The modern world was built by science. From medicine to agriculture to transportation to communication… Science’s importance is undeniable.

And yet, people deny science.

Not just any science, of course. (Gravity and cell theory are okay, so far.) We’re more motivated to deny conclusions that are perceived to conflict with our identity or ideology, or those in which we don’t like the solutions (i.e., solution aversion). For example, a few of the biggest denial movements today center around vaccines, GMOs (genetically modified organisms), evolution, and climate change, all of which intersect with religious beliefs, political ideology, personal freedoms, and government regulation.

But our beliefs are important to us: they become part of who we are and bind us to others in our social groups. So when we’re faced with evidence that threatens these beliefs, we engage in motivated reasoning and confirmation bias to search for evidence that supports the conclusion we want to believe and discount evidence that doesn’t.

Science denial pretends to be scientific

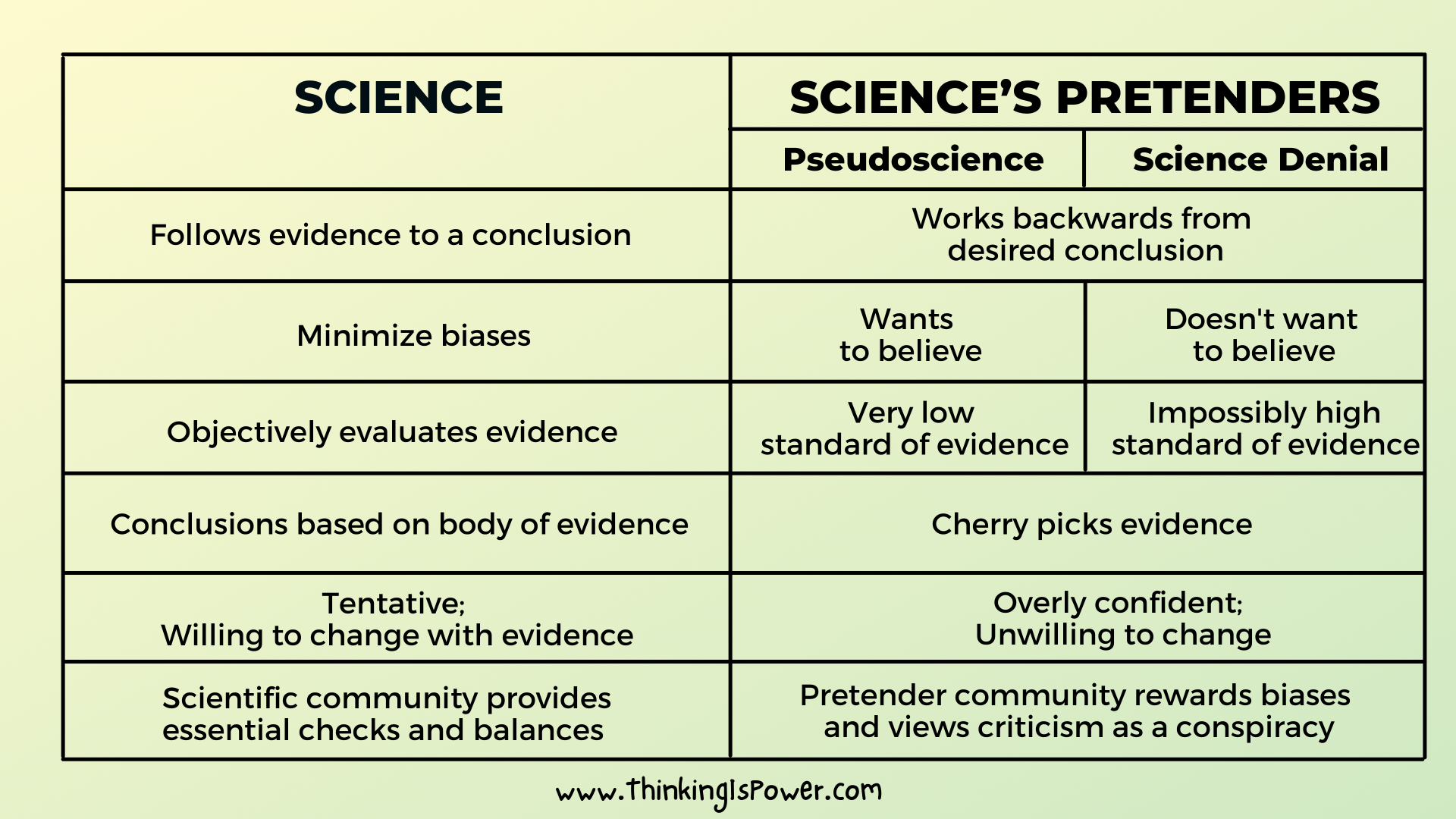

Whereas science is an objective search to understand and explain the natural world, science’s pretenders – pseudoscience and science denial – are motivated by their desire to protect cherished beliefs. Pseudoscience and science denial are two sides of the same coin, with pseudoscience motivated by wanting to believe and having a very low standard of evidence, and denial motivated by not wanting to believe and having an impossibly high standard of evidence.

Science denial is the refusal to accept well-established science. Essentially, denial suggests that the expert consensus is wrong by focusing on minor uncertainties and engaging in conspiracy theories to undermine robust science.

No one likes to think of themselves as denying science, so we fool ourselves into thinking we’re being scientific. By disguising our desired beliefs in the trappings of science, we’re able to convince ourselves that our conclusions are justified.

We convince ourselves that we’re the real critical thinkers who are “questioning the science.” We may even call ourselves skeptics. But refusing to accept well-supported scientific conclusions isn’t critical thinking, skepticism, or science. It’s denial.

Some might be offended when the term “science denial” becomes personal. And that’s understandable. But take a step back and consider how much easier it is to spot denial in others. (Flat earth is a prime example.) Then recognize that none of us are immune to denying science that conflicts with our beliefs.

The point is, science denial is real, and to have any chance at addressing the problem it’s important to call a spade a spade.

Coordinated denial campaigns and their victims

It’s important to distinguish between the purveyors of science denial and those who are fooled by it.

