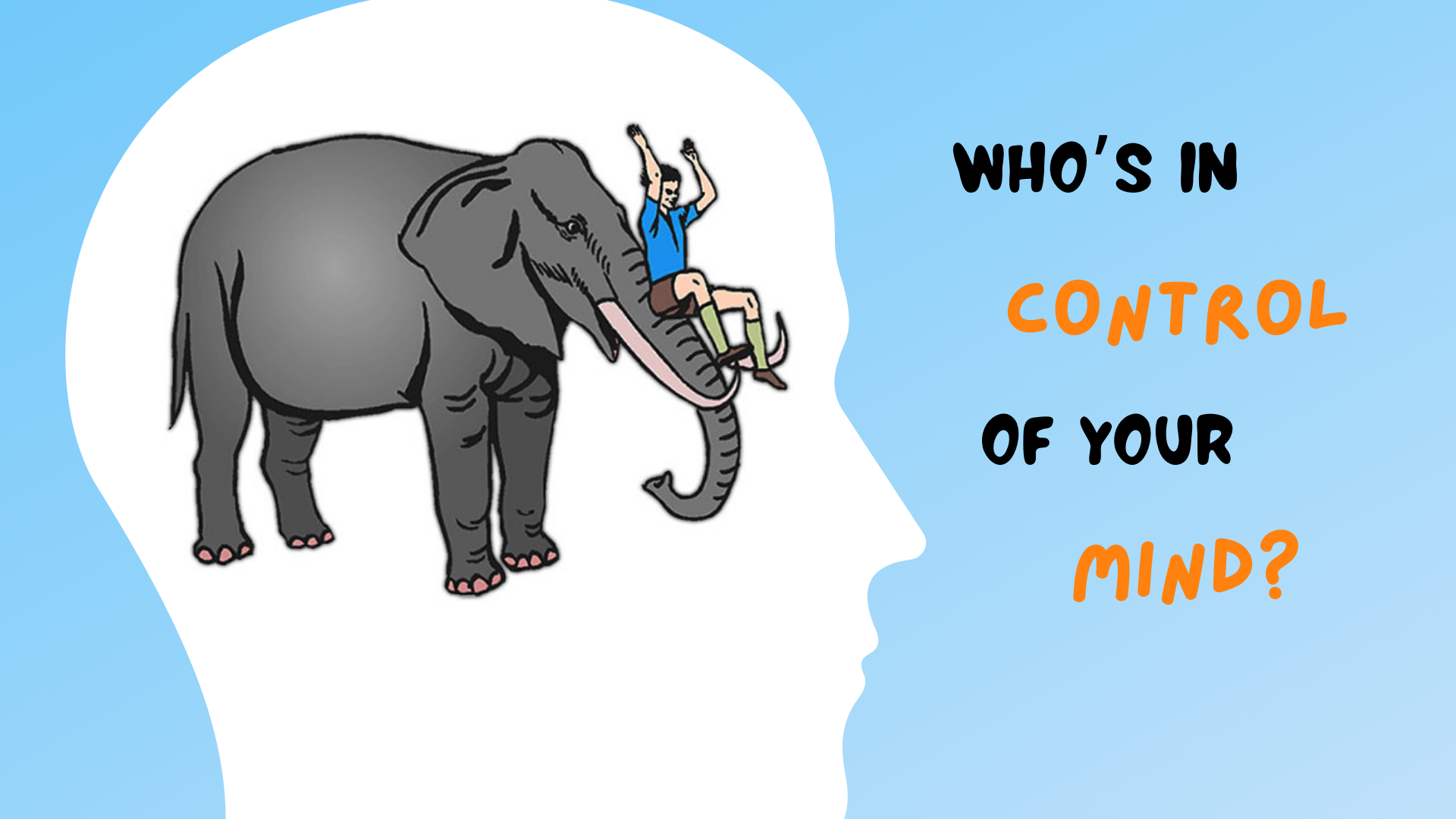

The elephant and rider inside your mind

We’re often told to “go with our gut” and “trust our instincts,” as if our intuition holds some special, innate wisdom that we can tap into for true knowledge.

But most of us are blissfully unaware of how emotional, tribal, and error-prone our thinking is.

Our divided minds

Imagine that your brain is divided into two parts: an elephant and a rider.

The rider is the part of your brain that you think of as you. It’s the conscious, thinking part of your brain that’s capable of logic and reasoning. It’s the part that we assume is in control, that decides what to believe and what choices to make.

But the rider sits atop of a very powerful elephant. The elephant is the unconscious, emotional part of your brain. It’s irrational and intuitive. And it mostly takes your rider for a ride.

