Note: This article is the first of a two-part series on “doing your own research.” To read the second article click here.

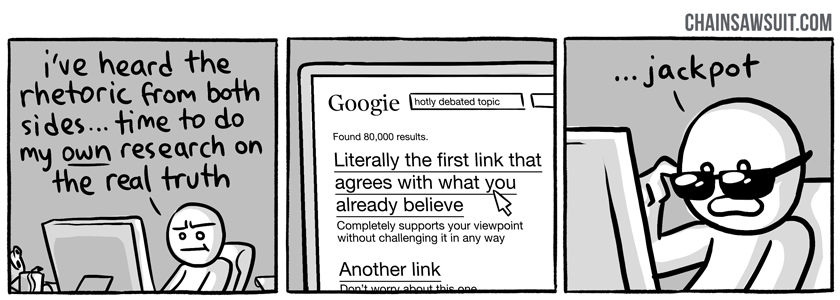

The phrase “do your own research” seems ubiquitous these days, often by those who don’t accept “mainstream” science (or news), conspiracy theorists, and many who fashion themselves as independent thinkers. On its face it seems legit. What can be wrong with wanting to seek out information and make up your own mind?

The problems with “doing your own research”

1. That’s not what research is.

Definitions matter! When scientists use the word “research,” they mean a systematic process of investigation. Evidence is collected and evaluated in an unbiased, objective manner, and those methods are made available to other scientists for scrutiny and replication.

Research can also include gathering and synthesizing existing research to explore a question or topic. This secondary research requires the ability to search for relevant information, evaluate sources for credibility, and analyze and interpret methodology and data. As with primary research, developing these skills takes practice and experience.

Conversely, when someone says they’re “doing their own research,” they often mean using a search engine to find information that confirms what they already think is true. We are all prone to confirmation bias, and the effect is especially powerful when we want (or don’t want) to accept a conclusion.

The goal of science is to understand reality. Built into the process is a recognition that all individuals have flawed perceptions and biased thinking, which is why researchers try to prove themselves wrong, not right. Additionally, the scientific community provides checks and balances on each others’ work.

2. You might not know as much as you think you do.

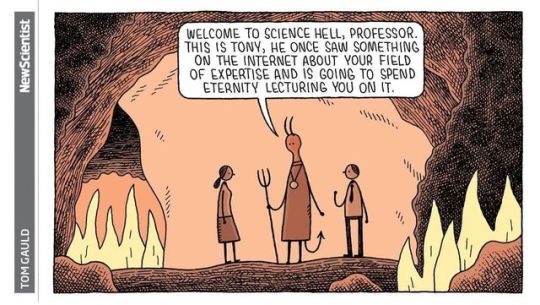

Unless you’re an expert in the field you’re “researching,” you’re almost certainly not able to fully understand the nuance and complexity of the topic. Experts have advanced degrees, published research, and years of experience in their sub-field. They know the body of evidence and the methodologies the researchers use. And importantly, they are aware of what they don’t know.

Can experts be wrong? Sure. But they’re MUCH less likely to be wrong than a non-expert.

Thinking one can “do their research” on complex scientific topics, such as climate change or vaccines, is an exercise in the Dunning-Kruger effect: you’ll be overconfident… but wrong. Studies have found that those who think they can “do their own research” are more misinformed about scientific issues like COVID-19, and online searches to evaluate misinformation push people towards low-quality sources that misinform them even further.

Yes, information is widely available. But that doesn’t mean you have the background knowledge to understand it, so it’s important to know your limits.

The process of science is messy

Science is messy. For example, climate change research involves experts from a variety of fields (e.g. earth sciences, life sciences, physical sciences) and settings (e.g. academia/government/industry), from nearly every country on earth, each looking at the issue using different methods. Their findings have to pass peer review, where other experts evaluate their work before it can be published.

The literature is also messy, as different studies provide different types and qualities of evidence. Different studies also might reach slightly different conclusions, especially if they use different methodologies. Findings that are replicated have stronger validity. And when the various lines of research converge on a conclusion, we can be more confident that the conclusion is trustworthy.

