Our brains have to process an infinite amount of stimuli and make an endless number of decisions. So to save time and mental energy, our brains rely on heuristics, or short-cuts. Think of heuristics like guidelines, or rules of thumb: they’re good enough most of the time, but they can result in errors.

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking that interfere with how we reason, process information, and perceive reality. Basically, biases deviate our thinking away from objective reality and cause us to draw incorrect conclusions.

Biases and heuristics are part of our automatic or intuitive system of thinking, so they occur without our awareness. But because they impact nearly all of our thinking and decision making, familiarity with the most common errors is a great way to become a better critical thinker.

[Before reading about individual biases and heuristics, the following post is strongly recommended: Should you trust your intuition? The elephant and rider inside your mind]

A note on how to use this post: This page is a resource of the most common cognitive biases and heuristics, and is not intended to be read from top to bottom. Feel free to share the graphics to help others learn more about how to be better thinkers.

A very brief background

Cognitive biases and heuristics were first described by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the 1970s. While Tversky died in 1996, Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics for their work, which he later summarized in his best-selling (and must-read) book, Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Resources

Positive Psychology: Cognitive biases defined: 7 examples and resources

The Decision Lab: Cognitive biases

Effectivology: Cognitive biases: What they are and how the affect people

Big Think: 200 cognitive biases rule our everyday thinking. A new codex boils them down to 4. (Updated Codex)

MORE COMING SOON!!!

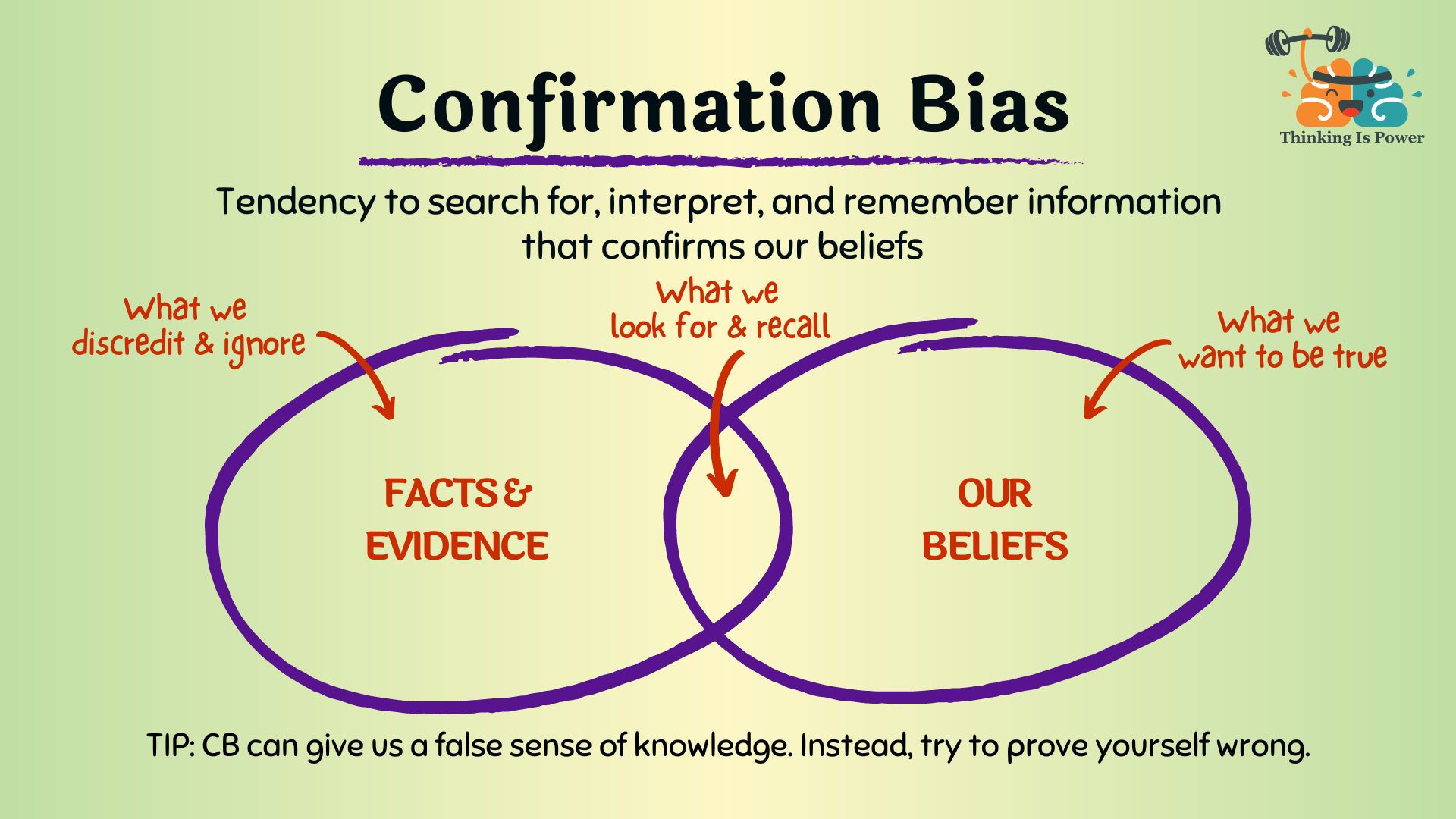

Confirmation Bias

Definition and explanation: Confirmation bias refers to the tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information that confirms our beliefs. In short, we prefer information that tells us we’re right…and we’re more likely to remember the hits and forget the misses.

In a world full of too much information, our brains need to take short-cuts. Unfortunately, some of these short-cuts can lead us astray. In the case of confirmation bias, the short-cut is: Does this piece of information support what I already think is true? If so, we assume there’s no need to question it.

Of all the biases, confirmation bias is the most powerful and pervasive, constantly filtering reality without our awareness to support our existing beliefs. It’s also self-reinforcing: because confirmation bias makes it seem like our beliefs are supported by evidence, we grow even more confident we’re right, and thus the more we filter and ignore information that would change our mind.

[Learn more: The person who lies to you the most…is you]

A prime example of confirmation bias plays out in our modern media environment, where we’re able to select news organizations and even the types of stories that validate our worldview. With the help of algorithms that learn our preferences, we can get trapped in filter bubbles, or personal information ecosystems, where we’re served more and more content that reaffirms our existing beliefs and protected from evidence that we’re wrong. (We really don’t like being wrong.) In essence, we assume our news feed is telling us about reality, when the reality is it’s telling us about us.

Confirmation bias is also one of the biggest reasons we fall for “fake news.” Why bother spending time and energy fact checking that viral video or news story or meme when it already fits with what you believe? It feels true, so it must be!

Another example of confirmation bias is the common (but mistaken) belief that the full moon impacts behavior. Indeed, the full moon is often blamed by nurses and doctors for an increase in hospital admissions and the police for an increase in crime. (It’s fun to note that the root of the words lunacy and lunatic come from the Latin luna for moon.) To be clear, there is no good evidence that the moon has any of these impacts.

So why then does this belief persist? Imagine a teacher who believes in the full moon effect. He notices his students seem to be a little rambunctious and thinks, “It must be a full moon.” If it is a full moon, he confirms – and probably becomes even more confident in – his belief. If it’s not a full moon, he quickly interprets their behavior differently or blames it on something else. And in the future, he’s much more likely to remember the examples that supported his belief and forget the others.

[Learn more: “Why do we still believe in ‘lunacy’ during a full moon?”]

How to overcome confirmation bias: Confirmation bias is amongst the most prevalent and influential of all the biases, so it’s important that critical thinkers try their best to reduce its impact.

Here are a few tips:

- Learn to recognize when you’re prone to confirmation bias, such as when a belief is tied to strong emotions and/or you’re confident you’re right. So slow down and don’t let your emotions guide your reasoning. And avoid overconfidence! The more certain you are that a belief is true, the less likely you are to question it.

- Be open to being wrong! The more tightly we hold our beliefs, the more contradictory evidence is viewed as a threat. But if you can’t change your mind with new evidence you’ll never be able to learn. Instead, separate your beliefs from your identity: You aren’t wrong, the belief is.

- Go one step further and search for evidence that would prove you wrong. In today’s information-saturated environment, if you’re looking for evidence that you’re right, you will find it. So instead, search for disconfirming evidence! If the belief is true it will withstand scrutiny.

Overconfidence effect

Definition and explanation: The overconfidence effect describes the tendency to overestimate our knowledge, ability, or performance. Think of this bias like a spotlight that illuminates our perceived expertise while shrouding our limitations in darkness.

If you’ve ever argued with someone who, despite being wrong, was absolutely convinced they were right, then you’ve experienced the overconfidence effect in action.

The overconfidence effect is amongst the most ubiquitous and pernicious of all biases. Nearly two thousand years ago, Greek philosopher Epictetus noted, “It’s impossible for a man to learn what he thinks he already knows.” And more recently, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman said overconfidence was so damaging that if he had a magic wand, he would eliminate it.

Our brains are constantly trying to understand the world around us, often taking short-cuts and jumping to conclusions along the way. When we learn something new, even if it’s incomplete or inaccurate, we fill in gaps with prior knowledge, assumptions, and biases.

Confirmation bias and the overconfidence effect make formidable teammates, resulting in a snowball effect: confirmation bias helps us find evidence, which leads to greater overconfidence in our position. This creates an illusion of knowledge, cluttering our minds with random facts that feel true, and leading to a false sense of expertise, in which we think we know more than we actually do.