In particular, certain vested industries have a documented history of confusing the public about established science to protect their business models by avoiding regulation.

Their problem is that they don’ have the evidence to support their position or disprove the consensus. (If they did, they would certainly provide it.) So instead, they sow doubt. They point out minor uncertainties to claim the “science isn’t settled”, and cherry pick contrarians or fake experts to convince us that there’s no consensus.

For example, the tobacco industry manufactured doubt about the link between smoking and health problems. Fossil fuel companies used the same strategy, with many of the same think tanks and scientists, to convince the public that the science of human-caused climate change wasn’t “settled.”

Importantly, science denial is motivated by not wanting to accept a strongly-supported scientific conclusion because it’s perceived to conflict with our core beliefs… especially those tied to our identities. Special interest groups lean into the biases and emotions that make us easy targets, and convince us that it’s the scientific community (not them) who’s out to control us. Their game plan only works if we lose trust in reliable sources of information.

Both of these disinformation campaigns have done incredible harm to human and environmental health.

The point is, the goal of science denial isn’t necessarily to convince the masses that science is wrong, but to sow enough doubt that the public either gets confused or descends into nihilism.

“Doubt is our product, since it is the best means of competing with the body of fact that exists in the minds of the general public.”

Tobacco industry memo 1969

The techniques of science denial (FLICC)

Nearly all forms of denial follow the same playbook, summarized by the acronym FLICC: Fake experts, Logical fallacies, Impossible expectations, Cherry picking, and Conspiracy theories. Learn the techniques, and don’t be fooled!

FAKE EXPERTS: Uses non-experts or rare dissenters to confuse the public about an expert consensus.

Most of us trust scientists and recognize the value of expertise. And we’re especially likely to accept a conclusion if we know that experts overwhelmingly agree. So for denial campaigns to be effective, they need to convince the public that there is no consensus.

For example, in a 2002 memo to President George W Bush, Republican strategist Frank Luntz articulated the strategy clearly:

“Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate.”

In response, scientists conducted a variety of studies to determine if there was a consensus on human-caused climate change. To date, at least nine studies have found the scientific consensus to be between 91-100%. How did the denial industry respond? By disingenuously moving the goalposts from “there is no consensus” to “science doesn’t work by consensus”, which is simply not true.