And then there’s the news, which tends to report on new, unique, or sensational findings, generally without the detail and nuance in the literature.

All of this messiness can leave the public thinking that scientists “don’t know anything” and are “always changing their minds.” Or that you can believe whatever you want, as there’s “science” or a “study” or even an “expert” that supports what they want to be true.

Waiting for “proof”

Most people recognize that science is trustworthy. After all, we can thank science and resulting technology for our modern quality of life. Unfortunately, there are many misconceptions about the process, including the enduring myth that science proves.

Scientific explanations are never proven! Instead, science is a process of reducing uncertainty. Scientists set out to disprove their explanations, and when they can’t, they accept them. Other scientists try to prove them wrong, too. (And scientists LOVE to disagree. Anyone who thinks scientists are able to conspire has never attended a faculty meeting or conference.) The best way for a scientist to make a name for themselves is to discover something unknown or disprove a longstanding conclusion.

The process of systematic disconfirmation is designed to root out confirmation bias. Those insisting on “scientific proof” before accepting well-established science are either misled or willfully using a fundamental characteristic of science to avoid accepting the science.

Why we should trust experts and the process of science

Back to “researching.” The danger is that uninformed or dishonest people can cherry pick individual studies, or even an expert or two, to support a desired conclusion or to make it look like the science is more uncertain than it is… especially if they don’t want to accept it. And if we’re being real, many who are “doing their own research” are doing so to deny scientific knowledge. Unfortunately, the dangerous mixture of confirmation bias, misplaced trust, limited knowledge, and overconfidence is the perfect storm for being misled, and for many scientific issues the price of being wrong is just too high.

Ultimately knowledge is a community effort. We don’t think alone… and that’s what makes humans a successful species. The problem is that we fail to recognize where our knowledge ends and the community’s begins. That’s why, for anyone who isn’t an expert in a particular field, the most reliable form of knowledge is the expert consensus. No “research” involved.

To learn more

Forbes: You must not ‘do your own research’ when it comes to science

Thinking Is Power: Don’t be fooled…Fact Check!

My experience with those who say “do your own research” is that they use it as an avoidance mechanism when they are challenged to provide the sources for their claims. My response to that is that statements which cannot be sourced are opinion, not fact, and should be labeled and treated as such.

There are different uses of the phrase. This post was addressing those who think they can “do their own research” on various science topics, which usually means they go searching for whatever sources confirm what they already believe.

Your comment addressed the defensive version in which someone makes a claim but avoids the burden of proof by asking another person to research it.

Thanks for the comment!

Excellent. Well done.

People ‘doing their own research’ are not actually researching at all, but are merely doing a bit of a literature search, unaware of or dismissing the likely cognitive bias often arising. Many vocal proponents of any theory – but especially conspiracy theories or pseudo-scientists – have strong active/pragmatist tendencies (look it up) whilst the best researchers have stronger reflector or theorist tendencies. This means that they are more likely to grasp the first ideas that seem to fit, rather than looking at the full range of options. ‘For every problem there is a simple, elegant compelling wrong answer’.

Any ‘research’ arising is not fundamental enough to be sound science. Rather it is often badly designed meta-study – the worst kind.

I am slightly slighted by the insistence on ‘higher degrees’, since they merely demonstrate that people have learned to apply their analysis and critical thinking in a demonstrable pierce of work. The skills and expertise are not limited to academia. Others do have the necessary skills, often honed during a first degree.

Unless the work is very, very specific and very, very close to the topic in hand then a more generalised critical ability suffices just as well and may lack the inherent biases that being close to a topic area may bring. The incisive and insightful skills needed to dissect any issue are often learned much earlier, at GCSE/A-level/high-school and bachelors/first degree (but I accept it is forgotten by most people within a few years of leaving education. We teach these skills in the workplace too. I often describe my job as ‘professional sceptic’. My colleagues and I critique what are essentially dissertations.