The root of the overconfidence effect is a lack of self-awareness. When judging our competence, we often rely on internal cues — how well we think we understand something — rather than objective evidence or outside expertise. Ironically, this can be especially problematic for those with less knowledge, as they don’t know what they don’t know.

How to overcome the overconfidence effect: Recognizing the overconfidence effect and taking steps to mitigate it can help us learn, avoid unnecessary conflict, and make better decisions.

As with any bias, the first step to overcoming the overconfidence effect is awareness. Be mindful of your emotions, especially when an idea triggers a strong reaction. Positive emotions, like feeling right, can make us overly confident in our position even if it’s wrong. On the other hand, fearing being wrong can make us cling to our initial beliefs despite evidence to the contrary.

The antidote to the overconfidence effect is intellectual humility. Recognize that you might not know as much as you think, and that you might even be wrong. Most issues are complicated, and understanding them requires deep knowledge and expertise. If the answer seems simple and obvious to you, and yet somehow the vast majority of experts have “missed” it, consider it might be you who’s wrong.

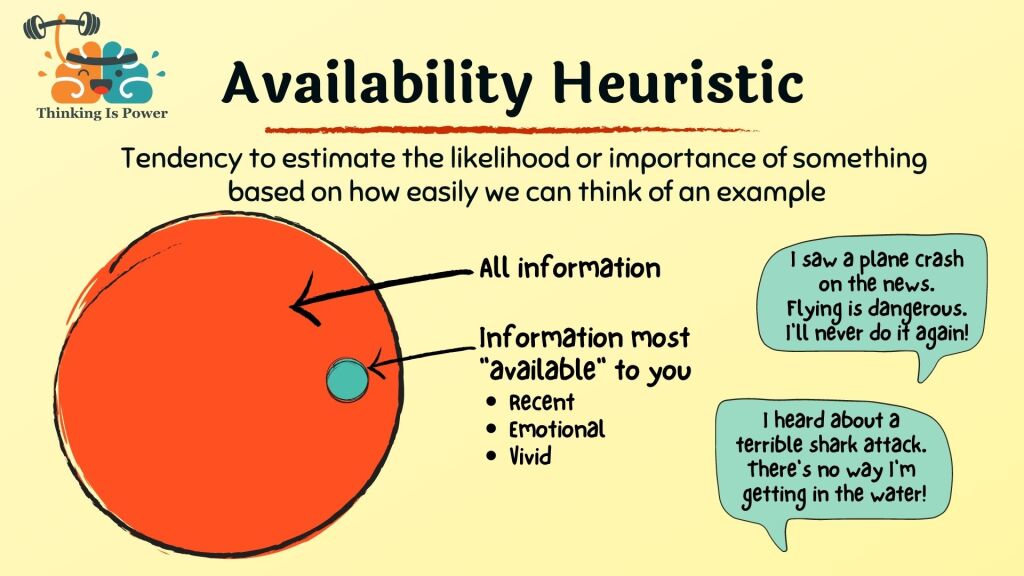

Availability Heuristic

Definition and explanation: The availability heuristic is a mental short-cut in which we estimate how likely or important something is based on how easily we can think of examples. However, because we are more likely to remember events that are recent, vivid, or emotional, we overestimate the likelihood of certain events and may make poor decisions.

Consider the following examples:

- You’re at the beach, thinking about going into the water, and images of shark attacks pop into your head. You sit and read a book instead.

- You recently saw a plane crash on the news, and you were already scared of flying, so you decide to drive on your next trip.

- You just watched a documentary about someone who won big on the slot machines, so you plan a trip to the casino. Someone has to win…it might as well be you!

- You’re worried about someone kidnapping your child because you saw news coverage of an attempted abduction. Thankfully, the child wasn’t harmed, but you don’t want to risk it. Today’s world is so much more dangerous than it was when you were young.

In all of these cases, you assumed something was likely because you could easily think of examples. Yet shark attacks are exceedingly rare, flying is orders of magnitude safer than driving, the chances of winning at the slots are miniscule, and there’s never been a safer time to be a kid. By confusing ease of recall with the truth, your brain misled you. And as a result you make poor decisions.

One of the biggest influences on our perception of risk is news coverage. By definition, the news covers events that are new and noteworthy, and not necessarily things that are common. News reports of murders and horrible crimes (or shark attacks and plane crashes) can result in us thinking these events are more common than they really are.

How to overcome the availability heuristic: The first step in overcoming any heuristic is awareness. Remember, the goal is to determine how likely something is in order to make better decisions. Short-cuts help us think fast, but they aren’t always reliable.

So slow down your thinking and don’t assume the first thing that pops into your head is representative of reality. Try to identify the stories your brain is using as evidence, and notice any emotions connected to them. Then if possible, use statistics instead!

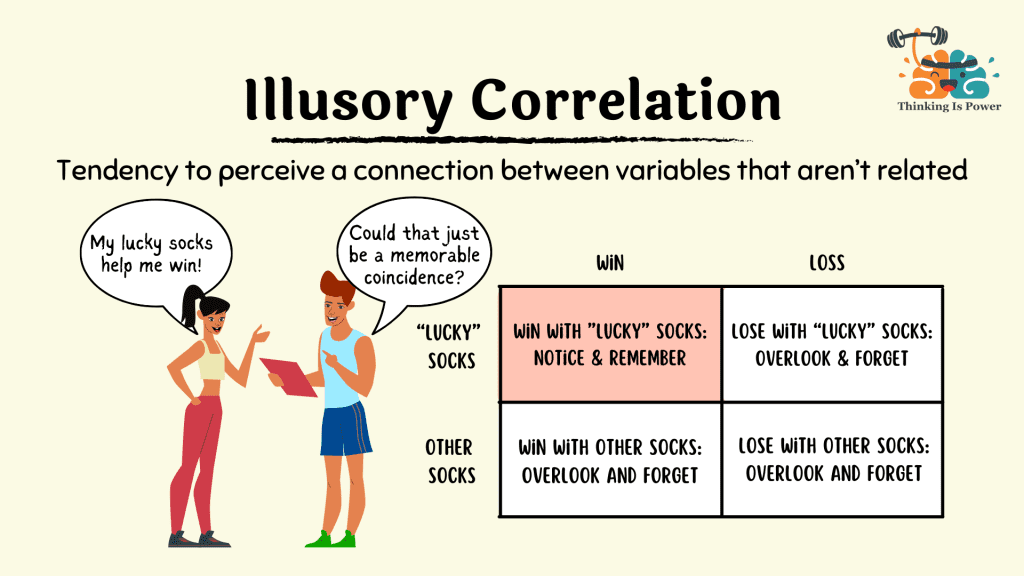

Illusory correlation

Definition and explanation: Illusory correlation describes our tendency to perceive a connection between variables that are not necessarily related.

Our brains are constantly searching for patterns to help us make sense of the world, but sometimes the associations we detect aren’t real. Essentially, illusory correlation is a mental shortcut gone wrong, where we mistake a coincidence for cause and effect.

Two other biases contribute to illusory correlation: confirmation bias and availability heuristic. Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, and remember information that confirms our beliefs. Availability heuristic is a mental shortcut in which we estimate how likely or important something is based on how easily we can think of examples.

Because vivid events stand out, we’re more likely to notice and remember them. Once we’ve detected a pattern, we unknowingly continue searching for evidence that confirms our belief. This not only leads to false conclusions, it often results in overconfidence as it tricks our brains into thinking we’ve found a strong connection (we have “evidence”, after all!) when the link is actually weak or nonexistent.

Illusory correlations are quite common and show up in many aspects of our daily lives.

One such example is superstitions. Imagine an athlete wins a big game while wearing mismatched socks. They might credit the socks for their success, convinced they’re “lucky.” Their brains then tend to latch onto the vivid events (winning a game with the socks) and forget the ordinary events (winning without the socks, or losing with the socks), confirming their belief of a cause-and-effect relationship, when in reality it’s just a coincidence.

[Learn more: Believing in Magic: The Psychology of Superstition by Stuart Vyse]

Another example is stereotypes. Imagine seeing a few loud tourists at the airport. Since the loud tourists stand out, they’re easier to remember than the more numerous quiet tourists you encounter. Once we have a stereotype about a group, we tend to notice situations that confirm the stereotype. With availability heuristic and confirmation bias working together, our brains create and maintain a false connection, making it seem like this behavior is linked to the entire group.

As a last example, illusory correlation can also play a role in misunderstanding health issues. Imagine breaking out after eating a particular food. Because an acne breakout is a memorable event, it’s easier to recall than the many times you ate that food without any problems. If you already suspect that food might cause breakouts, you’ll be more likely to focus on this one experience and forget the uneventful times. This can lead to mistakenly believing the food is always a trigger, when in reality it could be a coincidence or another factor causing the breakout.

How to identify and overcome illusory correlation: While identifying real associations can help us understand the world better, falling for illusory correlations can lead us astray. The trick is being able to distinguish between the two and not be fooled by our selective perception and memory.

Our brains perceive illusory correlations because they tend to notice “hits”, the more memorable events that seem to support a connection, and overlook “misses”, the uneventful or even contradictory “non-events” that don’t. So to determine if an association is real, we must consider all data: the hits and the misses.

