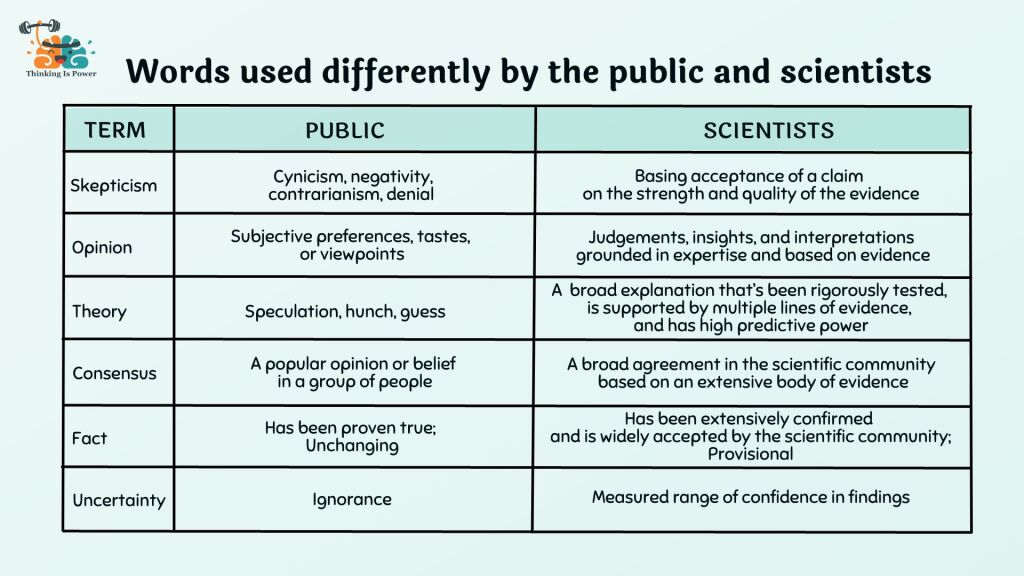

These six words have different meanings when scientists use them

The vocabulary of science can be quite confusing. Not only do scientists use highly technical jargon, they sometimes use the same words as the general public… but with different meanings. Unfortunately, the end result is that scientists can be misunderstood.

As an American who loves to travel, British English can be an unexpected source of confusion. For example, I wouldn’t recommend saying “fanny pack” to a Brit, as to them a “fanny” is slang for female genitalia. (The Brits say “bum bag.”) And if an American says they’re “pissed”, they mean they’re angry, while Brits mean they’re drunk. (And yes, these examples reveal my sophomoric sense of humor.)

We use language to communicate complex concepts, so it’s important to understand what someone means when they use a term. Here’s a brief list of six of the most commonly misunderstood words, and what scientists mean when they use them.

1. Skepticism: Skepticism is often associated with cynicism, contrarianism, negativity, or even denial. This is unfortunate, as scientific skepticism is simply insisting on evidence before accepting a claim… which is a good thing! Essentially, skepticism is basing your acceptance of a claim on the strength and quality of the evidence supporting it. And if the evidence changes, skeptics are willing to change their minds.

Importantly, skepticism and denial differ in their motivations and acceptance of evidence. Deniers don’t want to accept scientific conclusions that conflict with core beliefs, so they focus on small areas of uncertainty and demand impossibly high standards of evidence. Skeptics, on the other hand, are willing to follow the evidence wherever it leads.

2. Opinion: A common way non-scientists assume their views are equal to those of scientists is due to a misunderstanding of the word opinion. In everyday language, opinions are preferences, tastes, or viewpoints. They’re generally subjective in nature, and based on someone’s perspective, emotions, and biases. For example, in my opinion, cats are the best pets and peanut butter is the best flavor of ice cream. (I’m objectively right about both.)

On the other hand, scientific opinions are judgements or conclusions grounded in expertise and based on evidence. Experts possess specialized knowledge and experience, and can draw upon their deep understanding of a topic to provide informed insights, interpretations, and recommendations.

It can be tempting to deny a distasteful position because it’s “just an opinion”, but all opinions aren’t created equal. Expert opinions carry more weight and credibility due to their extensive knowledge.

3. Theory: Theory might win the prize for the most commonly misunderstood word in science. In everyday usage, a theory is a hunch. A guess. Pure speculation. For example, I have a theory about why my cat yells (sings?) at night — he’s calling on the spirits of his ancestors to free him from the captivity of his luxurious life.

