Why We Can Trust the Scientific Recommendations on COVID-19

In 2020, medical science achieved one of the greatest accomplishments in all of human history – the development of highly effective vaccines against a deadly virus that wreaked havoc worldwide. Within the United States, where the vaccines were readily available, they had the potential to provide herd immunity in a matter of months, and thereby greatly mitigate the suffering, death, and social and economic chaos it caused. Given this, one would have thought that all eligible recipients would have rushed at the opportunity to prevent their own death, and that of their loved ones and friends, by getting a vaccination. Yet, as of the end of June, 2022, 21.7% or the U.S. population that is eligible to receive a vaccination has not done so; i.e., they have not received even one dose of a vaccine. This includes 10.4% of the adult population (≥18 years of age) [1]. This is certainly an improvement on what I reported in September, 2021 when 24% of the adults had not been vaccinated. Also positive is the fact that 76.8% of the adult population is now fully vaccinated, meaning they have received both doses of the two-dose vaccines. So, progress has been made over the last several months in protecting ourselves individually, and collectively as a society.

Nonetheless, those who remain unvaccinated, or who are delaying getting fully vaccinated, have chosen to put their own health and life, and that of others they come into contact with, at unnecessary risk. Although life has returned to normal for society as a whole, by not getting vaccinated, these unvaccinated individuals collectively delayed the “return to normal”.

They also created, and continue to create, opportunities for new variants of the virus to develop, such as the Delta and Omicron variants. Variants can develop more easily in people who are not vaccinated because the viruses within them survive in greater numbers, which thereby serves to create more opportunities for mutations to occur and new variants to develop. So, every unvaccinated person is a sort of living petri dish in which there is a greater chance for variants to emerge and spread to others. I would add that it is still possible for new and dangerous variants to develop which could set us back. Hopefully, that will not happen, but to the extent that people remain unvaccinated, there is a greater risk of this happening.

Given all of these facts, one must ask how people could choose to risk suffering and death for themselves and others when they could prevent, or at least mitigate, the harm caused by the Covid-19 virus?

There is no single answer to this, as it is largely the result of a toxic brew of scientific illiteracy, distrust of genuine experts, faulty thinking, and politics – all of which has been heated to a boil by a constant, unending flow of misinformation. Ultimately, the situation in the U.S. regarding the Covid-19 pandemic revealed a lack of understanding regarding the process of science, a lack of awareness of the criteria needed to distinguish experts from non-experts, and a lack of familiarity with common errors in thinking. All of these factors have enabled millions to be deceived by peddlers of misinformation or swayed by misguided political ideology.

The goal of the discussion which follows is to provide a greater understanding of the scientific process and related reasoning skills and, in so doing, arm readers with information to help counter the arguments of those who chose, or who are continuing to choose, to remain unvaccinated. In the event that another pandemic strikes (which is likely, though the timing is unpredictable), perhaps this information will help persuade more people to get vaccinated when this happens so that we will not repeat the incomprehensible tragedy of a million Americans dying needlessly from a preventable disease – as happened with Covid-19.

*Note: I am writing this article from the standpoint that the pandemic is over; but I am fully aware that the Covid-19 virus is still present and that people are still getting sick and dying from it. However, for most people, life has returned to normal – though there are certainly people who remain at serious risk from the virus – especially those who are not vaccinated, or not fully vaccinated.

The Scientific Process and Why It Works

It’s probably fair to say that when most people think about “science” they think about the factual information they learned in science classes. However, science is not merely the totality of facts that have been acquired; more fundamentally, science is the process by which facts are acquired. The facts that we learned in school are the “fruit” of the scientific process. Without the process, there would be no scientific facts. Understanding this distinction between facts and process is crucial because if those who are vaccine-hesitant understood the process of science they would have greater confidence in it and would be more likely to follow the recommendations of scientists regarding Covid-19 vaccinations (as well as others, such as the MMR and pertussis vaccines).