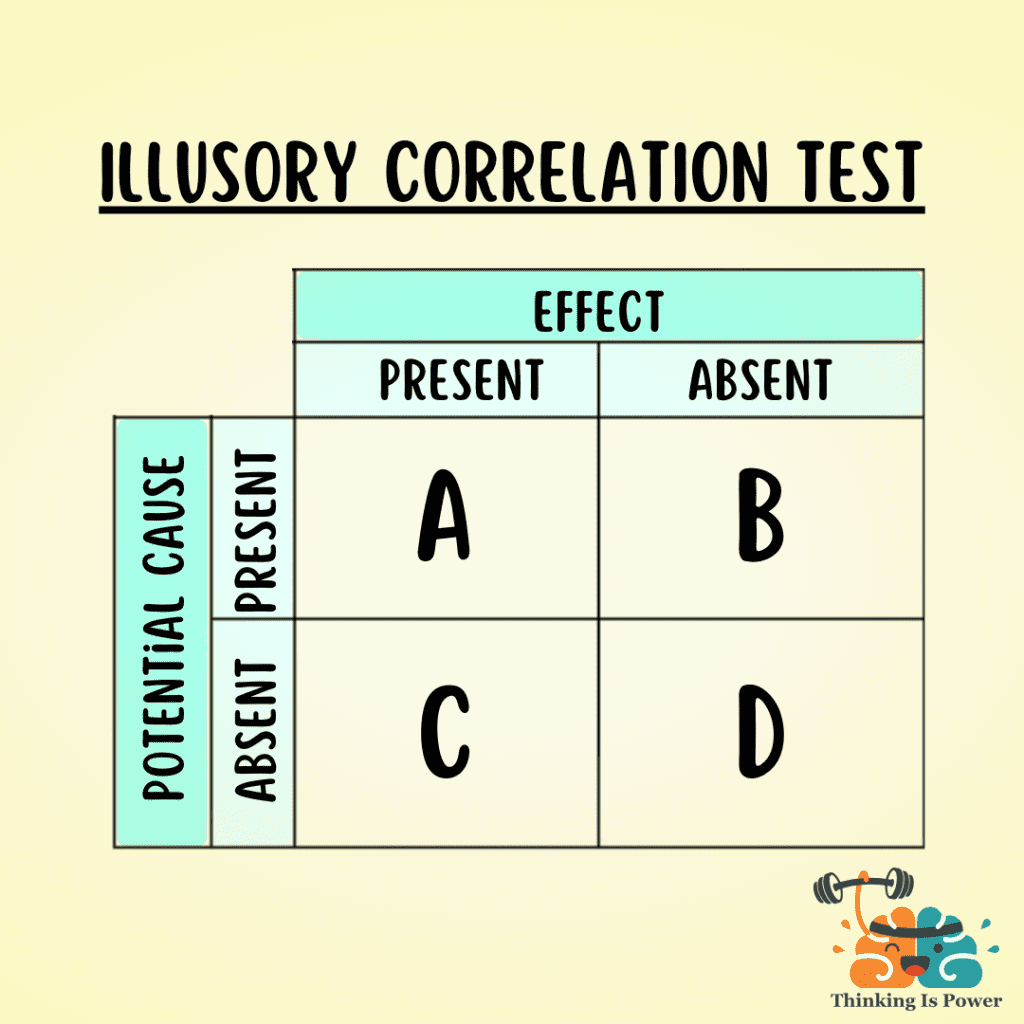

Contingency tables can help us sort real patterns from coincidences, as they encourage us to consider those events that might otherwise be invisible to us. To use the table, first clearly identify the potential cause and effect, then fill in and examine all four cells.

As an example, let’s consider the superstitious belief that Friday the 13th is unlucky. The potential cause is Friday the 13th and the effect is bad luck.

- Cell A (“hits”): Represents the Friday the 13ths in which you had bad luck. These events are more noticeable and memorable, and result in an illusory correlation.

- Cell B (“misses”): Represents the instances in which you didn’t have bad luck on a Friday the 13th. It’s easy to overlook all the “non-events” on Friday the 13th. Without the effect present, we often don’t consider the potential cause.

- Cell C (“misses”): Represents the times in which you had bad luck, but it wasn’t a Friday the 13th. These instances are easily dismissed because they don’t fit the rule.

- Cell D (“misses”): Represents the times you didn’t have bad luck and it wasn’t a Friday the 13th. Nothing here stands out, so these instances are easily overlooked.

As we can see from this exercise, the belief that Friday the 13th is unlucky is due to our tendency to jump to conclusions based on memorable coincidences. By including the non-events that are easily overlooked and forgotten (i.e., the “misses”), we can recognize this superstition for what it is: an illusory correlation. In short, reducing the influence of illusory correlations on our thinking and decision-making requires awareness, skepticism, and critical thinking. When you find yourself noticing a connection, take a step back and question it! Consider the hits and the misses, and be open to the possibility that it’s just a coincidence.

Ingroup-Outgroup Bias

Definition and explanation: The ingroup-outgroup bias refers to our tendency to favor members of our own group over those from other groups. This bias fosters an “us vs. them” mentality, which can lead to social division, prejudice, discrimination, and even conflict between groups.

Throughout most of our history, humans lived in small, tight-knit groups. These groups provided access to shared resources, protection against predators, and defense against rivals, increasing the chances for survival. Individuals who didn’t cooperate or who weren’t loyal to the group faced ostracism and the unfortunate reality of attempting to survive on their own.

This evolutionary history gave rise to the ingroup-outgroup bias. Our brains are wired to readily categorize individuals as part of our group (our ingroup) or as outsiders (the outgroup). Today’s groups can be organized around any number of factors, such as nationality, religion, political ideology, or even shared interests (like sports or hobbies). While these social identities provide us with a sense of belonging, purpose, and connection, our preference “us” can lead to negative attitudes and behaviors towards “them”.

Henri Tajfel and the Minimal Group Paradigm: As a Jewish man living in Poland in the early 20th century, Henri Tajfel witnessed firsthand the devastating effects of prejudice and discrimination. During World War II he served in the French army, then spent several years in German prisoner-of-war camps. While he survived, most of his friends and family were killed in the Holocaust.

After the war, Tajfel became a social psychologist to better understand how our social identities could lead to such intense conflicts and violence. In one fascinating study, he and his colleagues sought to determine the minimal conditions necessary for individuals to show favoritism towards their group members. Participants were assigned to groups based on their preferences for certain paintings then asked to divide money between members of their group and the other group. Not only did participants award more money to ingroup members, they took less money if it meant maximizing the difference between their group and the other group! However, the cherry on top was that Tajfel had actually assigned participants to groups randomly, not based on their artistic preferences!

Tajfel had planned to gradually introduce group distinctions to determine when discriminatory behavior emerged, but was surprised to find out that participants exhibited in-group favoritism and out-group discrimination with even the most minimal group differences.

Tajfel’s findings demonstrated that simply categorizing people into groups, even based on arbitrary or meaningless traits, was enough to trigger ingroup favoritism and outgroup hostility.

Now imagine how this bias might manifest between groups with more meaningful differences.

What’s the harm: The ingroup-outgroup bias, with its tendency to favor one’s own group, can have far-reaching consequences for individuals and society. This bias can lead to unfair exclusion and mistreatment of outgroup members, fueling hostility and tension between groups.

We often negatively stereotype outgroup members, perceiving them as more alike than they truly are. This outgroup homogeneity effect can lead to harmful generalizations, such as labeling entire nationalities as lazy, hostile, or untrustworthy. In extreme cases, this bias can even lead to dehumanization, where outgroup members are viewed as less than human, justifying mistreatment, exclusion, or violence.

Furthermore, we often apply a moral double standard, judging ingroup members more leniently than outgroup members for similar behaviors. When someone from our ingroup misbehaves, we may excuse or downplay their actions, while we’re more likely to judge an outgroup member harshly for the same offense.

How to overcome the ingroup-outgroup bias: The ingroup-outgroup bias, while adaptive in our evolutionary past, can lead to prejudice, discrimination, and social conflict in today’s world. Fortunately, we can take steps to mitigate its harmful effects and build more just and inclusive societies.

A crucial first step is education and awareness. By understanding how biases operate, we can challenge and overcome them. Additionally, positive intergroup contact can foster empathy, understanding, and respect between different groups.

Ultimately, we can reframe our identities to be broader and more inclusive. We’re all human, after all.

Framing effect

Definition and explanation: The framing effect refers to how our thoughts and decisions can be influenced by the way information is presented, or “framed”. Essentially, this bias helps us understand the power of language on our perception and memory.

While there are different types of framing, the most common are positive and negative. Positive framing emphasizes potential gains or benefits, while negative framing highlights the potential losses or drawbacks. Both are different ways to spin identical information to influence a desired response.

Imagine a yogurt that advertises either “20% fat content” (negative frame) or “80% fat free” (positive frame). While both statements are accurate, which yogurt you choose? Similarly, would you be more likely to opt for a surgery with a “90% success rate” or a “10% failure”?

The framing effect is commonly exploited by those seeking to influence our behaviors. For example, advertisers highlight product benefits and present prices as discounts. Politicians frame issues that favor a certain viewpoint and emphasize gains or losses to influence public opinion on policies. And propagandists carefully select and spin information to shape how people perceive issues.

Further, the way information is presented can impact not just our decisions but also our memories. In one classic example, Elizabeth Loftus demonstrated how word choice can alter our recollection of events. When asked, “How fast was the car going when it hit the other car?”, participants estimated lower speeds than those asked, “How fast was the car going when it smashed into the other car?” One subtle word change influenced how participants remembered the crash. Now imagine how many of your memories have been altered by later information. It’s a humbling thought.

