We live in interesting times. Humanity’s scientific knowledge has grown exponentially, allowing us to live longer, healthier lives than at any point in our history. Due to technological advances, we have access to nearly all of that information on devices we carry in our pockets.

Yet at the same time, health pseudoscience is flourishing. From homeopathy to reiki to urine therapy, potentially dangerous misinformation seemingly lurks around every corner (or every scroll through social media). Unfortunately, many of us lack the skills needed to sort the good from the bad.

Pseudoscience fools us by cloaking itself in the trappings of science. It also appeals to the part of us that needs hope when modern medicine, despite its incredible progress, doesn’t have all the answers. However, because pseudoscience doesn’t adhere to the processes that make science reliable, being misled can lead to real harm.

The first step in protecting yourself against pseudoscience is recognizing its characteristics. The best way to protect yourself against the hucksters and their snake oil, however, is to learn the techniques they use to sell it.

So let’s have a bit of fun and pretend to be grifters selling bunk.

Note: While some pseudoscience promoters are purposefully lying and trying to take advantage of people, others may actually believe in what they’re selling. Nevertheless, the techniques used to sell bunk are the same regardless of intent, and the purpose of this article is to pretend to knowingly sell pseudoscience for the sake of learning those techniques.

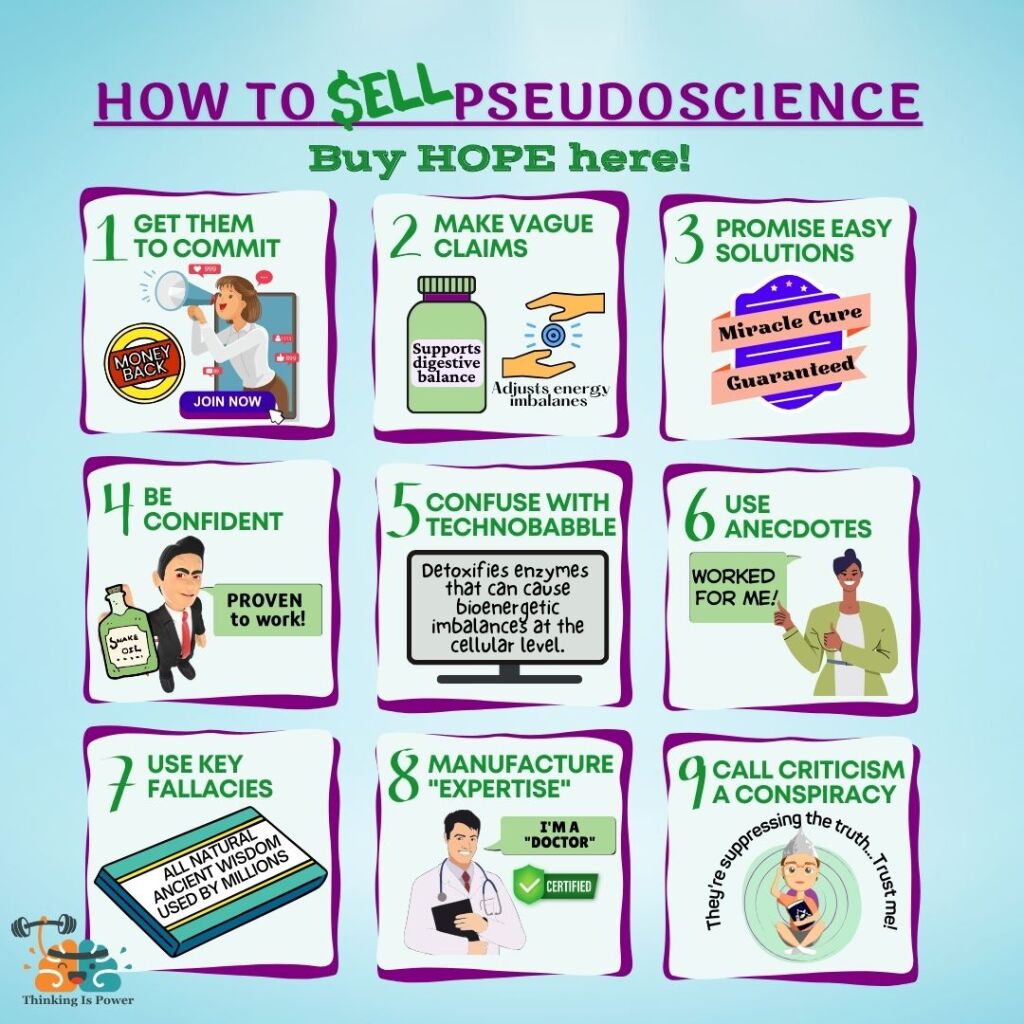

The techniques used to sell pseudoscience

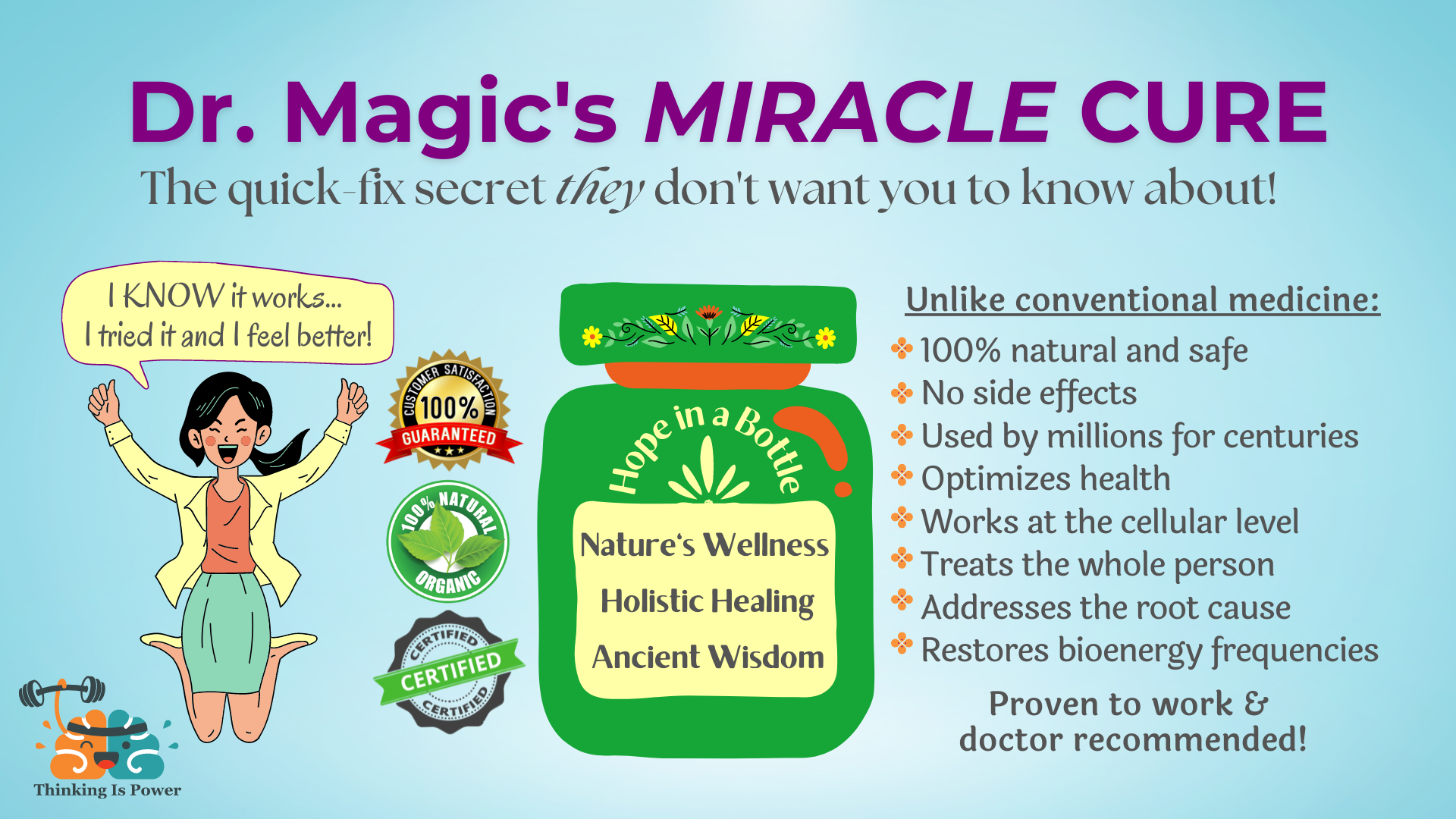

Before we learn how to sell pseudoscience, we need to know what it is that we’re selling. Yes, there’s an incredible diversity of pseudoscientific products or services. But that doesn’t matter. Because your “real” product is hope and a sense of empowerment. (Both are illusions, but that’s beside the point.)

