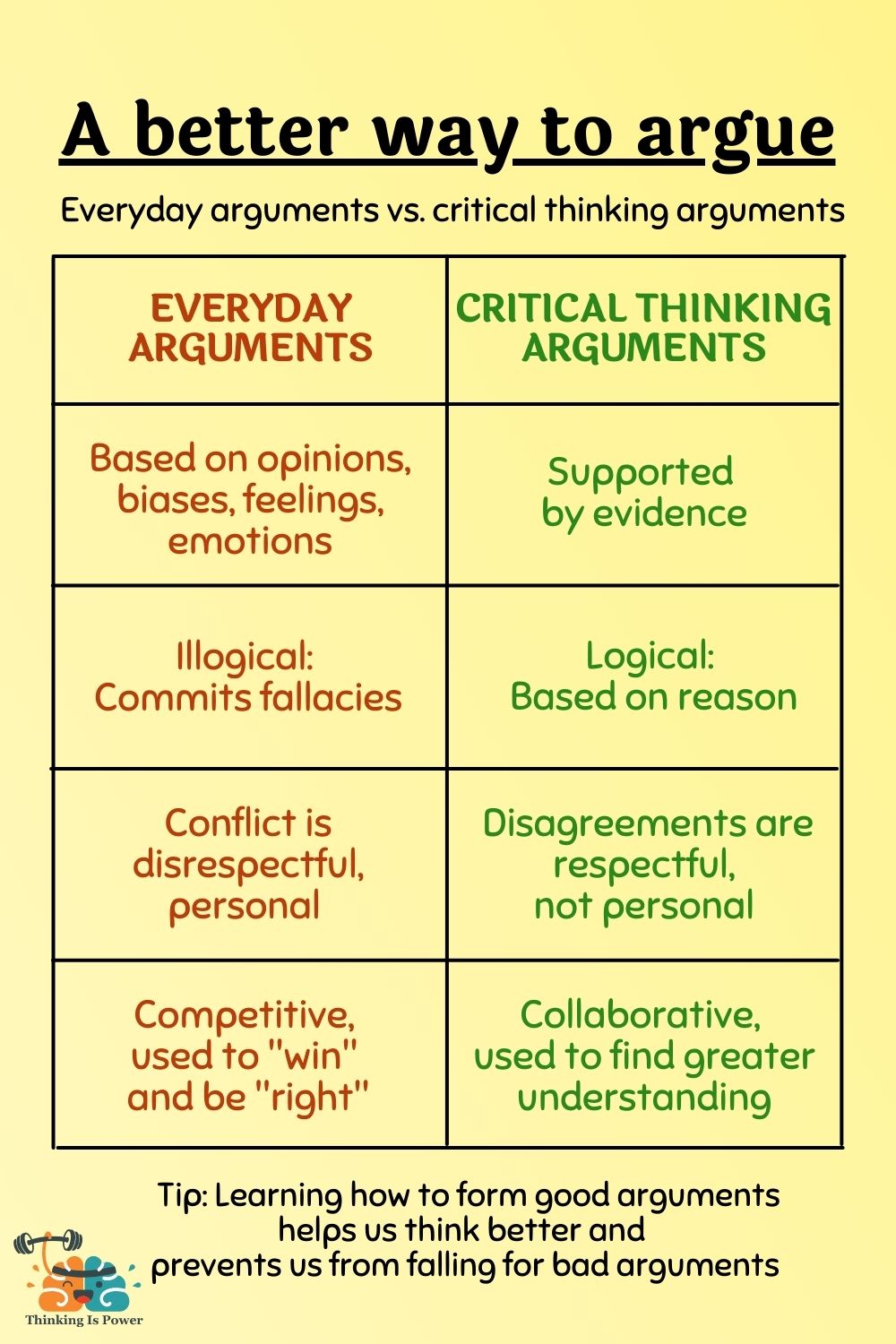

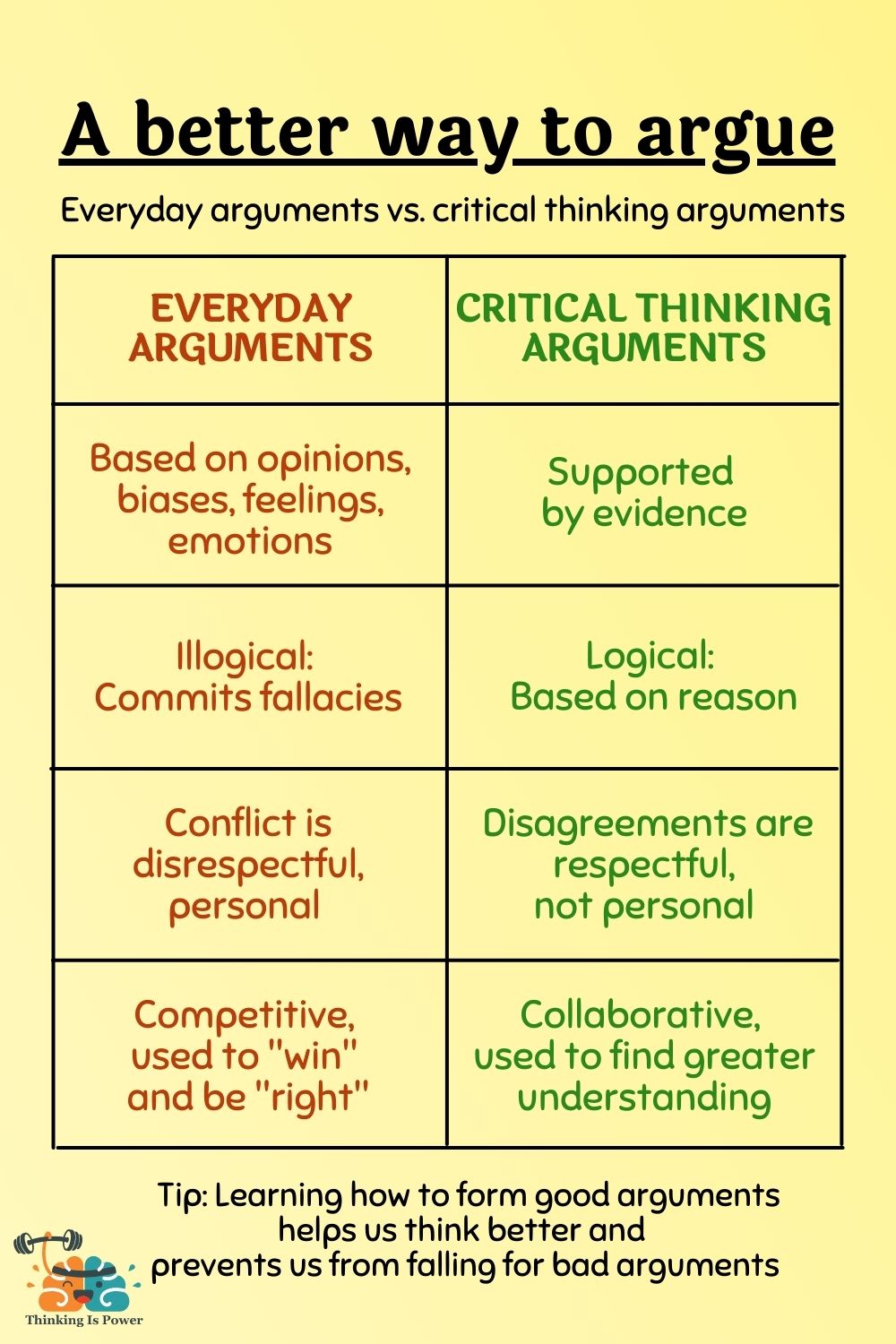

What comes to mind when you think of arguing? Yelling? Name calling? Witty comebacks? Uncomfortable family get-togethers, or the comment sections on social media?

To most people, arguments are heated exchanges over differing viewpoints. Generally, they’re not very productive, and they understandably turn a lot of people off.

But in critical thinking, arguments are essential for discovering the truth. Learning how to argue will improve your thinking and your ability to persuade others. It will also prevent you from falling for others’ illogical or misleading arguments.

The value of arguing

Before we dive into the specifics of arguments, it’s important to understand why we should argue.

The short answer is: To learn.

No matter how smart or educated an individual is, their knowledge and understanding are limited. There is always more to learn, and that’s where arguments come in.

Imagine a disagreement between two people. Person 1 argues what they think is true and why. Person 2 does the same. If the two of them work together, by listening to each other’s reasons for why they believe what they do, and being open to new evidence, they collectively stand a better chance of understanding reality than either would on their own.

In this way, arguments are tools for finding the truth, not weapons to win. The goal is to get it right, not be right. You’re on the same team!