How to overcome the framing effect: The framing effect demonstrates how carefully chosen words can shape how we interpret information, impacting how we think, feel, and remember. And like all biases, the most important first step to protect yourself from the influence of framing is awareness.

To counter the framing effect, focus on substance over style. Dig down past how information is presented to consider the core of the message. How else might you rephrase the wording? Can you spin the words to produce the opposite connotation? How do these different framings impact your perspective?

The bottom line is, making wiser decisions requires us to understand information, so don’t let someone’s framing alter your view of reality and lead you astray.

Truth bias

AKA Truth-Default Theory

Definition and explanation: The truth bias describes our tendency to believe information, regardless of how true it is. This bias can be sneaky, as our natural inclination to believe can cause us to fall for things that just aren’t true.

In general, it makes sense not to question everything. Most of the time people are honest, and it takes a lot more mental energy to be skeptical than it does to believe. Imagine how difficult (and time consuming) everything would be if you had to question every single thing you heard or saw!

However, we all know that sometimes people aren’t truthful. Sometimes they stretch it a bit. Leave out important details. And sometimes they’re just plain lying. So it’s crucial to know when to be skeptical and search for confirmation.

In the past, our believing brains were only exposed to what we were told by members of our small tribes, many of whom we were related to. Today our brains swim in fake news, propaganda, hoaxes, pseudoscience, conspiracy theories, and so on. That’s a lot of information to question and think critically about… and so, too often, we don’t. As a result, our brains run a very high risk of being polluted with falsehoods.

Unfortunately, many of us like to think that we’re too smart to fall for a falsehood. We assume our beliefs were formed by following and evaluating evidence. The end result is that we can be wrong, but be confident that we’re right.

We don’t always believe what we hear, of course, and there are many other factors that can impact our acceptance of claims. One of the most important is simply trust. The problem is, we don’t always trust the source that’s the most credible, but the one that we identify with and/or the one that appeals to our emotions. There’s a reason scammers exploit these weaknesses!

How to overcome the truth bias: As with most mental shortcuts, awareness is key! Recognize that the truth bias is real, that we’re all prone to it, and that it can influence our judgment and decision making.

With this in mind, one of the best things we can do is to not expose ourselves to potential falsehoods in the first place! Cleanse your media diet and follow reliable sources as much as possible. Remember, we are all susceptible to believing falsehoods, and it’s dangerous to think otherwise.

As always, it’s essential to properly place our trust. We have a tendency to trust our in-group members, but they might not be the best source. Organizations and experts with a track record of honesty and accuracy are more likely to be trustworthy.

The goal isn’t to be overly suspicious, but to strike a healthy balance between trust and skepticism, especially in situations where the accuracy of information is critical or there are good reasons to not trust the source.

In short: trust, but verify. While it’s generally safe (and easier) to trust others, be prepared to look for independent confirmation and supporting evidence.

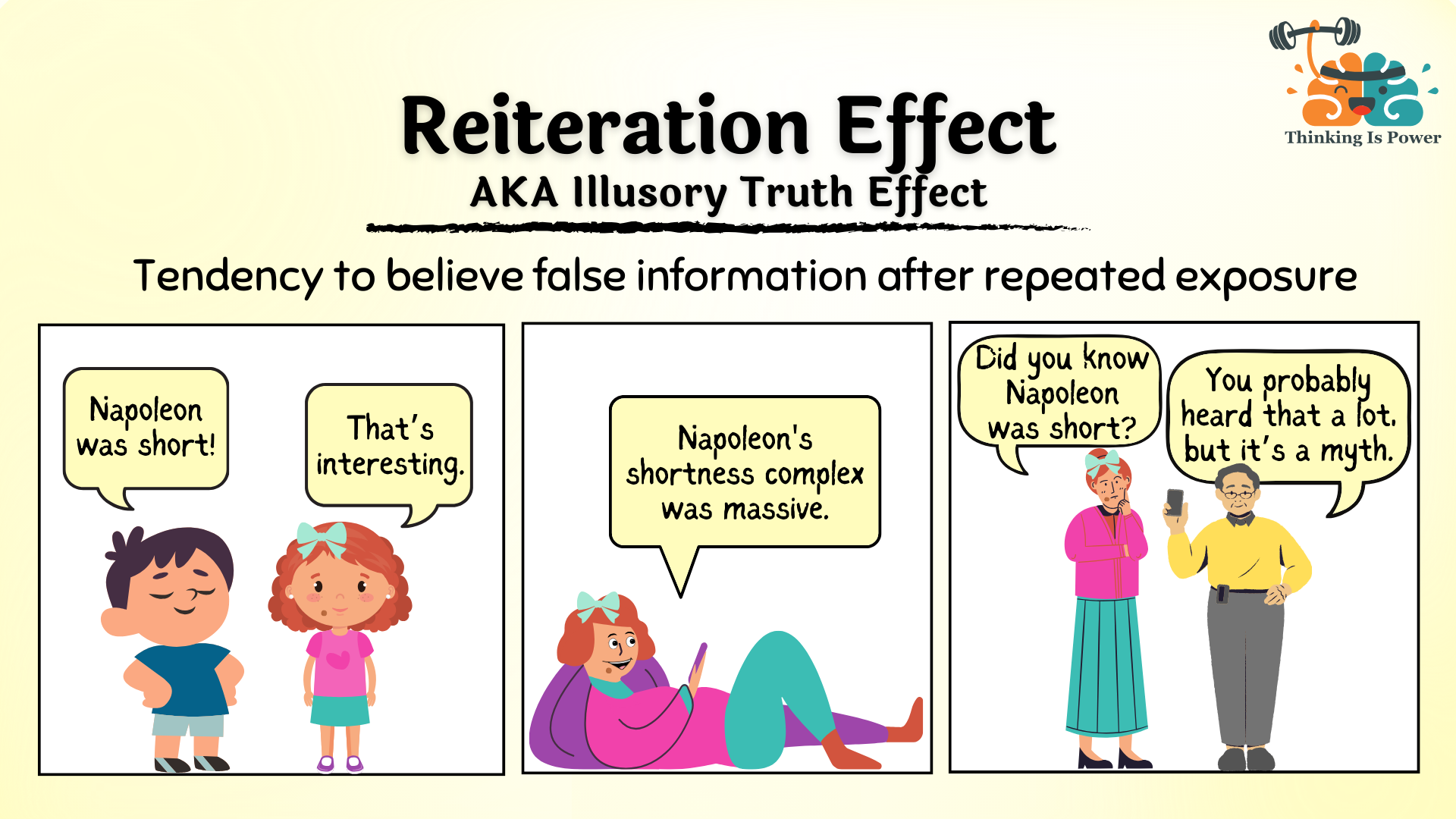

REITERATION EFFECT/ILLUSORY TRUTH EFFECT

AKA Illusory Truth Effect

Definition and explanation: The reiteration effect, or the illusory truth effect, is the tendency for people to believe false information after repeated exposure. Essentially, when determining if something is true, our brains rely on the information’s familiarity, which increases with repetition.

Imagine hearing a rumor for the first time. At first, you’re not sure if it’s true (it’s not!), but it plants a tiny seed in your mind. You hear it again later. And again the next day. Every time you hear the rumor repeated the belief is watered and fertilized. Without realizing it, you’re convinced the rumor is true, despite the lack of evidence, simply because you heard it so many times.

The reiteration effect occurs due to our brain’s reliance on shortcuts, such as familiarity, as a heuristic for truth. When information is encountered repeatedly, it becomes more accessible in our memory. Even more, every time we hear information it’s easier to process. The result is that we’re more likely to accept information the more we’ve encountered it.

But it gets worse: even if we initially know a claim is false, hearing it repeatedly can mess with our heads. Due to processing fluency, our brains can get so used to hearing a falsehood that it starts to feel true, despite our better judgment.

This phenomenon has serious implications for the spread of misinformation, decision-making, and political persuasion. (In “Thinking, Fast and Slow”, Daniel Kahneman noted, “A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth. Authoritarian institutions and marketers have always known this fact.”)

Social media platforms can amplify false claims, as they generate high engagement and shares. This is exacerbated in echo chambers, in which users are surrounded by individuals and content that reinforce their existing beliefs and biases.

Advertisers repeat exaggerated claims to convince consumers to buy their products despite the lack of evidence. And politicians infamously echo their slogans and talking points to drill their views of themselves (and their opponents) into our brains. Over time, the familiar phrases and sound bites start to feel true to the point that we don’t even think to question them.

The reiteration effect is a prime example of how easily our brains can fool us. Repeated messages can shape our beliefs and decisions, whether they’re true or not, so understanding how this sneaky effect works is key to seeing through the spin and making more informed choices.

How to overcome the reiteration effect: Understanding the reiteration effect and why we fall for it can help us navigate a misinformation-saturated world with greater discernment and accuracy.

Like all biases and heuristics, awareness and skepticism are the first steps. It’s difficult to question and correct a falsehood after hearing it repeatedly, so do your brain a favor and try to avoid exposure in the first place! Cleanse your media feeds of known misinformation purveyors and get into the habit of questioning and fact checking claims before accepting them. But don’t stop there: also learn to question the source and validity of information that’s been encountered repeatedly.

In short, it’s important to keep in mind that just because you’ve heard something repeated a million times doesn’t make it true! So take a step back and ask yourself: where did this information come from, and is there any evidence to support it?