Your goal is to convince potential customers that your product will solve their problems. Maybe they want to lose weight. Or reverse the signs of aging. Maybe they have a chronic condition that’s difficult to treat. Or worse… an incurable disease that might even be lethal. Your pseudoscience is the answer they’ve been looking for.

Now that we know what we’re selling, let’s dive into how to sell it.

1. Get them to commit

No one likes to see themselves as unintelligent, or think they’ve made an irrational decision, and they definitely don’t want to admit that they might have been conned.

So once someone has purchased your product or service, they’re likely to use confirmation bias to affirm their decision. And the more you can get them to commit the less likely they are to change their mind.

Start with a “risk free trial” or a “money back guarantee.” Create a community, such as a social media group, where customers can bond over shared values or ideology. The more you can get your customers to adopt your product or service as part of their personal brand, the less willing they’ll be to publicly admit they were wrong and therefore the more loyal they will be to your pseudoscience.

2. Make claims that can’t be proven wrong

Scientific claims are generally falsifiable, in that we can test them and potentially prove them wrong. Conversely, many pseudoscience claims are unfalsifiable. But just because you can’t prove a claim wrong doesn’t mean it’s true!

The good news for us as grifters is that many don’t understand the concept of falsifiability. Instead of trying to prove claims wrong, they look for supporting evidence…and when they find it (because we can always find evidence if we’re looking hard enough) they assume the claim is true.

The easiest ways to make unfalsifiable claims in pseudoscience are to:

- a. Be vague: Vague claims are too undefined or unclear to be tested or measured. They basically don’t say anything.

Vague claims are ubiquitous in health pseudoscience, as manufacturers aren’t legally allowed to make specific health claims unless the product has been approved by the FDA. So instead they often make broad, sweeping statements that have the added bonus of convincing customers that their product is super-spectacularly awesome!- Your product almost certainly isn’t FDA approved, so you’re going to want to avoid making specific claims, as those require evidence. Instead, master the art of bullshitting: “Keeps your digestive system in balance,” “strengthens the body’s natural defense system,” “optimizes cellular detoxification,” “reduces fatigue and maximizes energy”… and so on.

- b. Appeal to spiritual energies: The supernatural is (by definition) above and beyond what is natural, and therefore isn’t observable or testable.

Consider the pseudoscience of “energy medicine.” While energy is observable and measurable, and is used in evidence-based medicine (e.g. MRIs, x-rays, ultrasounds, etc), the “energy” in “energy medicine” is none of those things. Instead, illnesses are caused by (unobservable) “energy fields” that flow through (never identified) meridians or chakras. And of course, practitioners can “heal” you by “adjusting” these “energy imbalances.”

Some additional buzzwords associated with unfalsifiable “energy medicine” to consider include: “Vibrations/vibrational,” “Qi,” “life force,” “blockages,” “balances/imbalances,” “frequencies,” “miasms”…the list of possibilities is endless. Feel free to use your imagination!

If you’re looking for inspiration, consider using this New Age bullshit generator!

Since there’s no way to use evidence to test unfalsifiable claims, any “evidence” that appears to support them is useless. But don’t let that stop you! Make sure you say your pseudoscience is “evidence based,” even though it’s not scientifically possible.

3. Don’t worry about overpromising

Scientists have to support their claims with evidence. They’re open to all claims, but extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Luckily, as a pseudoscientist you don’t have to proportion your claims to the evidence. You’re only limited by your imagination! Exaggerated claims that promise simple solutions to complex problems are easy to sell.

For example, if you were selling a supplement you could claim it cures autism, cancer, and HIV! Or if you were peddling energy woo you could promise that it treats substance abuse and cures virtually every known illness and malady. Don’t worry that these claims sound too good to be true: remember, you’re selling hope. So go ahead and sell your “miracle cure”, with “results guaranteed!”

4. Be confident and pretend to have all the answers

Science, by its nature, is tentative and willing to change with evidence. But most people are uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity and prefer definitive proof.