The elephant part of your brain doesn’t turn off. It’s involuntary, helping you make fast decisions and navigate familiar tasks with ease. Most of how we think and react comes from this unconscious part of our brain.

Your rider, on the other hand, is lazy. It only engages when necessary, and even then, it’s happy to let the much more powerful elephant make most of the decisions. But all the while, the rider is confident that it’s in control and that it’s right.

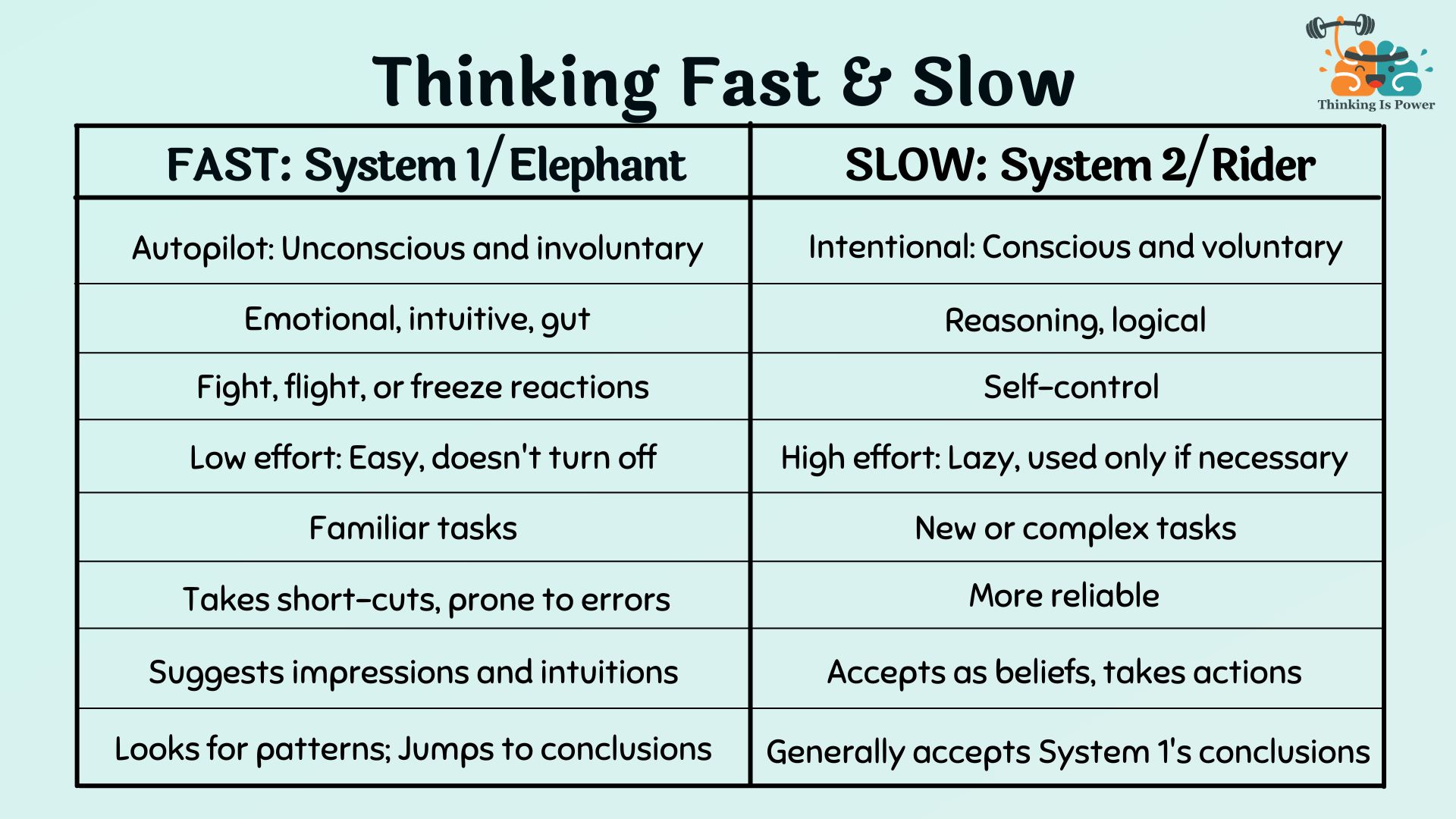

The elephant and the rider analogy, proposed by Jonathan Haidt, is one of the many theories that explain our divided minds. In his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” Daniel Kahneman referred to two systems in the mind, System 1 and System 2, where System 1 roughly corresponds to the elephant and System 2 the rider.