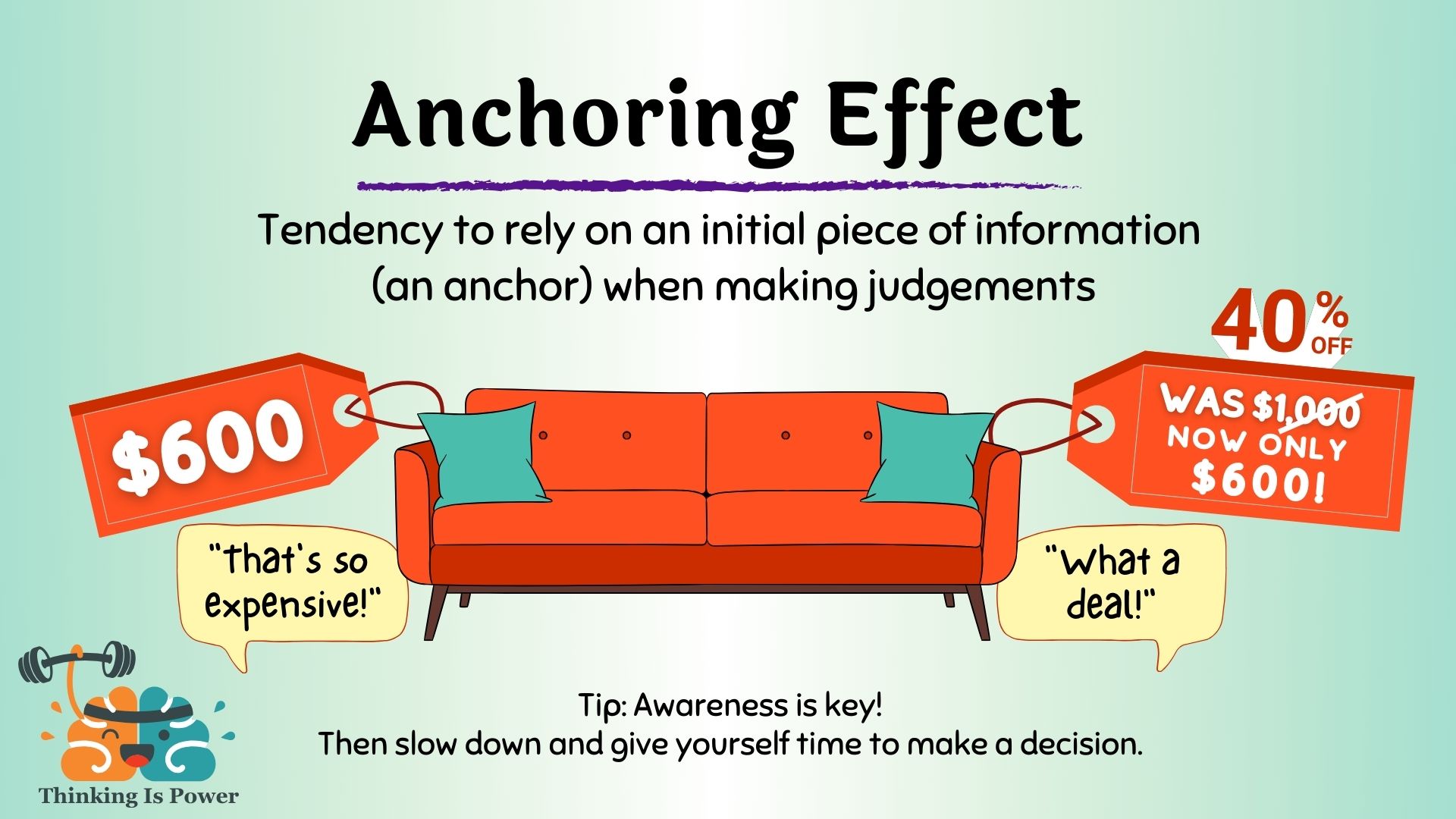

anchoring effect

Written by Jon Guy

AKA: Anchoring heuristic

Definition and explanation: The anchoring effect refers to our tendency to “anchor” to the first piece of information we learn about something, and form our beliefs about that thing based on the anchor. Newer information isn’t evaluated objectively, but, rather, through the lens of the anchor. The anchoring effect is an extremely common cognitive bias, and one that can interfere with our abilities to make good decisions and objectively understand reality. Therefore, understanding the anchoring effect can save us time, money, and improve the quality of our thinking.

The anchoring effect occurs when we unwittingly cling to the first bit of information we get about something. However, if we’re not careful, anchoring can result in poor decisions that we may regret. For example, you discover that the new car you’d like to purchase costs an average of $25,500 (the anchor). So you take a trip to a local dealership, and the salesperson offers to sell you the vehicle for $24,000. “What an amazing deal,” you think, as you drive off the lot in your new car. Later you learn that several other dealerships around town are selling the same vehicle for $23,000! Since you were anchored to the original $25,500, anything less sounded like a good deal, and that anchor kept you from pursuing prices at other local dealerships.

But as I mentioned earlier, anchoring can be tricky. Not only does it affect many of our decisions, it can even affect decisions that are made for us. For instance, if your doctor anchors to the first symptoms you report about an illness, she might misdiagnose you without pursuing other possible explanations. Or, if you’re waiting on a decision from a jury on an insurance settlement case, their decision on how much to award you might be influenced by a strategically placed anchor.

Most people agree that taking care of our health is one of the more important goals we pursue throughout our lives. But let’s say your grandparents and great-grandparents were all very long-lived. You might anchor to their longevity as an expectation of how long you will live, without taking into consideration that they might have lived much more healthy and active lifestyles than you do. Therefore, by anchoring to one piece of information (how long they lived) and ignoring other, more important pieces of information (how they took care of themselves), you could wind up neglecting your own health by eating poorly or exercising infrequently.

The anchoring effect is so powerful that the anchor doesn’t even have to be relevant to the thing we’re making a decision about! For example, researchers have shown that putting an expensive car on a restaurant menu actually resulted in people spending more money while dining there. Other researchers have shown that by simply asking people the last two digits of their social security number and then showing them a list of products, those whose last two digits were higher were willing to pay more for the products than those whose digits were lower.

How to overcome the anchoring effect: The anchoring effect is an extremely pervasive bias, and even contributes to other biases. Moreover, since anchoring happens outside of our conscious awareness, interrupting the process can be rather challenging. Therefore, it is important to understand the effects of anchoring, so that we might stand a chance of overcoming them.

For example, thinking long and hard about an important decision always sounds like a good idea, right? Intuitively, this makes sense. However, if we’re merely thinking deeply about the anchor, we’re just amplifying its effects, and probably digging ourselves even deeper into our biases.

Fortunately, there are some strategies we can use to combat, if not completely overcome, the anchoring effect, such as by practicing metacognition. We are cognitive misers, which means overcoming our biases requires us to maximize metacognition; an awareness and understanding of our own thought processes. Or as I like to call it, thinking about thinking.

Another strategy we can employ is to try to consider alternative options. If you see t-shirts on sale for 3 for $10, consider that you may only need one, or that you might not need any! Anything you can do to interrupt the decision-making process can help to slow down your thinking and give you the time you need to make a better decision.

