Scarlett’s* post on my town’s Facebook page was going viral. “Be on the lookout for poison oak!” it warned, alongside an image of her nasty rash.

Commenters were sharing their own encounters with poison oak, and a few with poison sumac, all while doing yard work.

And while Scarlett’s intentions were good, it was misinformation.

In the comments, I identified myself as a plant ecologist and attempted to clear up a few misconceptions: There is no poison oak in Massachusetts. Poison sumac is a wetland plant. The most likely culprit was poison ivy, a native plant that’s ubiquitous in our area.

Unfortunately, many didn’t accept my explanation—including the original poster—as her doctor had told her it was poison oak.

I tried again. All three plants—poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac—contain the same allergenic compound, urushiol, that can cause contact dermatitis. So while the doctor’s diagnosis was likely correct, they were almost certainly wrong about the offending plant.

Alas, Scarlett (and most others) remained unmoved.

Thinking Critically about Poison Ivy

Scarlett’s medical doctor relied on their knowledge and experience to diagnose and treat her rash, an application of critical thinking outside of my purview. As an expert in plants, here’s how I approached this issue.

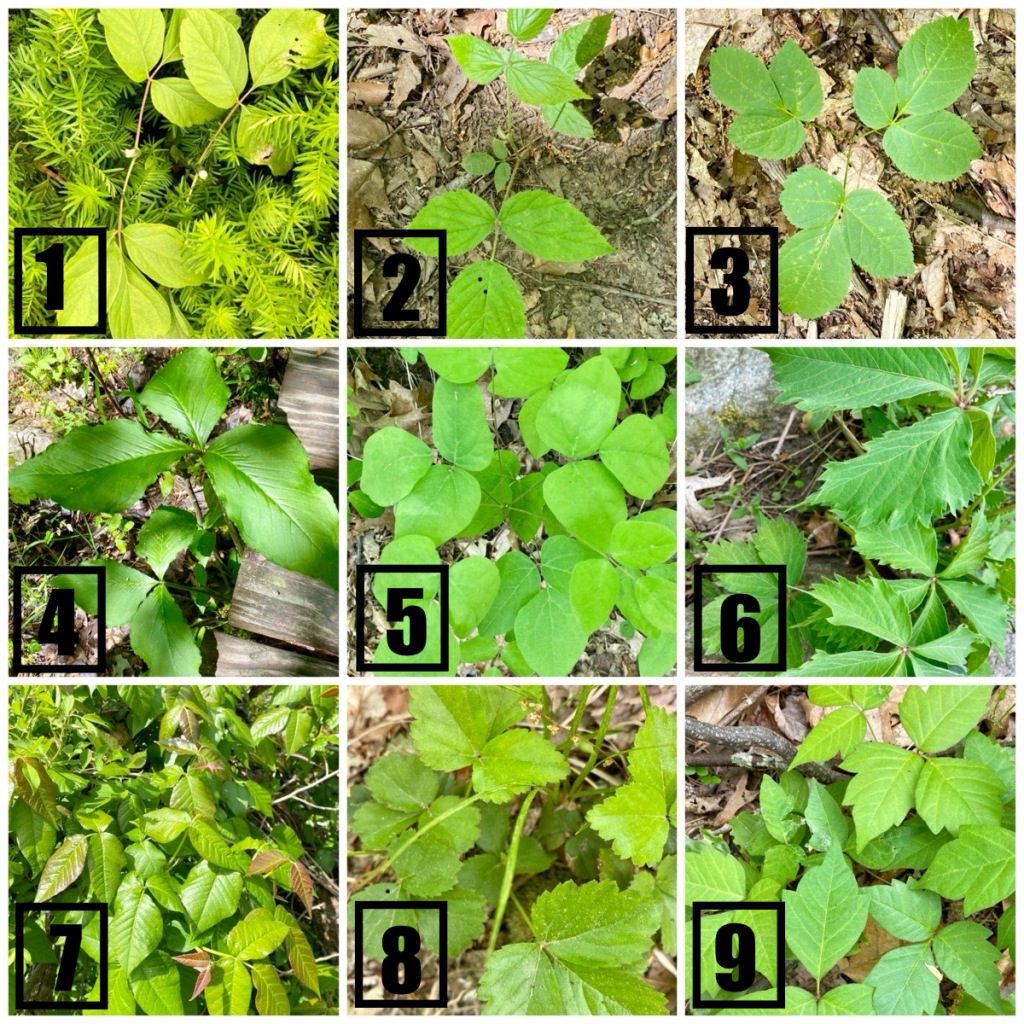

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans [L.] Kuntze) can be difficult to identify, as it has seemingly endless phenotypic variations, changing its morphology and growth form depending on its immediate habitat, growth stage, and time of year.

Many have heard the adage “Leaves of three, leave it be”. But poison ivy’s leaflets aren’t always clearly found in threes. And to make matters worse, there are several harmless plants commonly mistaken for poison ivy, such as Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch.), boxelder (Acer negundo L.), Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum [L.] Schott), brambles (Rubus spp.), American hog-peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata [L.]) Fern.), and wild strawberries (Fragaria spp.).

Poison ivy is adapted to a wide range of environmental conditions, and is quite happy in suburbia. It thrives in grasslands and forests, creeping along the ground or up into canopies, and will readily colonize disturbed areas. (I’ve seen it growing in a grocery store parking lot!)

