Ghost hunting with science and skepticism

The haunted laboratory

The staff lab knew the lab was haunted. The atmosphere around the place was… unsettling. Workers in the creaky old building described something watching them over their shoulders and breaking out into cold sweats. And early one recent morning a cleaner ran out of the building and gave her notice after feeling a sense of dread and seeing a grey figure out of the corner of her eye.

But engineer Vic Tandy was skeptical.

Yet late one evening, while working alone in the university lab, the grey figure came for him.

He was sitting at his desk, writing, but was growing more and more uncomfortable. He was sweating but there was a chill in the room… and he had a noticeable feeling of depression.

Tandy wasn’t alone. He could feel that someone else was in the room, watching him. The hairs on the back of his neck stood up.

Out of the corner of his eye he saw the grey apparition. It stood between him and the door, so he decided to face it directly. But when he turned his head it vanished.

Terrified, he went home.

Why do we see ghosts?

I personally love a good ghost story! Sure, some are probably lies or hoaxes, but many involve experiences that are honestly difficult to explain.

The question is: Are ghosts real?

Nearly half of Americans believe in ghosts. And many personally report feeling, seeing, or even communicating with, specters. (Myself included… more on that in a bit.)

As skeptics we should be open to all claims – including ghosts. But we should also proportion our beliefs to the evidence. Ghosts are an extraordinary claim, and extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

So, let’s explore the evidence for ghosts using science, skepticism, and critical thinking.

[Related: Learn to be a psychic with these 7 tricks!]

Our brains find patterns and assume intention.

Our brains are pattern-detecting machines. Imagine being a prehistoric human on the plains of Africa. Is that rustle in the grass the wind or a predator? If you assumed it was the wind but it was a predator… you’re dead. You were more likely to survive if you assumed it was a predator even though it was just the wind.

The point is, we are the descendents of those that assumed all patterns were real and the result of intentional actions.

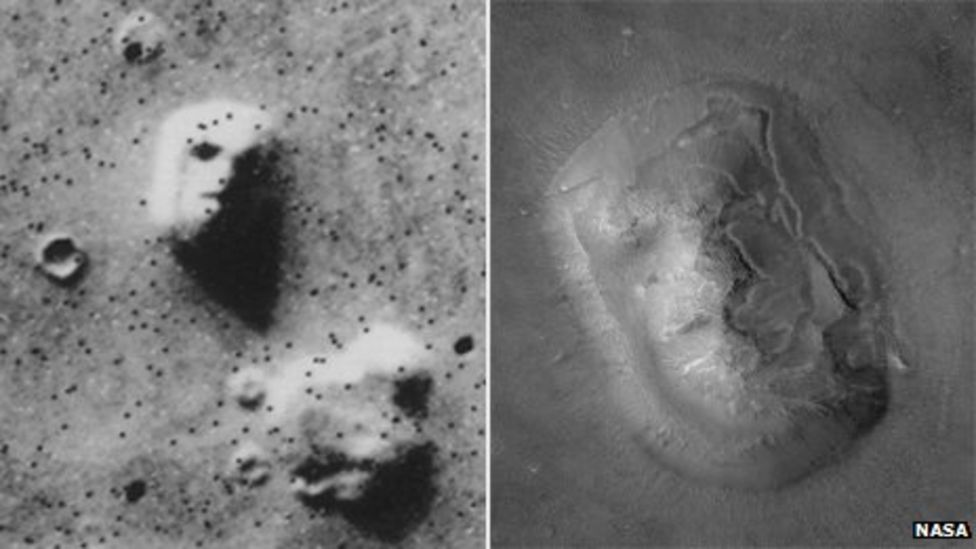

Some patterns are real, of course, and being able to identify them is important. But we’re so good at finding patterns, we perceive them everywhere. This tendency to see patterns in random stimuli, or pareidolia, is a natural function of the human brain, but it can have some interesting consequences. We see faces on grilled cheeses. We draw constellations in the stars. We connect our lucky socks to winning the game. We hear satanic messages in rock music played backwards.

Even more, we attribute these false patterns to everything from gods to angels to ghosts. And the more you believe in the paranormal, the more likely you are to think that the misty shadow you see is a ghostly body or that random noise you just heard was the sound of an otherworldly voice.

As Michael Shermer says, “We are natural-born supernaturalists.”

(Image credit: NASA; Retrieved from: BBC)

Our experiences aren’t as reliable as we think they are.

Many people assume personal experiences are the best evidence. We’ll “believe it when we see it,” we say.

The problem is, we can easily misperceive our experiences.

Our senses only take in a fraction of the information around us, and our brains then have to interpret and make sense of that information. Much of the process of perception involves our brains filling in gaps based on prior experiences, expectations, and suggestions to construct our “reality.”

Our brains loathe uncertainty, and are eager to make sense of randomness, so we tend to see false patterns more readily when our perceptions are poor. There’s a reason most ghost sightings (or even ghost hunting shows) take place at night: it’s difficult to make out detail in the dark! Or consider those times you’ve seen something move “out of the corner of your eye,” but when you turned to look it “vanished.” Our peripheral vision can detect movement but doesn’t provide as much detail.

Our expectations influence what we see.

If ghosts are the spirits of the dead, we would expect their appearance and behavior to be the same throughout history and across cultures today. However, the ghosts people “see” are strongly influenced by their cultural expectations.

Throughout the ancient world, ghosts took many forms. In Mesopotamia, if a person hadn’t properly been buried, the spirit, or Gidim, would return to haunt the living. In China, the spirit of an ancestor could appear in dreams to pass on information or warnings. And in Rome, souls fluttered about and squeaked like bats down to the underworld.