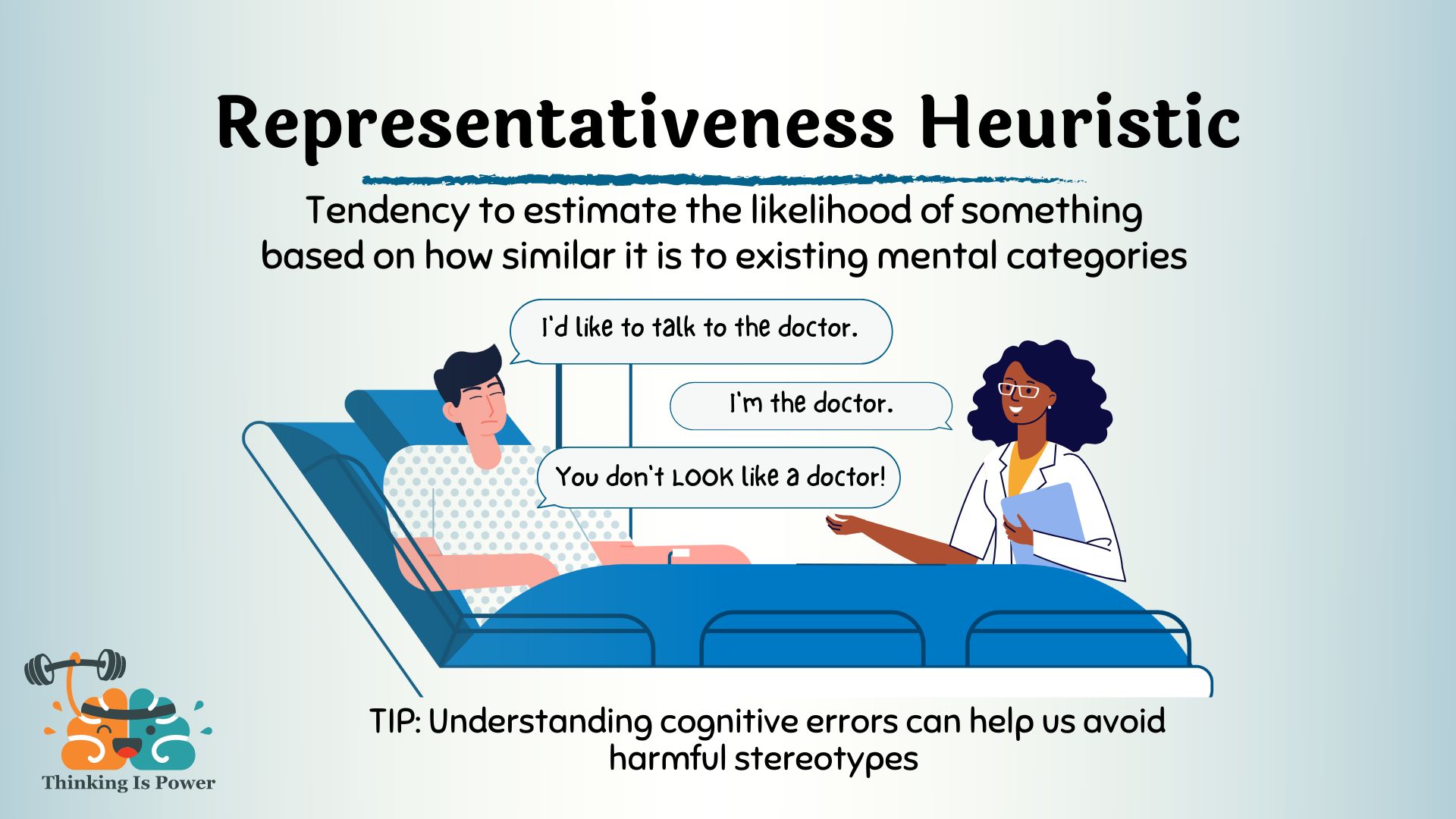

Representativeness heuristic

Written by Jon Guy

Definition and explanation: The representativeness heuristic doesn’t exactly flow easily off the tongue. Nonetheless, this heuristic is well worth our attention. Like all heuristics, the representativeness heuristic is a mental shortcut our brains take to preserve its limited resources, in this case to make quick judgments about the likelihood of something based on how similar it is to existing mental categories.

The representativeness heuristic is an error of reasoning that occurs when we make generalizations based on our mental models of reality. To use a classic example, let’s say I told you that Mary is a quiet, shy introvert who’s not very interested in getting to know people and is also very detail oriented. Based on this description, is it more likely that Mary is a librarian or a mechanic? Our gut tells us that Mary is much more likely to be a librarian because her characteristics sound more representative of our mental models of librarians.

But the representativeness heuristic doesn’t just apply to our perception of people. For example, if you saw a frog with bright colors, you might assume that it’s poisonous based on your mental model of what poisonous frogs look like. Or, imagine shopping for a new phone case. If you find one that looks thick and durable, and you assume that it will provide good protection because of your prior mental model about what durability looks like.

The reason we might assume the frog is poisonous is because most of us have a mental construct of what poisonous animals look like, and a colorful frog fits the bill. Likewise, our mental constructs about what constitutes durability might lead us to believe that a thick case means that it’s durable. In either situation, our default assumption is based on our prior mental models, and questioning these models requires deeper thinking. Without further evidence, we cannot know whether the frog is poisonous or the phone case is durable.

Perhaps the best example of the representativeness heuristic is stereotyping. Stereotyping occurs when we have a mental model of a specific class of people, and we make judgments about all people within that class based on our mental construct. Just as we assumed that “colorful amphibian” means “poisonous animal,” we make similar assumptions about classes of people. For instance, we might assume that all Indians enjoy spicy foods, or that all Native Americans are highly spiritual, or that all rich people are snobs, or that all homeless people are drug addicts and alcoholics. However, in each of these incidents, our mental models will be wrong much of the time, and so it is up to us to think critically about how our brains misinterpret reality.

Heuristics are short-cuts our brains take to save energy. Importantly, they aren’t necessarily bad and don’t always lead us astray. Additionally, our brains categorize things (i.e. people, places, events, objects, etc) based on our previous experiences so we know what to expect and how to react when we encounter something new in that category. If we didn’t categorize things, every new thing we encountered would overwhelm us! So, while the representativeness heuristic can cause us to misconstrue reality, it’s also a valuable tool that helps us navigate our daily lives. Rather than trying to determine if every moving car is potentially dangerous, we draw on our mental models of moving vehicles, and treat them all with caution. Likewise, if a grizzly bear was running our way, we’d know we were in trouble, but if a tumbleweed was speeding towards us, we’d know we have nothing to fear.

Even though the representativeness heuristic can be a useful tool, it’s still important for us to maintain our skepticism and practice our critical thinking skills. While categorizing things assists our brains in reducing its cognitive load, we need to remember that even our mental constructs might be wrong, and understand how easily stereotypes can become prejudices. Moreover, categorizing limits our ability to see similarities and differences between different things, and, when we pay too much attention to specific boundaries, we further limit our ability to see the whole.

As the foregoing examples show, the representativeness heuristic can affect our judgment in both trivial and nontrivial ways. It’s not that big of a deal to incorrectly assume that the guy wearing a suit is a businessman, when he’s actually a plumber headed to a costume party. However, judging one individual based on a stereotypical example is a major driver of racism, sexism, classism, and even speciesism. Therefore, becoming better educated about our mental shortcomings goes a long way toward making the world a better place.

How to avoid the representativeness heuristic: Biases are part of human nature, and oftentimes serve valuable purposes. As such, completely avoiding the representativeness heuristic is unlikely, and undesirable. However, there are several things we can do to minimize the number of times we fall for it, as well as reduce its effects when we inevitably slip up.

Awareness of our biases is bias kryptonite, so understanding when we’re vulnerable, sharing what you’ve learned about it with others, and developing critical thinking skills are excellent ways to avoid this bias.

Finally, education can help us combat cognitive biases. Learning formal logic, becoming a better statistical thinker, or studying other errors of human cognition are all great ways to minimize our biases, become better thinkers, and perceive reality on reality’s terms.

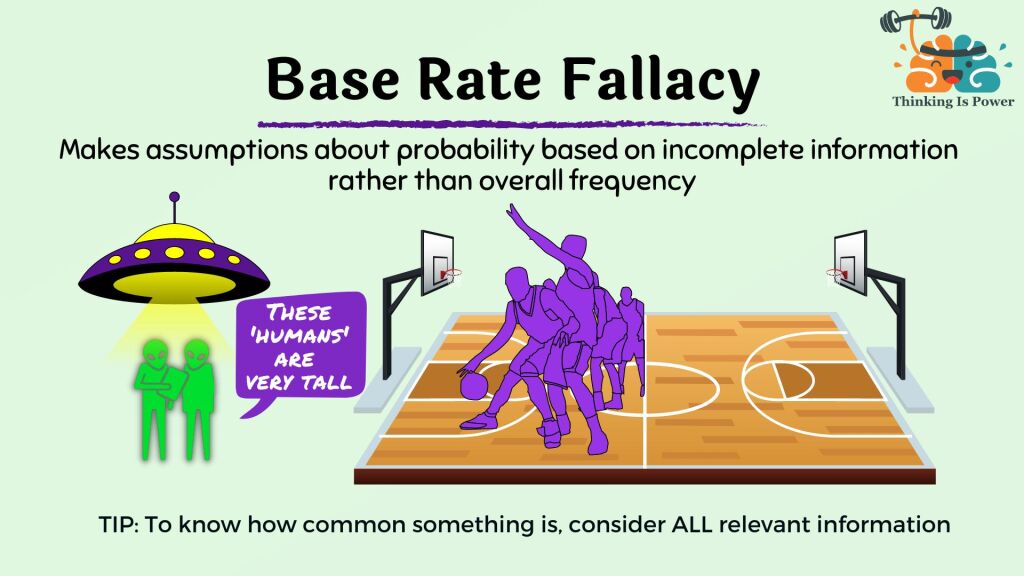

Base Rate Fallacy

Written by Jon Guy

AKA: Base rate neglect and base rate bias

Definition and explanation: The base rate fallacy occurs when we draw conclusions about probability from limited information, rather than from statistical data. Oftentimes, thinking statistically is a difficult undertaking, and it isn’t something we do intuitively. But to make wise decisions, sometimes we need to understand how likely something is, so let’s explore what the base rate fallacy is and discuss some strategies for avoiding it.

A base rate is the likelihood that an event will occur, or the proportion of individuals in a population that share certain characteristics. Unfortunately, instead of judging probabilities by looking at base rates, we often rely heavily on personal experiences or vivid stories. Readers might be reminded of the availability heuristic, a bias which causes us to estimate the likelihood or importance of something based on how readily similar examples come to mind. By contrast, the base rate fallacy occurs when we weigh the probability of something using only a small sample size, without considering all of the relevant information.

For example, if everyone you spoke with in your neighborhood voted for candidate X, you may assume that candidate X would win the election by a landslide. But your neighborhood—or even region—is only part of a much larger population of voters. By ignoring the base rate of all voters, or the overall popularity of candidate X, you’ve committed the base rate fallacy.

Concerningly, people often commit this error when it comes to matters of health. For example, a headline that reads “Among those who died from infection, 50% were vaccinated” makes it seem like those who are vaccinated are just as likely to die as those who aren’t. Imagine, though, that the population is 100 individuals, 99% of which are vaccinated. Two people die — the individual who wasn’t vaccinated and one of those who was. The headline is technically accurate, but wildly misleading, as the death rate among the unvaccinated is 100%.