This does not mean that anyone is capable or competent to comment, but it does mean that the uninformed

Thinking is power? You seriously want me to just trust someone without thinking for myself?

This post is bad on so many levels… If an Expert cant answer my questions and resorts to appeal of authority to “prove his point”, then I dont care how many degrees you have. I will listen to an Expert whom I identify as an Expert based on him impressing me with his expertise. If I ask a critical question (and for that you dont need to be an Expert or have studied or understand math or know what the scientic method…), then the Expert has to either provide an answer or admit that he doesnt know exactly.

Thank you for your comment.

I agree that experts should make their case based on evidence, and that’s what happens in science, where the evidence is evaluated by the community. If a thousand electricians all told me to replace the wiring in my house or there’s a danger of a fire, I’m going to trust their collective expertise.

The point of this post was about intellectual humility and knowing our limits. You don’t need to be an expert to accept the expert consensus, but you do need to be one to disagree with it.

“You don’t need to be an expert to accept the expert consensus, but you do need to be one to disagree with it.”

Why don’t people understand this critical point?

You are on a good path. This first section is just a preamble. Further reading is necessary, like clicking on links to fact checking, and then reading the second section.

Patience.

1st point is misleading. Distinction needs to be made between research to learn, and research for a debate. What they describe is research for a debate where you’re looking for evidence to support your argument. Nothing with either, but the author has made an erroneous assumption right off the bat.

People may not be as smart as an expert, but they can still learn. A funtional understanding of fundamental principles and concepts will make an expert’s presentation easier to understand, while make the audience harder to deceive with junk science. People should be encouraged to study independently.

Just because an expert or experts make a claim doesn’t mean it’s accurate. One should NEVER blindly believe an expert. They can have biases and conflicts of interest too. An argument must stand on its own merits regardless of who presents it.

It’s disturbing that the crux of this article is that people should approach science with belief instead of rationality. That they shouldn’t learn because they’re “not as smart as they think they are”.

Thank you for your comment.

The purpose of the post is intellectual humility, or recognizing the limits of our knowledge. In any area in which we aren’t an expert, the expert consensus is the best source of knowledge. If my child was sick and a hundred specialists said they needed a kidney transplant, I would get my child a kidney transplant, not go online to search for why they’re all wrong. It’s only in areas where our ideology conflicts with a robust conclusion that we question experts.

As for your point that people can learn and study independently… I agree. If one truly thinks the experts are all wrong, become an expert in that area and use evidence to make the case. Because it takes real expertise to disagree with an expert consensus.

“In any area in which we aren’t an expert, the expert consensus is the best source of knowledge”

This is a dangerous habit to adopt. Argumentum as populum is even worse than a basic appeal to authority. While gaining an expert-level understanding is ideal, it’s not a swift course of action. It’s better to first gain an understanding of a topic so you can detect if a group of experts could be honestly mistaken or tainted by bias.

Add to it the possibility that some experts in a field my be censored, thus generating the facade of a consensus, or that some experts may fear reprisal if they speak out. Remember in the news, some experts stayed silent because of who was President at the time. They didn’t want to be mistaken as supporting that person. These possibilities should remain in the back of our minds. So, that we look at things with a critical and skeptical eye.

That’s why, even though it’s acceptable for people to trust experts as they are more knowledgeable, they also need to reasearch the topic in order to verify the information is factual.

I would encourage you to read “Why trust science” by science historian Naomi Oreskes, as she addresses much of your concerns and misconceptions. I can recommend a variety of other scholars and their published works or books if you’d like to gain more expertise in this area.

As for me, I will still trust my plumber and the pilot flying my plane and my oncologist because spending a lifetime becoming an expert in every field isn’t possible. Like Confucius is credited as saying, “Real knowledge is to know the extent of one’s ignorance.”

Thanks

I would disagree that accepting the collective opinions of experts it is Argumentum ad populum. The experts are likely to be more well-informed and knowledgeable about the subject matter than non-experts. If ten doctors tell me I have Condition A and one doctor says I have Condition B, I am more inclined to go with the majority. Of course, all the ten doctors could be wrong. But the statistical chance of that one doctor being right is very unlikely. In life, we do not know the certainty of many things. We can only decide on the probability.