[Learn more: Science: What it is, how it works, and why it matters]

So, what makes the scientific process so special and why should we have confidence in it? The answer is that, unlike all other efforts by humans to acquire knowledge, the scientific process is based on empirical evidence and critical thinking, and because of this combination it minimizes the possibility or errors, and corrects them when they do occur.

Empiricism, Critical Thinking, Peer Review, and the Self-Correcting Nature of Science

Empiricism is the idea that verifiable knowledge is based on that which can be objectively observed and measured. Accordingly, empirical conclusions are not based on intuition, feelings, and emotions – all of which are subjective and prone to error because they cannot be observed or verified by others. Rather, they are based on objective data, and this means that the data (the facts) can be shown to be true. Just as importantly, the empirically-based scientific method is the only method that can systematically correct for the fact that we make all sorts of errors in thinking and perception that often lead us to think something is true when it isn’t. Some of these will be discussed below, but first some comments on the nature of critical thinking.

Although critical thinking may sound negative, it’s really just a term for good thinking. Essentially, critical thinking is the process of drawing reasonable, unbiased, fair, and objective conclusions on the basis of factual information. It’s the type of good thinking that we would hope a jury would do to reach a correct verdict by setting aside any biases they may have regarding the defendant, and fairly and objectively evaluating the evidence presented in court. We would also hope that they would look for errors in the arguments made by the attorneys, as well as possible errors in their own thinking, which might otherwise lead them to reach the wrong verdict.

To carry the analogy one step further, in a court of law the jury is supposed to reach a decision that is “beyond a reasonable doubt” – not necessarily one that is absolutely certain. Indeed, absolute certainty is rarely possible in the judicial system, and so jurists usually have to decide what verdict is the most reasonable. Although there are instances in which absolute certainty can be reached as, for example, when a video showing the defendant committing a crime is provided in court, the reality is that, in most cases, the jurists have to make a decision based on the weight of evidence.

This is very similar to what happens in science. In science, the data obtained through empirical research are interpreted based on critical thinking and an understanding of the state of knowledge on a topic. In some cases, definitive conclusions can be drawn based on the nature of the evidence; whereas in others, scientists must draw reasonable conclusions based on the weight of evidence available at the time – just as jurists must do. However, unlike the situation in court cases, the ability to draw reasonable, informed conclusions in a scientific field of research, and to properly assess how likely those conclusions are to be correct, requires extensive knowledge and experience regarding the specific research topic. This requires many years of specialized education and research experience. For highly technical areas, such as those involving vaccine research, the general public simply does not have the level of knowledge to “do their own research” or draw conclusions that contradict those of the scientific community. This statement is not, in any way, meant to demean the general public. Nor is it “elitist” – just as it is not elitist for the FAA to tell someone they can’t fly a plane if they aren’t a pilot. It’s simply an assertion of an obvious fact; namely, we can’t be knowledgeable of something if we’ve never studied it. And, the more complex the topic, the more education required to understand it. This is one reason why we should listen to virologists and epidemiologists who encourage us to get vaccinated and not to contrarian talk show hosts, politicians, and people on the internet who lack expertise in the development of vaccines and the assessment of their safety and efficacy. Again, just as it would be unwise to let someone fly a plane because they read some things on the internet and feel “really confident” they can fly a plane because “they’ve done their own research”, so is it unwise to listen to those who have no qualifications regarding the science of vaccines when they tell us to ignore those who do.

There is one important difference between the process of science and that which occurs in the legal system which I want to mention. In a court of law, opposing lawyers are paid to convince a jury that their position is correct – regardless of whether the lawyers actually believe the positions they are advocating. Defense attorneys, for example, may be assigned a case by their law firm and told to convince the jury that the defendant is innocent – even if the lawyers personally think the defendant is guilty. Prosecutors do the same thing. So, the lawyers for both sides pick and choose, and emphasize, only that information that will best support their case – regardless of whether they think the conclusion is correct or not. The truth is irrelevant to the lawyers (unless, of course, they can choose to represent only those clients they believe). In essence, this means that lawyers engage in rhetoric, which, in this context, means they give arguments to support the conclusion they have been paid to support. They are not doing science, they are engaging in rhetoric.