As pseudoscience promoters, this one’s a no brainer. Lean in to the public’s misunderstanding of science so they trust you more than the real scientists. Point out how wishy-washy scientists sound and that they’re always changing their minds. Seriously, it’s like they don’t know anything!

So whereas a doctor may say “possible treatments may have certain benefits” but that “there’s a chance of some side effects,” you can simply assert “my product has been proven to work… with no side effects!”

5. Confuse them with meaningless technobabble

Technobabble are words that sound scientific but are either used incorrectly or they don’t make sense in their current context. Or they’re made up.

All scientific fields have technical jargon that helps experts communicate complex concepts with accuracy and nuance. The problem is, you have to be an expert to understand it. By mimicking the language of science, technobabble provides a veneer of legitimacy.

Your options for technobabble are limitless: think of it like a game of mad libs where the goal is a science word salad. For example: “Rids the body of chronic inflammation at the cellular level by detoxifying the enzymes and microbiotics that can cause bioenergetic imbalances and impair the body’s ability to self-heal.”

6. Don’t use data, use stories

If you want someone to buy your product, you could show them tables and graphs full of data obtained through carefully controlled experiments designed to minimize biases that demonstrate its safety and efficacy. Or you could just use a testimonial.

There’s a reason pseudoscience relies heavily on anecdotal evidence: they’re easy and cheap… and effective. Stories are compelling, especially those with strong emotions and vivid images.

For example, after a politician in Vietnam supposedly cured their cancer with rhino horn, demand skyrocketed and rhino populations plummeted. Since rhino horn is basically just keratin, you could get the same “medicinal” effects from chewing your fingernails. Therefore, assuming that story is true, we can safely conclude their cancer went away for other reasons. Mistaking correlation for causation is one of the major reasons we fall for bunk. Most of us don’t like to admit how easily we can be fooled.

So don’t let the unreliable nature of anecdotal evidence stop you. Consider using before and after photos, or a celebrity endorsement, or simply a quote from a customer about how it “worked for them.”

7. Make sure to include key logical fallacies

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that weaken an argument. Fortunately for us, they can be quite persuasive. While there are about a gazillion logical fallacies, there are a few that are the lifeblood of pseudoscience.

- a. Appeal to nature: Argues that something is better, more effective, or safer because it’s natural.

Not only is “natural” often difficult to define, something’s origin tells us nothing about whether it’s safe or effective. But because most people assume “natural” is better, appeals to nature are very effective, and almost a must-have on any pseudoscience product.

Buzzwords to consider using include: “All natural,” “plant based,” “chemical free,” “organic,” “nature’s wisdom,” etc. (Images of nature, such as landscapes or plants, also work.) And don’t be worried about false advertising, as with the exception of “organic” there’s no standard definition for any of these terms. They’re essentially meaningless!

- b. Appeal to tradition: Asserts that something is good or true because it’s been around for a long time.

Historical reasons aren’t evidence that something truly works; they’re just inertia. Yet because it’s commonly assumed that old means effective, appeals to tradition are a standard in pseudoscience.

Buzzwords to consider using include: “Ancient wisdom,” “ancients/ancestors,” “used for centuries/millennia,” etc.

- c. Appeal to the masses: Claims something is true because a lot of people believe it.

Popularity doesn’t determine truth: a lot of people can be wrong. But because we’re social animals, appealing to the part of us that tells us what “everybody knows” can be quite convincing.

When selling your pseudoscience, consider appealing to the many “thousands” or “millions” of customers who’ve benefited from your product or service.

- d. Straw man: Misrepresents someone’s argument to make it easier to dismiss.

Science is a process of testing ideas, of weeding out bad ones and building on good ones. It’s not perfect, but it’s the most reliable system of gaining knowledge that humans have developed. So if you want to convince customers to buy your pseudoscience, you need to convince them it’s better than what science has to offer. And to do that, you’re going to have to fudge about what science is and what it does.- So be sure to tell your potential customers that, unlike conventional doctors who just want to give you drugs, you have a “holistic” and “patient-centered” approach that’s “prevention-oriented” and “treats the root cause” of their illness. (Conventional medicine does these things, too, using evidence-based approaches, but remember your goal is to pretend otherwise.)

- e. Ad hominem: Attacks the source of the argument instead of the substance.

- Pseudoscience is likely to have its share of detractors, especially scientists who are trying to educate the public about the potential dangers of being misled by it. Your product is bunk, of course, so you can’t respond on the merits. But you’re going to want to get ahead of the criticism if you can.