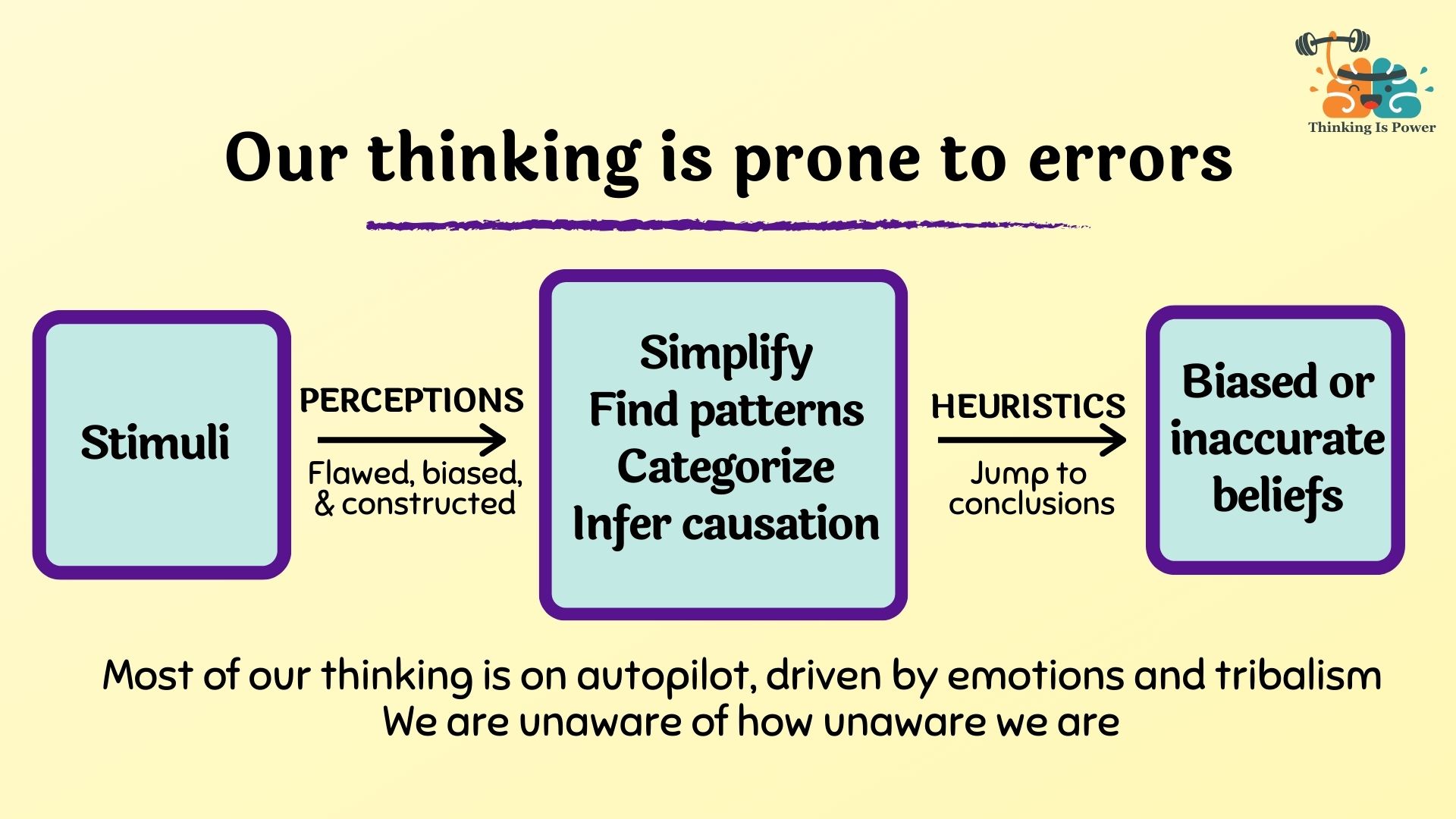

According to Kahneman, our brains have to make sense of infinite stimuli. So to save energy, we process information in two ways.

System 1 is fast and easy. Using experience and emotions, it searches for patterns, simplifies, and categorizes what our senses are perceiving. It relies on heuristics, or mental short-cuts, to make quick decisions with minimal effort. While the heuristics are usually good enough, they can lead to cognitive biases, or errors in thinking that cause us to misunderstand reality.

[Learn more: Guide to the Most Common Cognitive Biases and Heuristics]

Nevertheless, System 1 constructs a narrative consistent with what it expects, guessing and filling in gaps to reduce any uncertainty and ambiguity, then confidently jumps to a conclusion, unaware of how incomplete, flawed, and inaccurate it actually is.