So, this aspect of the judicial system is absolutely NOT how science works. Science is a search for truth. It’s about finding out what is really happening and trying to correctly explain how it happens. Accordingly, scientists use factual knowledge, coupled with critical thinking, to draw conclusions. The conclusions are not foregone; they’re based on evidence. And, if the evidence contradicts what scientists hypothesized was true, they acknowledge that they were mistaken and conduct more research to obtain more information. The goal isn’t to win an argument, as is the case with lawyers. The goal is find out the truth.

Unfortunately, many of those who oppose scientific conclusions act like lawyers and engage in rhetoric by putting forward arguments that are not based on facts; or, at least, not on an accurate and comprehensive set of facts. In many cases, the truth isn’t actually relevant to them. Rather, for political, ideological, or monetary reasons, they simply want to win an argument that supports their position regardless of whether the evidence supports it or not.

Peer review is a crucial component of the scientific endeavor and is the process by which experts review and evaluate the results of research on a topic. This process is one of the foundations of science because it means that science is self-correcting. Mistakes can certainly be made by scientists, but the peer review process, coupled with the fact that research results are empirical and objective, make it possible to identify errors and correct them.

This is one of the great strengths of science and it is why the recommendations on mask wearing changed. Early on, evidence suggested that masks might not be very effective in preventing infections; but, as more research was done on the effectiveness of masks, the data showed that mask wearing was beneficial. To those who did not understand the scientific process, this led some to mistakenly conclude that scientists were “wishy-washy”, or that everything they were saying was just a matter of personal opinion, or, worse yet, that scientists were politically motivated in some way. But, that is not the case. The empirical data obtained through the scientific process, coupled with peer review, showed that the initial recommendations needed to be modified. The process of science worked; corrections were made based on new data – and that was a good thing! Lives were saved because of it.

In contrast to science, one of the hallmarks of non-science is that mistakes are rarely, if ever, discovered – much less corrected. This is because adherents don’t test and evaluate their ideas. In other words, they don’t conduct research, and they don’t use appropriate/comprehensive evidence and sound reasoning to evaluate information and conclusions; rather, they believe what they want to believe, regardless of the facts. And, because they lack evidence to support their positions, they often attack scientists on a personal level, accusing them of dishonesty or bias. This is what lawyers often do, i.e., they attempt to discredit a legitimate witness if, by so doing, it improves their chances of winning the case. As with lawyers, the goal of those opposed to science is to win the argument by whatever means, regardless of the truth.

The fact that science is the best means we have of gaining knowledge is right in front of us every day. The modern world of cell phones, airplanes, rockets, medicines, CAT scan machines, and even the food supply is based on science. Because it is based on the testing of ideas and peer review, the process of science works better than any other approach to understanding the world. These are some of the reasons why we should have higher confidence in scientific conclusions that those promoted by non-scientists, especially when there is a strong consensus regarding the conclusion. Additional reasons are discussed below.

Some Cognitive Errors that Are Mitigated by the Scientific Process

The human brain doesn’t process the information it receives perfectly. To further compound the problem, we all have biases which distort our understanding of the things we experience and think about. This combination leads all of us, to varying degrees, to make mistakes in how we perceive and understand (or think we understand) the world. The scientific process is built on an understanding of these sources of error and it deliberately attempts to mitigate them.

While there are many errors in reasoning that can cause us to make mistakes, a few that are particularly relevant to understanding Covid-19 are discussed below.

False Causes, Placebos, Nocebos, and Errors in Risk Perception

One very common cognitive error is the False Cause fallacy, which can also be called the mistaking correlation for causation fallacy. In other words, if one event follows another, we often assume that the first event caused the second. While this is sometimes true, sometimes it’s simply a coincidence. Unfortunately, our brains are highly vulnerable to this type of error because they are ‘hard-wired’ to look for connections between events for the simple reason that our survival depends on it. For example, if we observe that people get sick after eating a plant, we conclude that the plant is poisonous and stop eating it. So, most of the time, the tendency to perceive cause-effect connections between events is a good thing. But, when we see cause-effect connections when there are none, it can lead to mistakes. Most superstitions are based on this fallacy – such as the idea that black cats cause bad luck.