The fake expert strategy can take a few different forms, such as:

- Bulk fake experts: A large number of “experts” are used to cast doubt on the consensus.

A common and effective technique to cast doubt on a consensus is to make it appear that a lot of experts disagree. It can be tricky to spot, as to a casual observer it can seem that there’s still a scientific debate where there isn’t one.

For example, the Discovery Institute, a think tank that promotes intelligent design, has (as of 2019) 1,043 signatories to their “A Scientific Dissent from Darwinism”, which states:

“We are skeptical of claims for the ability of random mutation and natural selection to account for the complexity of life. Careful examination of the evidence for Darwinian theory should be encouraged.”

Over a thousand sure seems like a lot, but the signatories’ “areas of expertise” include computer scientists, meteorologists, and engineers. What percent of biologists in the United States signed the list? About 0.01%. For reference, 98% of scientists connected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science accept human evolution.

The National Center for Science Education responded to the Discovery Institute with “Project Steve”, a list of scientists named Steve (or variations thereof, such as Stefan or Stephanie) who “support evolution.” Despite the fact that only 1% of scientists have names like “Steve”, as of 2023 the list has 1,491 signatories. Like all good parodies, “Project Steve” makes a good point – the scientific consensus for evolution is overwhelming.

- Magnified minority: A small number of contrarians are used to cast doubt on the consensus.

For example, Peter Duesberg is a molecular biologist at the University of California at Berkeley. Early in his career, he won several accolades for his research into the genetic contributors of cancer. And yet today he’s most known for being an AIDS denier. He claims that AIDS isn’t caused by HIV, but by drug use. Unfortunately, Thabo Mbeki, the president of South Africa from 1999-2008, took Dr Duesberg’s claims seriously, resulting in over 35,000 children being born with HIV and over 330,000 deaths from AIDS. To clarify, the scientific consensus is that HIV causes AIDS.

The point is, there will always be people with advanced degrees, and even experts, with crackpot ideas.

- Fake debate: Non-experts are given equal time as experts, giving the impression of debate.

A common version of this tactic is to create a false balance, in which an unsupported position is given equal time with the scientific consensus. A reputable news site wouldn’t give equal time to a geologist and a flat earther, yet in an attempt to appear unbiased will present climate change or the safety of vaccines on equal footing with those who deny reality.

Journalists are supposed to educate the public about important issues, which means accurately representing science. False balance media coverage creates confusion and reduces the public’s awareness of a scientific consensus.

LOGICAL FALLACIES: Fallacies are flaws in arguments that can lead to false conclusions. While there are about a gazillion of them, there are a few that are commonly used to deny science.

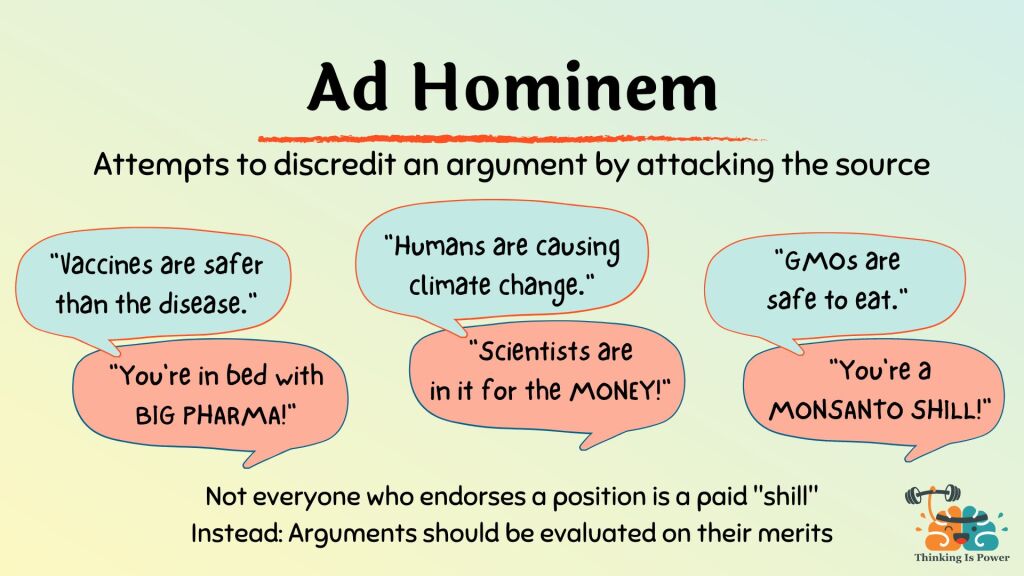

- Ad hominem: Latin for “to the person”, the ad hominem fallacy is a personal attack. Essentially, instead of addressing the substance of an argument, someone is attempting to discredit the argument by attacking the source.