With regard to being censored, there has to be credible evidence of such action goin on. Or it would just be a conspiracy theory. We have to ask ourselves whether a claim can be falsifiable. If it is not, then there cannot be any intellectual argument in the first place.

Are you getting stuck in the weeds? The point of this article is to bring light to the misconceptions of a resent buzz phase. My mom thinks she is doing her research. She is so ignorant she doesn’t know when she should fact check. She just believes everything she reads if it confirms her bias and then she thinks she has learned something.

Pingback: How Skepticism Can Protect You From Being Fooled | Climate Change

I’ve noticed that the Venn Diagram of people that mock others for looking further into a topic past the media narrative and people that are easily manipulated because they “trust the experts/science” (a.k.a. mainstream news and social media feed) is a perfect circle. We all know by now that if the “experts” told you to walk off a cliff, you’d blindly listen to them and think that the people not walking off the cliff are ignorant fools that “did their research”. We have truly become a backwards society in the name of progressive politics.

We trust experts all the time, we just don’t think about it too much until the expert conclusion contradicts something we want (or don’t want) to believe. If 10 electricians separately concluded that I needed to fix the wiring in my house or risk a fire, I would believe them and get it fixed. I know I don’t know enough about wiring to tell all of the experts they’re wrong. It’s not backwards to trust experts, especially the consensus. It’s the prudent thing to do.

I want an expert flying my plane. Not an “expert” who “did their research.”

A systematic review is a much higher level of evidence than expert consensus. When I do a literature review, I like to check out the Cochrane database, rather than relying on expert consensus, case reports, etc. For me, unless the evidence is limited, expert consensus doesn’t cut it.

Thanks for your comment! If you haven’t yet, I encourage you to read the follow-up to this post, as it addresses your commment.

Lester suggests you would follow the advice of 10 electricians if they said setting fire to your house is the only way to protect it from fire. Respect for experts is part of common sense, not its abandonment.

I agree completely. An important part of knowledge is knowing where knowledge lives. We can’t all be experts in everything, so in the areas in which I’m not an expert, the prudent thing to do is to trust those who are.

Thanks for the comment!

Melanie

Great article. My favorite response to “I did my own research” is “You keep using that word. I don’t think it means what you think it means.”

As a skeptic (that is someone who follows the evidence, not just a denier), I do a lot of studying: physics, psychology, philosophy, critical thinking, thinking, and skepticism. I study this stuff and anything that catches my fancy. When I can, I go back to original studies. I also check Retraction Watch and see if I can find other commentary on the study. A recent example is reading the study that Johns Hopkins used to justify stopping gender transition operations. I did this because someone who did “research” informed me that they discovered that people who had undergone the operations were not any happier than before. So, I read the paper. Boring stuff. What I discovered was exciting to me. The study wasn’t that large, it surveyed (literally polled) people who underwent operations and people who decided not to. The result was a high percentage in both categories that were happy with their decision. Then came what I believe is abuse of statistics. They bounced the two groups against each other and the margin of happiness was “statistically insignificant” for people who underwent the operation. The problem was the groups were self-selecting, with the “control” group being those who chose not to undergo the operation. The real result of the study was people who elect to have the operation and the people who don’t were happy to a high degree with their choice, not the false conclusion foisted on the public. In my opinion the study was flawed due to small sample size, it was non-randomized, used a subjective opinion poll, used inappropriate methodology, and was nothing more than bias confirmation fueling motivated reasoning to reach a predetermined conclusion. It is tantamount to asking two professions how happy they are with their career choice and declaring the one you hate as not worth pursuing. In other words, junk science.

I studied the topic, but I wouldn’t call it research. If the evidence says something I didn’t agree with before, then I change my view.

Hi and thanks for your comment! As you can see, the “do your own research” trope bothered me enough that I felt the need to address it.