In short, if you live in the Northeast, being able to identify and avoid poison ivy is an essential skill.

All members of the genus Toxicodendron contain urushiol, an oily compound that can cause allergic reactions in most people, ranging in severity from itchy rashes and blisters to anaphylactic shock. Interestingly, only humans (and a few other primates) react to urushiol… and not all humans, either! (A fact my mother has tested frequently.) However as with any allergen, repeated exposure can lead to future immune reactions.

If we want to determine the source of urushiol, we need to consider what plants are most likely to be found where the exposure occurred.

While it’s notoriously difficult to define and classify species, botanists currently recognize five members of genus Toxicodendron in North America:

- Poison sumac (T. vernix [L.] Kuntze) is a shrub or small tree found exclusively in wetlands in the Eastern United States.

- Western poison oak (T. diversilobum [Torr. & A. Gray] Greene) is a woody shrub or vine that’s found from California to British Columbia.

- Eastern poison oak (T. pubescens [Mill.]) is a shrub that’s found throughout the Southeast.

- Western poison ivy (T. rydbergii [Small ex Rydb.] Greene) is a shrub that’s found throughout Canada and the United States, except for the Southeast and California.

- Eastern poison ivy (T. radicans [L.] Kuntze) is a vine or shrub that’s found throughout the Eastern part of the United States and Canada.

In conclusion, the most likely culprit for the rash in a Massachusetts yard is Eastern poison ivy.

Thinking Critically about Experts

There are endless varieties of experts, and part of what makes humans so successful is that we specialize and share knowledge. For example, pilots, farmers, medical doctors, wastewater treatment operators, etc., all have specific expertise that the rest of society relies on.

Experts possess a deep knowledge that’s essential for thinking critically about an issue. They’re aware of the nuances, uncertainties, and complexities within a domain. And they’re aware of what they don’t know. These are key differences between experts and authorities, who often use a position of power and “because I said so” in place of evidence and reasoning.

[Learn more about the appeal to authority fallacy.]

Without expertise, attempts at thinking critically are often superficial and can lead to misconceptions and flawed judgments. It’s unrealistic to be an expert about everything, and fortunately, we don’t have to. The key is to be able to find reliable knowledge, which means using our critical thinking skills to evaluate experts to determine who is worthy of our trust.

Experts in scientific fields generally have

- Formal education, including advanced degrees

- Credentials or licenses from reputable institutions

- Significant experience

- Publications and research

- Favorable recognition by their peers

- Memberships in, leadership positions in, and/or awards from professional organizations.

Importantly, not all experts are created equal, and some are a great deal more reliable than others! Look out for red flags, like those who are

- Unqualified, such as many influencers or celebrities

- Fringe outliers who promote controversial ideas

- Biased, often due to conflicts of interest

- Operating outside of their area of expertise

- Contradicting widely accepted consensus knowledge

While we often rely on experts without a second thought, there are times we distrust their conclusions, such as those that threaten our identity, ideology, or important beliefs. Some of this distrust is a direct result of disinformation sources using fake experts to sow doubt about a scientific consensus. (Both the tobacco and oil industries had great “success” with this tactic.)

Experts can be wrong, of course. Expertise is a tool, not a guarantee. However, experts are more likely to be right than non-experts. And if experts have reached a consensus there’s even less chance that they’re wrong. If experts don’t agree, then it’s a different matter altogether. Just make sure that the disagreement is real and not the result of a concerted disinformation campaign or being fooled by our own biases.

Importantly, critical thinking is more than problem solving. It’s being aware of our biases, emotions, assumptions, and motivations, and being honest with ourselves about what we know (and don’t know). It’s very difficult to be objective if we’re emotionally triggered or defensive. Motivated reasoning is powerful, and if we’re looking for reasons to discount or distrust experts, we will find it. But it’s at our own peril, as we limit our access to reliable knowledge and therefore our ability to make sound decisions.

Thinking we know more than experts is an exercise in hubris and one that can backfire. Contrarianism, and dismissing expert opinion because it’s perceived to be an “official narrative”, isn’t as empowering as it might feel.

As always, it’s essential to maintain healthy skepticism. When evaluating experts, cross-check their conclusions with other experts, and ask them to explain their evidence and reasoning. But a wholesale rejection of expertise reveals more about our motivations and biases than it does about the limitations of experts.

The Take-Home Message

To her credit, Scarlett realized she needed professional advice for her rash. Yet she failed to recognize that medical doctors and ecologists have different areas of expertise, and as a result remained convinced that she had poison oak. Unfortunately for Scarlett, poison ivy is everywhere, and if she doesn’t learn how to identify and avoid it, her next allergic reaction could be more severe.

Thinking critically to solve a problem requires content knowledge, and it’s impossible to have sufficient expertise to think critically about every issue. If our goal is to align our beliefs with reality, to the best of our abilities to do so, it behooves us to recognize the limits of our knowledge and apply our critical thinking skills to seek out trustworthy experts. Because outside of our areas of expertise, we’re all Scarlett.

To Learn More

- 1000-Word Philosophy, What is an Expert?

- Tom Nichols in Politico, How We Killed Expertise (and Why We Need It Back)

*Name changed, but based on a true story.