One of the most common anti-science arguments is to accuse scientists of being greedy “shills” who are paid by the government or industry for their conclusions. This technique can be a very effective way to undermine trust in reliable sources of science.

Ad hominems are often a sign that someone lacks a good argument. Can’t disprove the science? Accuse the scientists of living large off grant money. (To the scientists out there paying off student loans and driving Hondas… I see you.)

The unfortunate irony is that scientists could make significantly more in industry, especially if they could publish evidence in line with industry’s goals.

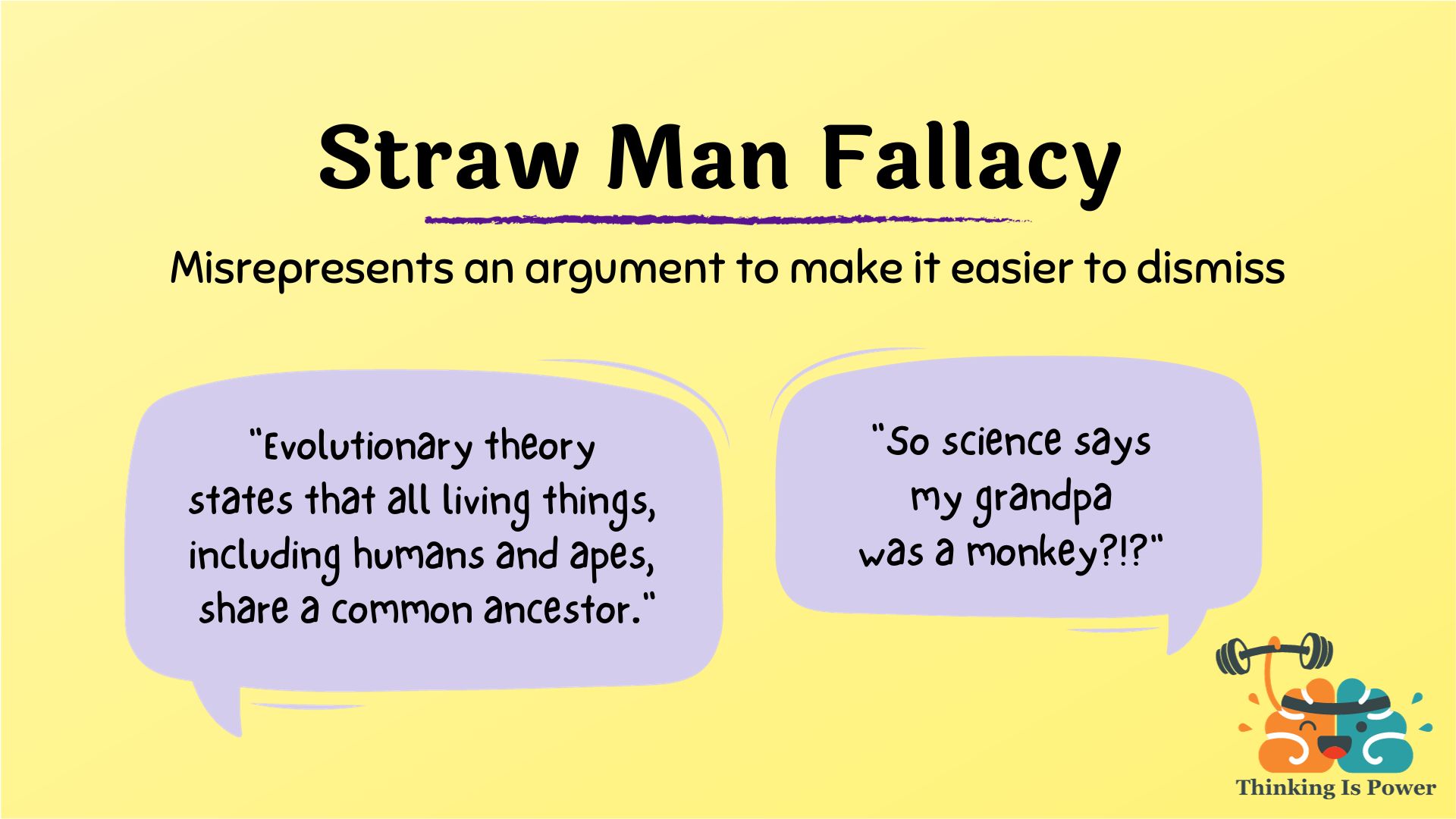

- Straw man: The straw man fallacy misrepresents an argument to make it easier to dismiss. While it can take many forms, it usually involves distorting, exaggerating, oversimplifying, or taking parts out of context.

Well-supported scientific conclusions are difficult to counter. It’s much easier to appear to “defeat” a scientific conclusion if you misrepresent it.

Examples of straw man arguments against science include things like, “Evolution says fish can turn into monkeys,” and “Environmentalists want us to live like cave people.” If these sound ridiculous, it’s because they are. (Although they are real examples!) Unfortunately, making caricatures out of scientific conclusions can be cheap and easy ways to “defeat” them.

- Galileo gambit: The Galileo gambit claims that someone must be right because they disagree with the consensus. This fallacy is a type of false equivalence, which compares things that have important differences.