This error is particularly common when people are trying to make health-related decisions. For example, let’s say that Maria has a very bad headache and her friend convinces her to try an herbal tea that purportedly treats headaches. Sure enough, her headache goes away and Maria concludes that the tea was the reason. While this could be true, there is not enough evidence to conclude that it is. Why? Because it’s also possible that the headache would have gone away on its own. After all, headaches, and many other illnesses don’t last forever. People normally recover from them – with or without treatment. Given this, it’s entirely possible that drinking the tea did NOT cause Maria’s headache to go away – the timing may simply have been coincidental – and so her conclusion that the tea cured her is based on insufficient information and therefore represents an error in reasoning.

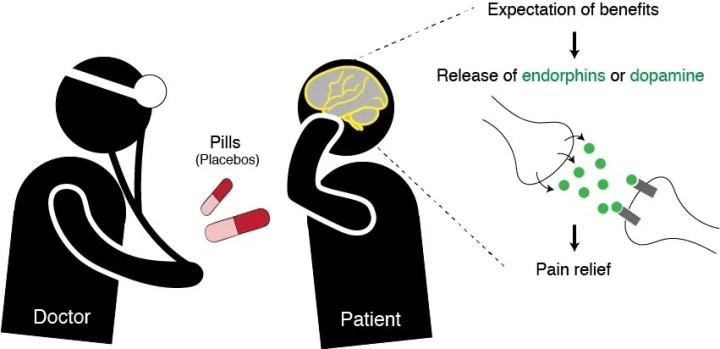

There is a related source of error that may also have been a factor in Maria’s conclusion; namely, the placebo effect. A placebo is an inert substance that doesn’t have any active ingredients that could affect a medical condition; however, when given to a person who thinks it will help, the person feels better and their symptoms improve. Therefore, Maria may have felt better simply because she thought the tea would work – not because the tea really did anything.

(Source: Harvard)

To further complicate the situation, people sometimes experience a nocebo effect – the opposite of the placebo effect. In this case, a person believes they will feel badly because of a treatment, and so they do. They can even develop psychosomatic conditions such as skin rashes, nausea, or low grade fever – even though nothing is physically wrong with them.

Scientists who study medical treatments are aware of these effects and errors in reasoning that can lead to incorrect conclusions about the effectiveness of medical treatments. So, when they conduct research to test a drug, they correct for these sources of error through the design of the research project.

When testing a new treatment, researchers randomly divide subjects into two groups, one that receives the treatment and a control group that receives a placebo. Only if the results of the treatment group are significantly better than those of the placebo group can the researchers conclude that the treatment is effective. It’s very important to understand that, if no control group is used, it is absolutely IMPOSSIBLE to conclude that a treatment worked because of the possibility of coincidence or the placebo-effect. As regards the Covid-19 vaccines, they were shown to be highly safe and effective based on a comparison with placebo groups.

To use a specific example of the False Cause fallacy related to the Covid-19 pandemic, some people claimed that hydroxychloroquine was a cure and/or preventative for Covid-19. Why? Because some people got better after they received this drug. However, when it was studied using both control groups and placebo groups, it was found to be ineffective. These patients would have recovered anyway based on their own body’s response to Covid-19 and/or the effectiveness of other treatments they were receiving. The scientific method corrected for this False Cause error and showed that hydroxychloroquine was, unfortunately, not efficacious in treating Covid-19 [2].

It’s also important to understand that all medical research focuses on both the effectiveness and safety of a treatment. In fact, the safety of any new medication is tested first. If it appears safe, the research focus then shifts to the treatment’s efficacy – though safety continues to be assessed. The use of placebo groups enables researchers to determine the safety of a treatment. All side-effects are recorded in both groups to determine if they are real; or, if they are the result of the nocebo effect. After receiving any treatment, some people will, coincidentally, get sick or die from something completely unrelated to the medical treatment. For example, a person may have a heart attack after taking a vaccine, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the vaccine caused it. Assuming so would be an example of the False Cause fallacy. Only if a pattern emerges wherein more people experience a heart attack after taking a vaccine than those in a placebo group can we conclude that the vaccine is increasing the risk of heart attacks.