One very effective technique is to call the scientists “shills” for industry or government, and claim they’re “greedy” and “in it for the money” and therefore can’t be trusted.- If you were honest you would admit that you’re the one trying to take advantage of people by selling them false hope. But you’re not being honest. You want to sell them pseudoscience. So you have no choice but to convince them that it’s the scientists who can’t be trusted…and not you.

8. Manufacture the illusion of expertise

People generally trust experts, so you have a problem: you’re not one and the real experts don’t agree with you. Thankfully, there’s an easy solution. Just pretend!

Here are a few tried-and-true techniques to help you look legit:

- a. Find or create a “doctor” or guru to be the spokesperson. The more likable and charismatic the better!

You can always find someone with an advanced degree with whacky enough ideas to be your leader. It doesn’t matter what their doctorate is in (choral conducting? English literature?)… people don’t tend to look up those kinds of details. Just remember to include “doctor recommended” on your product!

But if you can’t find someone, no worries: just make one up. Put someone in a lab coat, and give them a legitimate-sounding title, and you’re good to go. - b. Establish an organization or institution with an impressive-sounding name.

An easy way to provide an air of legitimacy to your product is to claim it’s backed by, or part of, an organization or institution. - Let’s pretend your pseudoscience product is a supplement to reverse baldness made of regurgitated cat hairballs. You might say the product is backed by the United Hair Growth Association or the Institute for Reversing Hair Loss or the Consortium for Feline-Human Hair Restoration. (And yes, I made all of that up. But it sounds better than calling it the BS that it really is.)

To really confuse potential customers, remember to box your product in an official-looking package and make sure it’s sold in drug stores!

9. Shield yourself from criticism by claiming it’s a conspiracy

Scientists are used to criticism: it’s part of the process and essential for progress. Ideas that withstand scrutiny are tentatively accepted until the evidence suggests otherwise.

So you’re going to have to explain why your pseudoscience won’t be able to pass this criticism and the experts all generally agree that your product is bunk. Your get-out-of-jail-free card is to claim that the “scientific establishment” (e.g. “Big Pharma,” “FDA,” greedy scientists, etc.) is conspiring against you to “suppress the truth.” And by claiming you’re taking on the greedy establishment to protect the public, you get to come across as the trustworthy hero.

Feel free to play with your conspiracy, just remember your goal is to shield your pseudoscience from criticism. Tell potential customers that “your doctor doesn’t want you to know” about your product, that “they are hiding the truth,” and that they “won’t hear about this in the mainstream media.” (Insert any motive here: money, control, world domination, etc.)

The Take-Home Message

Peddlers of pseudoscience know what we want: hope when medicine doesn’t have easy answers, and a sense of empowerment when our situation feels out of control.

With this in mind, it’s easier to see that, despite the overwhelming diversity of health pseudosciences, the techniques used to sell them are very similar. This is excellent news for us as consumers, as once we learn their tricks they’re easy to spot even in different contexts.

This article, while in jest, has a serious lesson: Pseudoscience can be hazardous to your health. Real empowerment comes from being able to defend ourselves against potentially harmful misinformation.

One final note: The premise of this article is based in inoculation theory, which applies the logic of vaccines to misinformation. Essentially, by exposing people to smaller bits of misinformation, and how misinformation works, we can inoculate them against it. This article uses what’s called active inoculation, as readers were encouraged to create the misinformation. In effect, instead of debunking pseudoscience, we were prebunking, or debunking in advance. Just make sure you use your “powers” for good, and not for fooling people!

Learn More: How to Inoculate Yourself Against Misinformation

Inspiration:

Pratkanis, A. 1995. How to sell a pseudoscience. Skeptical Inquirer 19(4): 19-25.

Ernst, E. 2012. How to become a charlatan.

Helpful Resource: FDA: “6 Tip-offs to Rip-Offs: Don’t Fall for Health Fraud Scams”

Special thanks to Dr. John Cook, Dr. Jonathan Stea, and Lynnie Bruce for their feedback.

Pingback: Quackery grifting — easy money for pushing pseudoscience

Pingback: Comment vendre de la pseudoscience en neuf étapes simples ? - CITIZEN4SCIENCE

Pingback: Deception, Types Of [2024] – KarenAScofield