Galileo Galilei was a 17th century astronomer who was prosecuted by the church for his support of heliocentrism, which states that the sun (and not the earth) is the center of the universe. Science deniers are quite fond of pointing out that “Galileo was branded a denier” for going against the consensus.

But… denying a consensus doesn’t make you right. Galileo had evidence! Most people (including scientists!) who refuse to accept well-established science are just wrong. And it was the church, not scientists, who were persecuting Galileo, as they were ideologically opposed to the Earth not being the center of the universe. Ironically, those who deny science have more in common with the church, as they’re ideologically opposed to changing their minds and not accepting evidence.

- Slippery slope: The slippery slope fallacy suggests that an action will lead to a chain of events, resulting in undesirable and often extreme consequences.

The slippery slope fallacy is often used to argue against an issue by diverting attention towards negative and unlikely outcomes, often with a healthy dose of anger or fear.

Recall that denial is often motivated by solution aversion; meaning, if we don’t like the perceived solutions to a problem, denial of the problem offers us an out.

For example, someone who is opposed to vaccines may say, “Mandatory vaccinations will lead to total control over our bodies. What’s next? Microchipping and tracking?” Or someone who denies climate change may claim, “Letting the government regulate fossil fuels will lead to communism.”

Be wary of the slippery slope. It’s important to remember that moderate positions don’t necessarily lead to extreme outcomes.