It’s easier said than done, of course. But keeping in mind the following will help:

- Principle of charity: Interpret others’ statements in the most rational way possible. Avoid assuming they are ignorant or lying, and assume any errors are unintentional. In short, give people the benefit of the doubt.

- Intellectual humility: Recognize that you might be wrong! Essentially, know the limits of your knowledge, avoid being overconfident, and be willing to change your mind.

- You are not your argument: Keep your identity small and you won’t feel threatened by an opposing argument. You’ll also be able to objectively evaluate your own conclusions and change your mind.

Hopefully my argument that arguing is a good thing has intrigued you enough to learn more!

What is an argument?

The word argument has different meanings. Most people think of an argument as a quarrel, which requires a disagreement. In logic, however, arguments are used to convince or persuade using evidence and reasoning.

In this usage, an argument has to include two parts:

- A conclusion, or claim

- One or more premises, which provide evidence or support for the claim

Essentially, an argument says, “Here’s what I believe, and why,” with the “why” being the most important part. Critical thinkers require evidence to accept claims. And skeptics proportion their beliefs to the evidence: Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and claims made without evidence can be dismissed.

Whoever makes a claim bears the burden of proof to provide evidence. For this reason, an argument must have at least one premise. While people commonly state their views on issues without providing reasons, those aren’t arguments, but unsupported assertions.

While there are different types of arguments, they all have the same basic structure. The major difference between them is the level of proof they provide for the conclusion. The short version is that most of the arguments we make and hear on a daily basis do not provide absolute certainty…..which is a great reminder to us to not be too confident about our beliefs.

Breaking down arguments

From ads to family and friends to the media, we hear arguments all day, every day. We regularly make arguments, too.

When faced with any particular argument, the question is: Does the argument provide sufficient reason to accept the conclusion?

To answer that question, we first need to be able to identify the parts of an argument.

Step 1: What are the premise(s) and the conclusion?

In the “real world,” people don’t say, “Here is my first premise,” and “Here is my conclusion.” So you’re going to have to figure it out yourself.

The easiest way to identify the parts of an argument is to start with the conclusion. Basically, what are you being asked to accept?

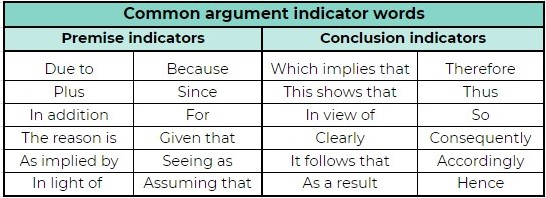

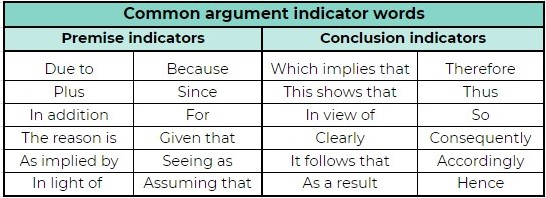

Another technique is to look for indicator words, which are commonly (but not always) used in arguments.

For example, consider the following argument:

“You should cook dinner tonight, because I’m going to be home late.”

Remember to start with the conclusion, which is, “You should make dinner tonight.” “Because” indicates the premise, which is “I’m going to be home late.”

People often come to different conclusions because their arguments are based on different premises. So if you find yourself in a disagreement, clearly identify why each of you think your belief is true. Then move on to….

Step 2: Are the premises true?

Premises are the reasons to accept a conclusion. So now we need to evaluate the evidence. What do we know about the premises? Are they true?

For example, consider the following argument:

“It only snows in February. It’s snowing, so it’s February.”

The conclusion is, “It’s February.” This argument has two premises, which are: (1) “It only snows in February,” and (2) “It’s snowing.” Since the first premise is not true, we don’t have a good reason to accept the conclusion.

Clearly arguments with false premises can lead to false conclusions.

Unfortunately, it’s not always this obvious. For example, we may not know for sure if a premise is true. Another potential problem is a premise that’s subjective, such as an opinion, preference, or judgement, that is not objectively true or false.

For example, consider the following argument:

“Everyone should have a cat. They’re much better than dogs.”

The conclusion is “Everyone should have a cat.” The premise, “They’re much better than dogs,” is an opinion, and therefore subjective. So this isn’t a very good argument.

Now that we’ve evaluated the premises used to support an argument, we can move on to…

Step 3: Are there hidden premises?