The base rate fallacy shows up in many aspects of our lives, and sometimes carries severe consequences. For example, doctors might order expensive or invasive tests based on a person’s symptoms, even if the base rate of the disease they’re testing for is low, which could lead to unnecessary costs and risks. Or, judges and juries may convict someone based on circumstantial or anecdotal evidence, even if prior probability of guilt is low, leading to wrongful convictions and miscarriages of justice. Or, investors may back a specific company based on recent performance, even if the likelihood of success is low, leading to poor financial decisions and financial losses.

As the saying goes, if you hear hooves, think horses, not zebras. (Unless you’re in Africa.)

How to overcome the base rate fallacy: The base rate fallacy, like other thinking errors, occurs when we’re blind to information we don’t have, and as a result, we place greater emphasis on the information we do have. Thus, one way to avoid this fallacy is to apply the “rule of total evidence,” which requires us to consider all relevant information when forming an opinion. Essentially, we want to make visible the information we wouldn’t otherwise consider and then evaluate all of the information before forming judgments. As you can imagine, this is far easier said than done.

Applying the rule of total evidence to some of our examples from above; doctors could use diagnostic algorithms that consider a patient’s symptoms alongside the base rate of specific diseases within the population; judges and juries could receive instructions to consider the base rate of guilt when evaluating evidence and testimony; or investors could use diversification strategies to consider both the performance of specific companies along with the historical performance of the market as a whole.

As with all biases, awareness is key. Remember that we can easily be fooled by our personal experiences or emotional stories into thinking something is more common than it actually is. And by remembering to consider base rates, we can improve our thinking skills and our ability to make wiser decisions.

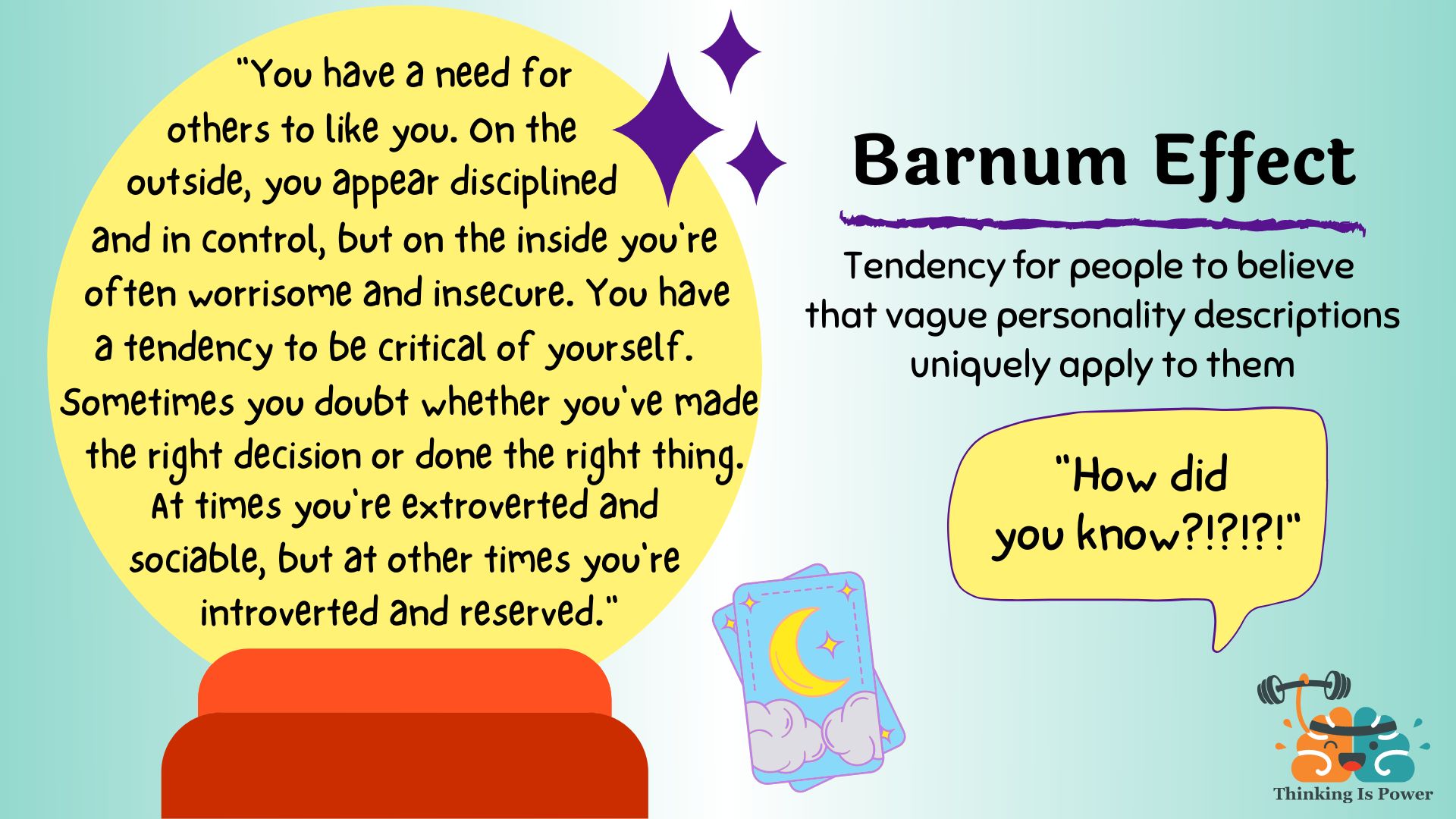

Barnum Effect (aka Forer Effect)

Definition and explanation: The Barnum effect describes the tendency for people to believe that vague personality descriptions apply uniquely to them, even though they apply to nearly everyone. If you’ve ever read your horoscope, visited a psychic, or even taken a personality test and thought, “Wow, that was so accurate! How did they know?!?”, you’ve likely fallen for the Barnum effect.

The Barnum effect is named after the famous showman P.T. Barnum, but it was first described by psychologist Bertram Forer in 1948 (hence its other name). In an experiment on psychology’s favorite “lab rat” (i.e. undergraduates), Forer gave his students personality tests and told them he would analyze and provide each with individualized feedback. Overall, the class rated their results as very accurate (an average of 4.3 out of 5).

The kicker, of course, was that all students received the exact same results, which included statements such as:

- You have a great need for people to like and admire you.

- You have a tendency to be critical of yourself.

- Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside.

- At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing.

It’s not hard to understand why the students thought these statements applied to them…they apply to nearly everyone. But the students interpreted the generic statements as applying specifically to them. Thus, they fell for the Barnum effect.

To understand why, let’s take a closer at the statements that produce the Barnum effect. Barnum statements are general and applicable to nearly everyone. But their vagueness is their “strength,” as individuals each interpret them with their own meaning. They’re also mostly positive, as we prefer being flattered to hearing negative things about ourselves. And they often include qualifiers, like “at times”, or simultaneously attribute opposing characteristics, so that they’re almost never wrong.

Forer rightly attributed the results of his experiment to his students’ gullibility. But the truth is, we’re all gullible to some degree, which is why the Barnum effect is frequently exploited by those seeking to convince us they have deep insight into our personal psychology.

How to avoid falling for the Barnum effect: Your best line of defense against the Barnum effect is awareness and skepticism.

- Be on guard for situations where vague information might be giving the impression that results are specifically tailored to you, such as fortune tellers, horoscopes, psychics, personality tests (e.g. MBTI), online quizzes, and even Netflix watchlists.

- Remember to insist on sufficient evidence to accept any claim. Ask yourself: Could this “personalized” feedback apply to others? Am I falling for flattery? And importantly, do I want to believe? Skepticism is the best way to protect yourself against being fooled…but no one can fool us like we can.

Final note: While many people associate P.T. Barnum with the saying “there’s a sucker born every minute,” there’s actually no good evidence he said those words. For a phrase that describes our tendency to be gullible, isn’t it ironic?

[Learn more: Learn to be a psychic with these 7 tricks]

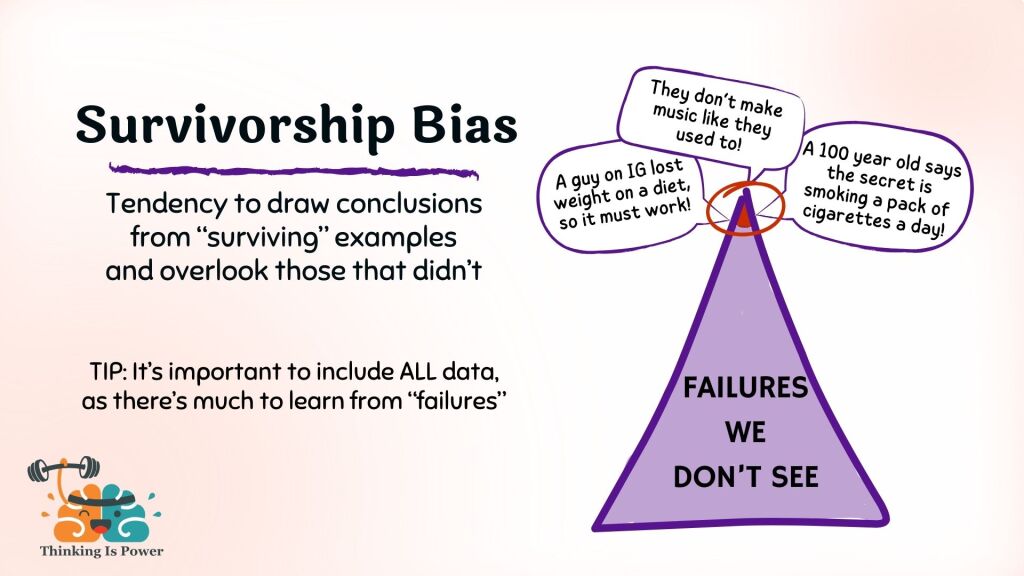

SURVIVORSHIP BIAS

Written by Jon Guy

Definition and explanation: The survivorship bias is a cognitive error that occurs when we focus on the existing elements of something (i.e., the ones that “survived”), while ignoring those that didn’t endure. This bias arises when we form conclusions based solely on successes without also considering failures.