I’m not familiar with the study you’re discussing. Some issues are very difficult to study, such as when blinding and randomization aren’t possible or ethical. It’s always a good idea to look at the body of evidence and avoid the “single study syndrome.” That said, new areas of study are likely to only have small, observational studies, so we just need to make sure that we limit the conclusions we can draw based on the quality and quantity of evidence available.

Thanks again!

Melanie

Thanks for your response. The study I refer to is “Sex Reassignment. Follow-Up” (1979) by Meyer, MD and Reter (https://docksci.com/sex-reassignment-follow-up_5dbe4abb097c47ff7f8b4588.html). The sample size was 98, and 48 were lost to follow-up, so only 50 people. It took me a while to find a copy that wasn’t behind a paywall. Paul McHugh, the University Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and more importantly devout christian, used that study to shut down further gender transition operations at Johns Hopkins.

Thanks for finding the study. Motivated reasoning is very powerful…

“limit the conclusions we can draw based on the quality and quantity of evidence available”, may I point out here that “quality” might not only be the quality of the research that was conducted (was it good or bad?), but also the quality of the type of evidence that the research shows. The point being that evidence comes in not one form, but two forms: quantitative and qualitative.

If we observe that a hammer coming down causes our thumb to hurt, we discovered a quality and (generally) will not insist on a random control trial with hammers and our thumb in order to establish the pain was indeed caused by the hammer coming down. Experiments may demonstrate a quality, they form qualitative evidence. Experiments may demonstrate causality, which is a quality. If we repeat the experiment, the quantitative aspect increases, but the quality observed remains the same. Qualitative evidence only requires confirmation of being a true measurement, while quantitative evidence additionally requires the numbers to support it being a true measurement.

The word “quality” here has different meanings. The “quality” of evidence refers to the accuracy and reliability of results not a “qualitative” methodology.

Thanks for the comment

Melanie

It’s interesting whenever this topic is brought up because it almost seems to imply some sort of epistemic particularism about when to trust your sense perception. Clearly, finding information through a search engine is prone to many human biases that may obfuscate the process as human perception is fallible and individuals are prone to the Dunning-Kruger effect, Confirmation Bias, etc, there’s no denying this. Yet in order to understand expert consensus on topics you’d need to be able to know who the experts are and what it is they’re actually trying to tell you, and to do this you’d have to rely on the very same sense perceptions that are prone to exact same limitations. How do we know where to seek out expert knowledge, how can we know that we understand what they’re telling us, how do we know they’re even “real” experts? While doing this might be easier than understanding a complicated meta-analysis they both still come down to trusting that what we’re observing is true and acting in accordance with it.

Coming back to the article in question, I don’t understand how any real distinction can be made between laymen using their knowledge to identify and trust experts verses using their knowledge to identify and find valuable research. It can certainly be granted that experts are much more likely to be able to identify valuable research and are probably the only people able to put together the actual experiments in the first place, but it doesn’t follow from this non-experts who have discovered valid research going against a scientific consensus are automatically wrong due to their lack of credentials. The way I see it, in the same vein that if it appears an expert in a field is telling me something, I interpret it as such, find nobody that contradicts them, and am fairly confident I have no major defect in my senses, I hold studies that appear to come to certain findings in the same light. If I am truly blinded by Confirmation Bias this will surely come to light through flaws in the data being exposed or by being pointed to better studies that should clear up my misconceptions.

If your response is that I wouldn’t be able to understand the flaws or better studies directed toward me… well, then we’re just right back where we started of me having to be able to understand the experts in the first place to even be having this conversation.

Thanks for your comment. I answered most of your question on the follow up to this post: “How to do your own research.”

Best

Melanie

Pingback: Problem z „własnym riserczem” - naukaoklimacie.pl

Pingback: The problem with “doing your own research” - ParseAbout.com

Pingback: Watch The problem with "doing your own research" - Latest News Video

if we distill the contents of the post to a few words, it boils down to “trust us” (on many levels: trust the experts because they know better, trust the peer review, and so on). I happened to know a scientist (or few, to be sure). I also have an advanced degree in math.