Even today, ghosts vary considerably in different cultures. Across Southeast Asia, the terrifying Pontianak is the ghost of a pregnant woman who died during childbirth… or at the hands of men. During the full moon, she takes the form of a beautiful woman with white skin and long, black hair to seek revenge. Once she lures a man, she uses her long fingernails to rip out his organs, which she eats. (Of course.) If you can drive a nail into the hole at the nape of the Pontianak’s neck, she turns back into a beautiful and submissive wife.

The Scandinavian Gjenganger is a ghost of someone who died before their time, such as by being murdered or in an accident, and has returned to exact revenge. They attack by pinching their victim in their sleep, leaving a blue mark that’s a sign of their imminent demise. To prevent someone from turning into a Gjenganger, they should be buried with specific inscriptions inside their coffin.

Hawai‘i’s Night Marchers are the ghosts of ancient warriors that roam the islands at night. They’re dressed for battle, carry lit torches, and beat drums as they march. Unfortunately, looking at them means certain death. If you’re in their path, legend has it you might survive if you strip naked, lie face down, and play dead.

The point is, we often see what we expect to see. So while we think “seeing is believing,” it’s also true that “believing is seeing.”

The terrifying ghosts that attack us in our sleep are hallucinations.

When I was very young, I once saw a ghost. I was asleep in bed next to my grandmother. I remember feeling a cold finger on my hand and fingernails scratching up and down my arm. I woke up but couldn’t move. Out of the corner of my eye I saw an old woman with long, gray hair. She was holding me down and keeping me from screaming for help. It felt like an eternity and I was absolutely terrified.

While I (thankfully) never saw that particular ghost again, to this day I’m plagued by the likely cause of my experience: sleep paralysis, a condition in which you’re awake but your body is unable to move. When we’re in deep sleep our bodies are paralyzed, likely to prevent us from acting out our dreams and potentially harming ourselves (or others). Sleep paralysis is essentially a waking nightmare.

Our minds try to explain the terrifying experience by relying on our cultural beliefs, from demons to aliens to ghosts. Or in my case, a being who bore a very strong resemblance to Disney movie witches.

(Source: Wikipedia)

Dangerous chemicals can cause ghostly experiences.

In 1912, a family moved into an old, run-down Victorian house. Shortly afterwards, they began hearing noises, such as pots and pans banging, doors slamming, footsteps, and voices. A few members of the family saw apparitions, such as a woman with a wide-brimmed hat. One of the children even complained that a “fat man” sat on his chest while he was sleeping. As the events were taking a toll on the family’s health, the family doctor made a house call and discovered the problem: the furnace was improperly installed and was pouring carbon monoxide into the home.

Carbon monoxide is a colorless, odorless gas that prevents red blood cells from delivering oxygen to the body. It can cause headaches, dizziness, weakness, nausea, confusion, visual and auditory hallucinations, chest pressure, and an unexplained feeling of dread.

Thankfully, the family left the home that day until the furnace was fixed, as carbon monoxide poisoning can also lead to death.

[Learn more about this ghost story: How skepticism can protect you from being fooled.]

Back to the haunted laboratory

Engineer Vic Tandy was frightened. But he was also skeptical.

Tandy was a competitive fencer, and the next day he brought his sword to the lab. As he prepared to polish the blade, he noticed it was vibrating, even though it was firmly clamped in the vice.

Upon investigation he found the culprit: a newly installed fan emitting low-frequency sound waves.

The human ear can generally hear sounds between 20 and 20,000 Hz. Tandy calculated the vibrations in the lab were 19 Hz, or too low to hear.

Yet just because we can’t hear the sounds doesn’t mean they don’t cause objects to vibrate. Like his sword. And his eyes.

Sound waves around 19 Hz are known as the “frequency of fear,” because they can cause general discomfort, shivering, sweating, dizziness, hyperventilation and fear, and panic attacks. And due to the vibrations in our eyes, blurred vision and optical illusions, especially in the peripheral vision.

So, they switched off the fan… and the ghosts went away.

The Take-Home Message

As skeptics we should keep an open mind about all claims, including ghosts. But we should also demand sufficient evidence before accepting any claim.

There is currently no good scientific evidence that ghosts are real. That doesn’t mean they aren’t, of course, although it’s very unlikely.

There is, however, ample evidence for why people think they see ghosts. It’s easy to understand why those in the stories above could’ve been “sure” they saw a ghost, yet anecdotes aren’t good evidence for a reason. We are easily fooled by our experiences and we often see what we expect (or want) to see. Ghosts are a very extraordinary claim, and the evidence is quite ordinary.

There will always be things we can’t explain. But just because we can’t explain something doesn’t mean it’s supernatural. Instead, we should be skeptical and assume a natural explanation.

We may never know for sure if ghosts are real. But an important part of critical thinking is learning to be comfortable with uncertainty.

So the next time you see a ghost, ask yourself: Which is more likely? Despite the lack of any good scientific evidence, you’ve seen the spirit of a dead person? Or that your brain is playing tricks on you?

To Learn More

Vic Tandy and Richard R. Lawrence, “The Ghost in the Machine,” Published in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, Vol.62, No. 851, April 1998.

Great Big Story: The ghost hunter who doesn’t believe in ghosts

Gizmodo: Some “ghosts” may be sound waves just below human hearing

PopSci: Why do we see ghosts?

The Atlantic: Global ghosts: 7 tales of specters from around the world

Loved it. Thank you.

Thank you! 🙂

Very helpful and easily understood. Thank you for this.