Whether we’re aware of it or not, the survivorship bias pops up in our everyday lives. A news headline champions the success of some celebrity-endorsed diet while failing to mention the numerous people who failed to achieve the same results. Or a television program suggests that the “surviving” Egyptian pyramids couldn’t have been built with such craftsmanship and precision, without mentioning the many failed attempts that have since crumbled.

But we can be fooled by only considering “winners.” For example, we often hear about the inspiring successes of maverick entrepreneurs such as Mark Zuckerberg or Bill Gates, but by overlooking those who failed we could end up with a distorted understanding of the challenges they faced on their journeys.

Many of us witnessed survivorship bias throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. Some-expressing anti-vaccination sentiments-claimed “no one regrets not taking the vaccine.” Many examples of people who suffered or caused others to suffer as a result of not being vaccinated refute this claim. However, even if it were true, those who died as a result of not being vaccinated cannot object to the claim. As another example, some argue that SARS-CoV-2 isn’t that dangerous because they (and those they know) survived without serious complications, neglecting those who weren’t so fortunate.

Survivorship bias can also influence our personal growth and decision-making. For instance, when we seek advice from successful individuals, we might overlook the experiences of those who faced serious setbacks and failures. If we only consider the opinions of those who’ve succeeded, we might develop unrealistic expectations and face discouragement when we encounter obstacles on our own paths to success. A more balanced perspective—one that includes examples of both successes and failures—equips us to navigate obstacles and pursue success with resilience and flexibility.

How to overcome the survivorship bias: While we’re all prone to falling for the survivorship bias, there are several strategies we can use to mitigate it. First, be aware that we are all prone to this thinking error. Second, don’t be fooled by only looking at the winners, and remember that failure is often forgotten. Making informed decisions requires us to consider all data, as the challenges, mistakes, and failures of those who didn’t survive have much to teach us.

We can also keep in mind that randomness and luck often play a role in success and failure, and sometimes it really is just a matter of chance. And we can make a concerted effort to seek out those invisible data that are lurking beyond our awareness.

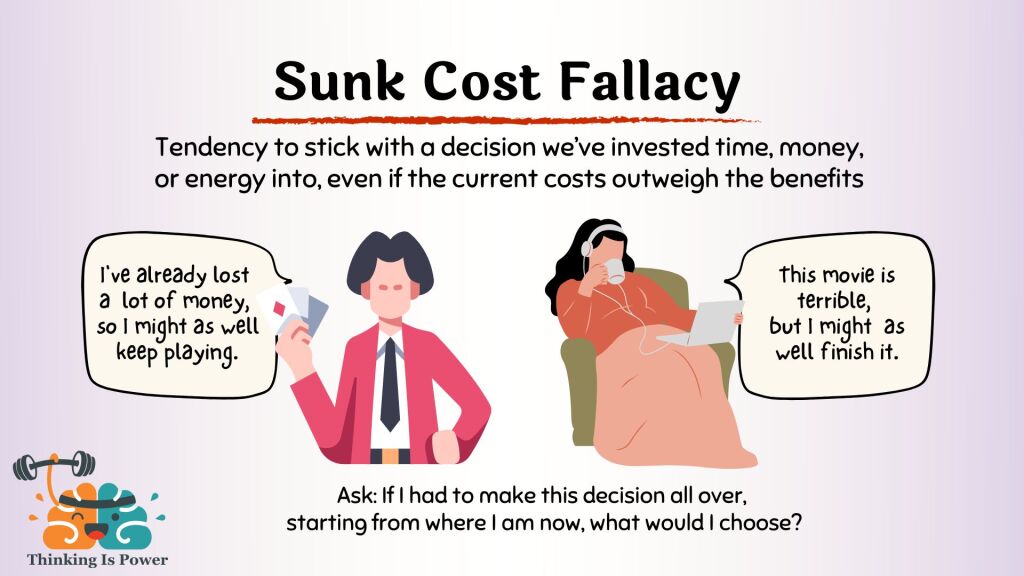

Sunk cost fallacy

Written by Jon Guy

Other names: Escalation of commitment heuristic

Definition and explanation: The sunk cost fallacy describes our tendency to stick with a decision we’ve invested resources into, regardless of the increasing negative consequences of that decision. If you’ve ever wondered why you continue watching a boring movie, or why you proceed through a terribly uninteresting book, it might be because of the sunk cost fallacy. The better we understand the sunk cost fallacy, the more likely we are to catch ourselves committing it and thus the better positioned we are to prevent ourselves from continuing on with a losing course of action.

For many of us, once we’ve invested into something, it can be really difficult to cut our losses, and instead, we end up “throwing good money after bad.” For instance, if you’ve ever tried to bluff your way through a hand of poker, you know just how hard it can be to fold once you’re “pot committed.” However, instead of folding, you up the ante, hoping that an even bigger bluff will prevent an impending loss. But in life, the stakes are much higher than they are in poker.

If the consequences of our actions have a negative impact, the rational thing to do is stop engaging in that action. The problem is, when we’ve spent time, money, or effort pursuing a decision, rather than rationally looking at the negative consequences of continuing to pursue that decision, we tend to look at it from the perspective of “losing” that time, money, or effort. Of course, that time, money, or effort is already gone (they are, after all, sunk costs), and continuing with our commitment is unlikely to bring any of it back. Typically, we commit the sunk cost fallacy because we don’t want to “lose” our investment, even if we wind up more damaged than if we had simply cut our losses. Put another way, it makes no rational sense to continue losing simply because you’ve already lost, especially since you can’t protect an investment you can’t get back anyway.

The sunk cost fallacy can dramatically affect us as individuals, and can hugely impact the course of our lives. For example, we might stay in a relationship that isn’t good for us, or one we no longer want to be in, because of how much we’ve invested into the relationship. We might remain at a job we can’t stand, simply because of how much work we’ve done for the company. We might continue spending money fixing a run-down car, when it would clearly be cheaper to buy a new one. Or we might remain in the same social circle because of how much history we have with the people in it, even though we no longer share the same interests or values.

Additionally, the sunk cost fallacy has a number of systemic effects. Oftentimes, government projects that don’t meet expectations continue receiving funding simply because so much has already been invested into them. Both Lyndon B. Johnson and George W. Bush continued sending soldiers into losing wars, and spent billions of dollars on what they both knew were hopeless causes. Thus, when it comes to fallacious thinking, sometimes lives are literally at stake.

Another pressing danger of the sunk cost fallacy is that it leads to the snowball effect, wherein we try to protect our investments by investing even more. The more we invest into something, the more we feel like we need to commit to it, which means we’ll likely expend more resources pursuing the endeavor.

How to overcome the sunk cost fallacy: Sometimes, when we find ourselves in a hole, the best thing we can do is stop digging. However, in order to do so, we must first recognize that we’re in a hole. Therefore, awareness is our first line of defense against the sunk cost fallacy. If you find yourself focused on prior losses rather than current or future costs, you can use this awareness as a signal to don your skeptical spectacles and think critically about your situation.

In addition, we should also carefully consider whether the investment we’re trying to protect is actually recoverable, or if it truly is just a sunken cost. Therefore, it’s good practice to ask yourself, “If there’s no way to get back what I’ve already put into something, am I better off investing further, or is cutting my losses the better option?”

Lastly, we should try to recognize the difference between making a decision that’s based on our emotions, and making a decision that’s based on reason. Emotions are both powerful and important drivers of our decision-making, and, like it or not, we are emotionally tied to the investments we make. Therefore, since decisions that are based on emotions are not always in our best interest, thinking critically about our investments becomes especially important.

Pingback: Postanite vidoviti uz sedam trikova - FakeNews Tragač

Pingback: Tipps zur Faktenüberprüfung: 6 wichtige Fragen, um herauszufinden, ob deine Überzeugung stimmt

Pingback: The Pros And Cons Of Heuristics: How Mental Shortcuts Can Help Or Harm Your Decision-Making – thesharpener.net

Pingback: Inappropriate Indicators And How They Can Hurt You - AlltopCash.com

Pingback: 6 WICHTIGE FRAGEN ZUR FAKTENÜBERPRÜFUNG DEINER ÜBERZEUGUNG

Pingback: 6 Key Questions to Find Out if Your Belief is True

Pingback: Sechs wichtige Fragen zur Faktenüberprüfung deiner Überzeugung

Very informative. I did not realize that someone was following me so closely! I saw myself in so many of these example and I have been practicing my critical thinking skills most of my life. Thanks

Wow great article just one correction in the confirmation bias section U talk about algorithms when u should really be using the word heuristics. This is a societal wide misconception algorithms r finite algebraic structures that r mathematically rigorous and prioritise for correctness over speed and therefore r guaranteed to give a correct answer to a very specific question. So it should read “with the help of heuristics that learn our preferences “ it is kind of ironic because by calling heuristics algorithms it is a blanket form of confirmation bias ie thinking that our biases r actually correct

Pingback: 10种影响我们决策的认知偏见 – 神农尝百草