But in science speak, a theory is exactly the opposite — it’s a broad explanation for a wide range of phenomena that’s supported by a vast amount of evidence. As science progresses and evidence accumulates, related ideas are combined into a single, clear, and powerful explanation. Theories form the basis of our scientific knowledge and are used by scientists to make predictions for further testing, and as such are continually subjected to scrutiny. Examples include gravitational theory, plate tectonic theory, evolutionary theory, cell theory, germ theory, and atomic theory. Understanding the natural world is the ultimate goal of science, and theories are about as close to the “truth” as we may ever get. So don’t be fooled when someone doubts science because “it’s just a theory.”

4. Consensus: In everyday language, a consensus refers to a general agreement or shared understanding within a group on a particular topic or issue. They’re often based on subjective perspectives, personal preferences, or prevailing opinions. For example, the consensus in my family is that I don’t look good with short hair. (They’re right.)

On the other hand, a scientific consensus represents a broad agreement within the scientific community on a specific topic. It reflects the collective judgment of experts and is based on an extensive body of evidence. Achieving consensus is a crucial aspect of the process of science, as it provides a foundation for further research and (hopefully) informs public policy decisions.

However – and this is the important distinction – science is not democratic, and a scientific consensus is not the result of groupthink. Scientists are motivated and incentivized to find errors and gaps in evidence and the resulting conclusions. Scientists don’t like to agree, and will only do so if there’s no sensible reason to disagree. The best explanation is the one that works the best and has survived repeated attempts at disproof, not the one that’s the most popular.

[Learn more: How to do your own research]

5. Fact: In common usage, “facts” offer what appears to be absolute proof. While the idea is alluring, especially in a world fraught with uncertainty, it’s not that simple. Science classes often don’t help, as many focus on having students memorize a textbook full of “facts.”

A scientific fact is an observation that has been extensively tested and confirmed, and is widely accepted by the scientific community. Facts are the building blocks of scientific knowledge upon which theories, laws, and models are constructed. Importantly, while “facts” can appear to be absolute truths, they’re not! Facts are subject to refinement, revision, or even overturning as new evidence or understanding emerges. Just ask Pluto.

6. Uncertainty: To the public, uncertainty means not knowing. To scientists, however, uncertainty is a measurement of our confidence in how well we know something.

It might seem strange to non-scientists, but scientists openly report findings with their level of certainty, ranging in from virtually certain (>99% probability) to exceptionally unlikely (less than 1% probability). There’s no such thing as absolute certainty in science. Scientific knowledge is always provisional and subject to revision with future findings. That said, as evidence accumulates we become less and less uncertain. Unfortunately, while the public often hears “scientists don’t know”, the reality is almost the exact opposite! Uncertainty isn’t an admission of ignorance, but an expression of how confident scientists are within a range that tightens as science progresses.

The bottom line is that science is never settled, but theories and consensus findings with extremely high certainty are as close as we’re going to get.

The Take-Home Message

The language of science can be confusing for non-scientists, but it needn’t be! Learn the vocabulary of the “locals” to prevent awkward exchanges and misunderstandings. (And remember, don’t say “fanny pack” in London.)

Learn more

Thoughtscapism: The Perils of Science Speak

Climate Communication: Communicating the Science of Climate Change

The Skeptic: Coming to Terms: The Words Believers, Skeptics, and the General Public Use Differently

Special thanks to Jon Guy and John Cook for their feedback.

Pingback: Mike’s News Jun 19 | Mike's News

Pingback: How to Speak Science – Neritam

It can be confusing that these important words have such different meanings. We need a way to distinguish the scientific meanings from the common meanings. Perhaps the best way to make that distinction is to put the word “scientific” in front of each of the six terms you present. For example “scientific skepticism”, “scientific consensus” etc

That’s a good suggestion!

Melanie

Hi Todd,

I am a social scientist and I have been a psychotherapist for a long time and am a researcher. I think the answer to your very real problem is that folks need to stay in their lane- those who don’t know science need to defer to those who do.

In Psychology, we have had to change the name of diagnoses several times because society uses our words in a pejorative manner. The lack of scientific literacy doesn’t need new terms, people need to become educated. All of science is being demonized. Whether from the climate change deniers or anti vaxxers, we are all lumped into this weird cabal funded group. Education is being threatened at its core.

I applaud this site for their work. Now, we just need people to become “uncertain” and practice critical thinking.

Pingback: Top des termes scientifiques les plus mécompris #1 : «Théorie» - Curioth