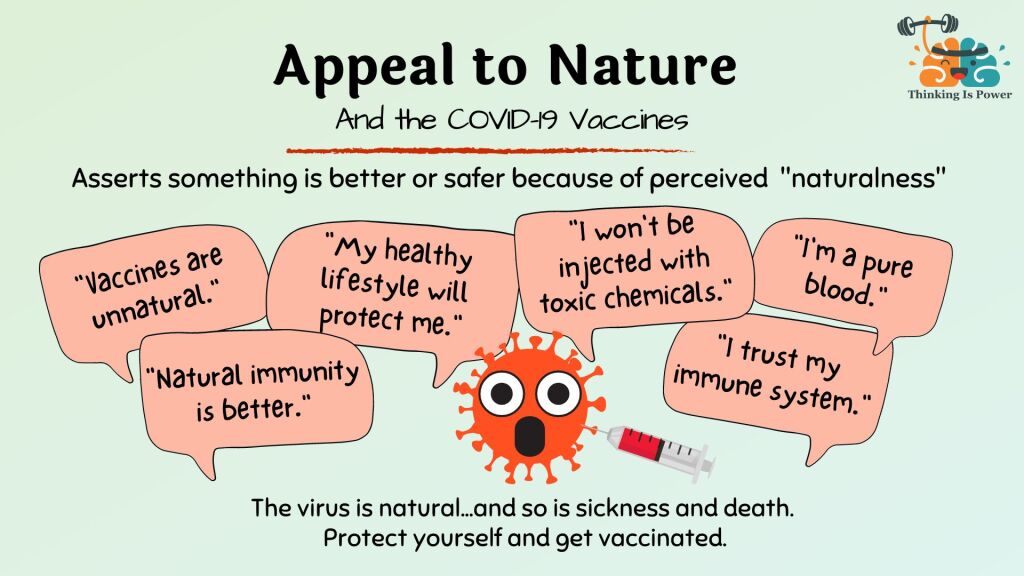

- Appeal to nature: The appeal to nature fallacy argues that something that’s perceived to be natural is better or safer than something that’s unnatural.

Appeals to nature are extremely common, as advertisers are acutely aware of our tendency to assume natural means pure, simple, and safe. But not only is “natural” difficult to define, we can’t determine if something is more effective or safer based on whether it’s from a “natural” source.

This fallacy is prevalent in alternative medicine, health/wellness, and food/diets.

For example, while the overwhelming scientific consensus is that GMO foods are safe to eat, many are afraid to consume them because they are “unnatural.” Yet there are very few things that are “natural” about even organic food (which by law doesn’t contain GMOs). For example, organic doesn’t mean pesticide-free, but synthetic pesticide-free… and some naturally-derived pesticides are extremely toxic. (Also, there’s no broccoli in nature.)

And while vaccines are among the greatest advances in the history of public health, those who are opposed to vaccines often claim they are “unnatural.” Conversely, smallpox is natural, and it killed more than 300 million people in the 20th century alone before the vaccine became available.

IMPOSSIBLE EXPECTATIONS: Demanding unrealistic standards of proof to justify not accepting a scientific conclusion.

One of the key characteristics of science is that scientific knowledge is always tentative to some degree. Theories, laws, consensuses, and even facts can all change with new evidence, although strongly supported conclusions are very unlikely to be completely overturned. There’s always more to learn, so scientists have the humility to admit there’s a chance – however small – that they might be wrong.

Purveyors of denial know that most people think science “proves” with “100% certainty”, so they exploit this misconception. They tell the public that “it’s only a theory,” even though a scientific theory is the pinnacle of certainty in science. Or they say “science hasn’t proven” something, neglecting the fact that science never proves.

Impossible expectations are central to the denial strategy, as the goal is to convince people that science “is uncertain” or “isn’t settled”, and therefore it’s premature to act. Technically, they’re right: science is never 100% certain or completely settled. But with this logic, we should never accept any scientific conclusion!

Science denial often involves moving the goalposts when the evidence is too overwhelming, a strategy that could go on ad infinitum as there’s always more to learn.

For example, those who deny evolution often point to gaps in the fossil record. Scientists know we’ll never have all of the evidence! In fact, the “joke” amongst scientists is that every gap we fill with a fossil find creates two new gaps. (Futurama has a funny clip that illustrates this point well.)

The point is, making excuses to protect cherished beliefs is a hallmark of science denial.

Those who deny science often call themselves the true “skeptics” who are embracing science’s rigor. They claim they want evidence, but they’ve set an impossibly high standard that can never be achieved. Failure to accept well-supported conclusions in the light of overwhelming evidence isn’t skepticism. It’s denial.

CHERRY PICKING: Cherry picking occurs when evidence is selectively chosen to support a desired conclusion.

Imagine a cherry tree, where each of the cherries represents a piece of evidence for a claim. If the goal is to determine the truth of the claim, it’s essential to look at the body of evidence. It’s possible to carefully select individual pieces of evidence, especially anecdotes, to support nearly any conclusion.

For example, if I wanted to deny water’s importance for living things, I could point out that water causes drownings… all serial killers have admitted to drinking water… some of the most toxic pesticides contain water… and so on. All of these facts may be true, but don’t represent the larger picture.

On a more salient example, it’s common for those who deny global warming to point to cold days or snowstorms to somehow disprove climate change. Stephen Colbert exposed the absurdity of this argument by saying he knows there’s no global hunger because he just ate a sandwich.

The point is, if we cherry pick we can quite literally miss the forest for the trees.

CONSPIRACY THEORY: Claiming that nearly all of the world’s experts are conspiring for greed or power.