Sad truth is, currently the trust is compromised. Repeatability crisis is ongoing state in the natural sciences, like biology, medicine and similar. It is even worse when we’re talking about behavioral sciences. In physics, an experiment resolves forces discussion of validity. Not so in economics: one cannot stage an experiment. (Yes, I know about work of Wassily Leontief and Poland’s transition to free prices, or about David Card’s natural experiments. As you pointed out, it is very nuanced.) I had a chance to observe “trust me” in practice: I was on jury duty, where expert witnesses provided evidences. Despite degrees, peer reviewed publications, and academical status they made elementary errors in using math (statistics to be sure). One could be an exception. Some 10-20 cast doubt. (Interestingly, experts for the both parties.)

Another aspect that undermines trust is lack of raw data. Very true, science is messy. Very true, it takes professional education, skills, and experience to evaluate any result. (I cannot read article in Nature. Just do not have enough qualification.) But refusal to share raw data is definitely an obstacle to establishing of the trust. In math, I can (theoretically) spend years and understand the proof. In absence of published data, I cannot. (Compare it to open source in programming: no, I am not going to read Linux code. but I am not denied access to it.)

Scientists are humans. As such, they are subject of all the common pressures. It is much easier to get grant to prove climate change than to disprove it. It is much easier to publish article that confirms current views than one that reverses them. It does not mean it would not be published. However the hurdle to overcome would be much higher. Which also means that meta-analysis is prone to the bias amplification. (And industry is not interested in research in harm it causes. After all, if it knows about harm, it is in much more difficult position.)

No, I am not going to do “my own research” (well, unless I am willing to stage an experiment and analyze its result, involving field professional). But I am still willing to question any result I find (on internet, or in professional / scientific publications).

This business of literature search to prove a hypothesis has been going on a long time. The only people on popular media who do what I would call “real science” are the “Myth Busters”. They do actual experiments starting from a hypothesis and follow the results.

Pingback: What it's, the way it works, and why it issues - eekorbit

Pingback: Tipps zur Faktenüberprüfung: Suche nach zuverlässigen wissenschaftlichen Informationen

The section “Why we should experts and the process of science” was probably supposed to say “Why we should TRUST experts and the process of science”… There’s a verb missing here.

Thanks for your work in putting these posts together!

Holy beans I can’t believe I missed that for that long!

Thanks for the comment. It’s fixed. 🙂

Melanie

Pingback: 1. Introduction to Passive Income - SEO AGENCY

Pingback: TIPPS ZUR FAKTENÜBERPRÜFUNG: SUCHE NACH ZUVERLÄSSIGEN WISSENSCHAFTLICHEN INFORMATIONEN

A resort to appeal of authority does not “prove a point”.

Don’t base anything on being impressed.

An Expert generally will both attempt to provide an answer and admit that he doesnt know exactly. The knowledge that nobody knows exactly is a mark of an expert.

Pingback: UNESCO's 2023 GEM Report: TCEA's Solution to the PD Problem • TechNotes Blog

I appreciate the article. Experts have become devalued in recent years. The result is that people think their own “research” is the equivalent of that done by experts. It did not help that some experts have sacrificed their objectivity for profit or gain, eg the experts who claimed lead in gasoline or smoking cigarettes were not harmful. Or the doctors who claimed opioids were not addictive. In each case, the “experts” had much to gain by making these claims. I suggest two modest adjustments to our thinking to try to avoid this: 1) look for consensus among experts, not just a minority, and 2)closely examine the incentives of an outlier “expert”— how do they benefit from espousing an implausible opinion? Money, fame, power?

Pingback: Crypto for life: Λεφτά στα κρύπτο για πάντα πλήρης οδηγός #divramiscrypto - Divramis Crypto Academy #divramiscrypto

Pingback: 1. Εισαγωγή στα παθητικά εισοδήματα #divramiscrypto - Divramis Crypto Academy #divramiscrypto