System 2, on the other hand, is capable of reasoning and is generally more reliable, but is slow and requires effort, so it only turns on when System 1 is insufficient. Thus most of the time it lazily accepts System 1’s conclusion.

The point is, our riders (System 2) aren’t in charge…our intuitive and emotional elephants are (System 1).

And all of this is going on inside of our heads without our awareness.

The danger of trusting our intuitions

Our intuitions are based in our autopilot systems, which help us navigate our daily lives without much effort.

Evolutionarily speaking, these gut reactions are found in the oldest parts of our brains. System 1’s emotions and intuitions, such as the fight, flight, or freeze reactions, helped our ancestors survive by avoiding danger. Tribalism was similarly adaptive, as we depended on others in our small groups for safety and security.

However, what was adaptive as hunter-gatherers on the savanna is not adaptive in the modern age. Yet the emotional and tribal part of our brain never turns off, and guides much of our thinking, reactions, and decisions.

The point is, our intuitions aren’t wise….they’re tribal, emotional, and biased. Learn to recognize what your gut is telling you, but don’t blindly trust it.

The solution: Train the elephant

Our brains are capable of reasoning and logic. It doesn’t come naturally, though. And it takes work and practice. But assuming you don’t want to be wrong, it’s worth it!

Recall that our elephant (System 1) confidently jumps to conclusions, unaware of its own short-cuts and errors. Accepting these gut feelings requires very little effort, and the conclusions feel true, so most of the time we don’t even think to question them.

But cognitive laziness can lead us astray, often without us even knowing.

The solution is to engage your rider and train your elephant.

The first step is awareness. If you’ve never properly trained your elephant, chances are it’s wild and has been doing its own thing for most of your life. Be skeptical of your elephant’s intuitive conclusions and be willing to objectively analyze your gut.

The next step is metacognition, or being aware of your own thought processes. Essentially, think about how you are thinking. Recognize that your elephant has a tendency to be emotional and jump to conclusions. Learn to identify the short-cuts your brain is making and be on the lookout for biased thinking.

The final step is critical thinking, which is analyzing and evaluating evidence to decide what to believe or how to act. Be curious about the sources of your beliefs and be willing to question them. Think statistically, not emotionally. Learn to be comfortable with uncertainty. And avoid being overly confident…you might be wrong.

A warning: Don’t be a lawyer

While our rider is capable of objective, unbiased thinking, it can also be activated to protect and defend conclusions that are important to us and our tribe. The result isn’t just that we’re wrong…. we’re really wrong, yet really sure we’re right.

This is especially true for emotional beliefs that are part of our identity. Instead of logically following evidence to a conclusion, our rider acts like a lawyer, searching for evidence and constructing arguments to convince others that our elephant’s beliefs are true.

Importantly, intelligence doesn’t protect us. It can actually make it worse, as intelligent riders are better able to use their reasoning skills to find justifications for what the elephant wants to believe.

Our riders are capable of great things. So use their powers wisely. Don’t be a lawyer, be a judge.

The take-home message

We are more irrational than we think we are. Most of our thinking is on autopilot, which is fast but prone to errors. And though we’re often told to trust our gut, our intuitions are emotional, biased, and tribal… and often lead us astray.

But we’re not beholden to our ancient instincts. With a bit of effort and practice, our riders can learn to identify and correct our elephant’s bad habits. Just remember to slow down, remove emotions, and think critically.

Don’t trust your gut. Test it.

This is a massive “A-ha!!!” moment for me, because I’ve been fascinated by “the subconscious mind” and self-hypnosis, and Zen meditation, and I’ve been self-learning Psychology for decades. I have Autism and ADHD but I lived for more than 40 years before finding out that I have either of them. These two concepts: the Elephant & the Rider, and Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 – have now beautifully reconciled and amortised all of my prior studies in a gorgeous, beautiful whole. May I please beg you to look at the poem of the “Ten Bulls” from Zen Buddhism? I genuinely think that the author of that ancient poem figured out much of Haidt’s “Elephant & Rider” and Kahneman’s “System 1 & System 2”, all by themselves.

Thanks for the kind words! I’m SO glad to hear the piece resonated with you! And I will be sure to look up the “Ten Bulls.”

Best

Melanie

Excellent illustration of our behaviors relating to subconscious and conscious mind! Adorable!

Thanks! 🙂

This is very powerful Melanie. I now know where my laziness lives! Seriously though, I am finding your readings helpful in providing points of reference for a reflective journal I recently started. Nice work as always.

Hello! Thank you for the kind feedback.

Journaling has been on my “to do” list for a very long time, and I never get around to it. Best of luck with it! I hear great things.

Melanie