Many arguments have unstated assumptions that are required for the conclusion to be true. These hidden premises, though not explicit, provide reasons to accept an argument’s conclusion. Unfortunately, this requires us to fill in the gaps if we are to properly evaluate an argument.

Why do arguers hide premises? Sometimes it’s just laziness. Also, it’s possible they don’t have a very good understanding of their own argument. And there’s always the chance that they know they don’t have a good argument, so they’re being sneaky or devious.

The root of many bad arguments is a hidden premise. For one, if the hidden premise is false, you could fall for a bad argument. And if the source of disagreement is based on a hidden premise, it will be nearly impossible to resolve.

The point is, to properly evaluate an argument, we need to clearly identify all premises and assess their truthfulness.

For example, consider the following argument:

“Dmitri is a cat, therefore Dmitri is a mammal.”

The conclusion is “Dmitri is a mammal,” and the stated premise is “Dmitri is a cat.” However, there is a hidden premise, which is “Cats are mammals.” In this case, the conclusion is true with and without the hidden premise.

But let’s try another example:

“Lawrence died, so he must have been murdered.”

The conclusion is “Lawrence must have been murdered,” and the stated premise is, “He died.” The hidden premise in this case is, “People only die from being murdered.” However, we know that people can die from causes other than murder. So restoring the hidden premise shows we should reject this argument.

We’re almost done!

Step 4: Does the argument contain logical fallacies?

Logical fallacies are flaws in reasoning that weaken or invalidate an argument. Whether they’re used intentionally or unintentionally, they can be quite persuasive. Logic doesn’t come naturally, so unless you learn how to identify fallacies you could be fooled by a faulty argument (or make one yourself!).

No matter how rational we think we are, we don’t tend to follow evidence to a conclusion. Instead, we start with our desired conclusion and construct an argument around it, by searching for premises we think support our conclusion and using logical fallacies to make a bad argument work.

While there are about a trillion fallacies, familiarizing yourself with the more common ones is probably a good idea. However, the most important thing is to be able to recognize that there’s a flaw in an argument.

[Learn more: Guide to the Most Common Logical Fallacies]

As an example, consider the following argument:

“GMO foods are unhealthy because they aren’t natural.”

The conclusion is “GMO foods are unhealthy,” and the stated premise is “They aren’t natural.” The hidden premise in this case is “Things that aren’t natural are unhealthy.” The problem with this premise is that it commits a logical fallacy known as the appeal to nature. Basically, “natural” is quite difficult to define, and we can’t assume that something is healthy or unhealthy based on its presumed naturalness. By explicitly stating the hidden premise, and recognizing the flaw in reasoning, we see that we should reject this argument.

The take-home message

Arguing gets a bad rap, because too many of us don’t know how to do it well. But arguing has many benefits, such as:

- Improving discourse and creating connections.

- Increasing our understanding of issues and each other.

- Protecting us from being fooled by bad arguments.

- Helping us think more clearly and logically.

Like anything, learning how to argue takes practice. Luckily, daily life provides us with plenty of opportunities! Depending on where you are in your journey, practice:

- Identifying conclusions and premises, and distinguishing arguments from unsupported claims.

- Evaluating the premises for truthfulness, and searching for hidden premises. Basically, is there enough evidence to accept the conclusion?

- Determining if the argument commits any reasoning errors, or logical fallacies.

Finally, remember the golden rules of argumentation:

- If you make a claim, back it up with evidence.

- Apply the principle of charity, and give others the benefit of the doubt.

- Most arguments don’t provide 100% proof of a conclusion, so adjust your confidence accordingly.

- Be humble! You might be wrong, and you should always be open to changing your mind with evidence.

Together, we can work towards more productive argumentation!

To learn more:

John Cook: How to spot and tag misinformation

Lumen Learning: Critical Thinking & Reasoning: Logic and the Role of Arguments

Thanks to John Cook, Lynnie Bruce, and Anthony Trecek-King for their feedback.

“Everyone should have a cat. They’re much better than dogs.” Surely these are two separate conclusions, the second one being: ” Cats are much better than dogs.” Each of these conclusions need its own premise.

It’s certainly a poor argument, and for reasons beyond the subjectivity of its premise. For example, there’s a hidden premise as well:

Hidden premise: Everyone should have either a cat or a dog.

Explicit premise: Cats are much better than dogs.

Conclusion: Everyone should have a cat.

Thanks for the comment!