Conspiracy theories are the Get Out of Jail Free card for nearly all the world’s charlatans. It’s really the only way to explain why nearly every expert rejects their claim.

While conspiratorial thinking is alluring, it’s a trap. By definition, conspiracy theories are immune to evidence; meaning, all evidence is interpreted to be part of the conspiracy and as such evidence itself is rendered moot. For example, missing evidence was hidden, contradictory evidence was planted, and so on.

Even more, the assertion that scientists are conspiring in secret to hide the truth is loaded with flaws.

Science is extremely competitive. The incentive structure rewards those who discover something previously unknown or who disprove a longstanding conclusion, not agreeing with what others have already found. Disproving “settled” science is the best way for a scientist to win a Nobel Prize and go down in history books. We don’t remember Galileo because he disagreed, we remember him because he was right.

Also, people can’t keep secrets. And the juicier the secret and the more people that know, the more likely it is that someone will talk. The incentives for spilling the beans are infinitely higher than for keeping quiet… and the grander the conspiracy the greater the chance that it will implode. (Benjamin Franklin famously said, “Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead.”)

Denial purveyors like to paint the picture of fat cat scientists loaded with grant money. This image isn’t only laughably false, it’s projection – the real money is with industry and special interest groups. For example, if the fossil fuel industry could have disproved climate change, they certainly had the money to do so. (Yet their own scientists made predictions as early as the 1970s that are remarkably similar to today’s consensus.)

It’s telling that, despite the time, energy, and money spent trying to disprove science, the best they’ve been able to do is confuse people. If they had the evidence for their own position, surely they would’ve shown us.

And now to the elephant in the room: yes, there are real conspiracies. But the fact that some people have conspired in the past does not mean any other conspiracy theory is true. We know about real conspiracies because we have evidence. Perceived motive isn’t evidence of a conspiracy, but of motivated reasoning on the part of the person pointing the finger.

The Take-Home Message

Science denial is motivated by not wanting to accept a strongly-supported scientific conclusion because it’s perceived to conflict with our core beliefs. Special interest groups push denial not by trying to prove the science wrong, but by casting doubt on the consensus and confusing the public.

No one likes to admit they’re denying science, so we pretend we’re following the process of science. Yes, science involves questioning. But we also have to be willing to accept the answers.

Ask yourself, which is more likely – that a small group of ideologues and industry leaders have exposed a global conspiracy of scientists trying to keep the truth a secret (despite their best interests)? Or that vested interests are using the one arrow in their quiver to try to con people?

The purveyors of science denial need victims. Don’t let them fool you.

To Learn More

The Consensus Handbook: Why the Consensus on Climate Change Is Important, by John Cook, Sander van der Linden, Edward Maibach, Stephan Lewandowsky

A History of FLICC: 5 Techniques of Science Denial — John Cook explains the expanded FLICC taxonomy

Science Denial: Why It Happens and What to Do about It, by Gale Sinatra and Barbara Hofer

How to Talk to a Science Denier: Conversations with Flat Earthers, Climate Denies, and Others Who Defy Reason, by Lee McIntyre

Cranky Uncle: A Game Building Resilience against Misinformation, by John Cook. (There’s also a handy Teacher’s Guide for suggestions on how to use the game in the classroom.)

Behind the Curve, a fascinating documentary about Flat Earthers

Special thanks to John Cook and Bärbel Winkler for their feedback.

Pingback: Give Science Denial the FLICC - Eco News Digest

This is excellent. However, I think inclusion of the argument from ignorance and argument from incredulity need more prominence and explanation. One is the entire core of the creationist “intelligent design” movement: if we don’t have a complete explanation of some phenomenon it is valid to posit an answer for which there is no evidence.

Another point might be the difference between a phenomenon focused inquiry to obtain knowledge and the story telling impulse requiring a narrative. Science doesn’t pretend to offer explanations for everything or construct a complete narrative. Instead it seeks to understand what we observe and provide explanatory models of what is significant to us in order to gain knowledge, which then leads to engineering solutions.

Everyone should read this as if their Democracy depends on it!

Thank you!!!

Yes! 30 years in Public Health, communicable disease prevention. The power these deniers have now scare the “heck” out of me.