(Source: WILX in Jackson Michigan)

The drug testing process takes a great deal of time and money. For example, receiving FDA approval for a new drug typically takes about 10 years and costs around $1-3 billion. Furthermore, the research is conducted by teams of scientists (not lone individuals) because the research is so complex that no single individual has sufficient expertise to do it alone.

Covid-19 vaccines were developed and tested with this same level of rigor. Because of the devastating effects of the pandemic, the vaccines went through an accelerated development and testing process by scientists working in many countries. The rapid testing was made possible – not by ‘shortcuts’ in the process – but by making an unprecedented amount of resources available and building upon decades of prior research on similar viruses [3].

The human brain also makes errors evaluating risk perception. All medicines, including vaccines, have side effects in some people. What we need to know is how common and severe the side effects are relative to the risks posed by Covid-19. In short, we have to compare the risks of the treatment to those of not getting the treatment.

As of this writing (July, 2022), almost 87.5 million Americans ((26.3%). have contracted Covid-19, which is slightly more than one quarter of the population of the U.S. population. What is almost incomprehensible is the fact that approximately 1,013,000 Americans have died from Covid-19. This equates to roughly one out of every 332 people in the U.S. Given that there were more than 87 million cases of Covid-19 in America, this means that about 1.15% of those who contracted Covid-19 died from it. [1]. To put all of this in context, in both 2020 and 2021, Covid-19 was the 3rd leading cause of death in the U.S. after heart disease and cancer, respectively. [4]

Worldwide, more than 554 million people have contracted Covid-19 and more than 6.3 million have died. So, for the world, the death rate for those who contracted Covid-19 was about 1.14% – which is almost identical to that of the U.S. [5]. However, when people consider a number like 1.1%, the risk of dying from Covid-19 may seem very small to them; “So small”, they might tell themselves, “I don’t need to be vaccinated”. But, would they get on an airplane if the chances of the plane crashing were 1.1%; i.e., if about one out of every 100 planes that took off crashed?

As we know, Covid-19 has been able to infect some people who were vaccinated, and some of these people died as a result of the infection. For those that do not understand vaccines and relative risk, this may have led them to conclude that there is no point in getting the vaccine. “After all”, they may think, “If I can get Covid-19 even if I’m vaccinated, why bother getting it? The vaccine doesn’t work anyway”. However, this is a major mistake for a few reasons. First, no vaccine is 100% effective, and no vaccine can prevent infection against all variants of a virus. (Even flu vaccines aren’t perfect.) But, just because something isn’t 100% effective doesn’t means it’s worthless. If the vaccine can prevent infections in, say, 80% of the people who receive it, that’s far, far better than no protection. Furthermore, even if a vaccine doesn’t prevent an infection in some people, the fact is that, in the vast majority of cases, the resulting sickness will be less severe than if the person had not been vaccinated. That, too, makes it worthwhile.

This is entirely consistent with the Covid-19 vaccines. For example, the Pfizer vaccine reduces the risk of severe illness by 91% in people aged 16 and older, and the Moderna vaccine is 94% effective at preventing Covid-19 with symptoms for those in the same age group [6]. Clearly, these vaccines are remarkably effective at preventing serious illness. Furthermore, the death rate for those who are unvaccinated is many times higher than for those who are vaccinated. For example, “During October-November (2021), unvaccinated persons had 13.9 and 53.2 times the risks for infection and Covid-19 associated death, respectively, compared with fully vaccinated persons who received booster doses, and 4.0 and 12.7 times the risks compared with fully vaccinated persons without booster doses.” [7] One group of scientists estimated that approximately one third of the million deaths (300,000) caused by Covid-19 could have been prevented had the people who died been vaccinated. [8]

Any deaths are tragic, but the facts just cited means that the vaccines are very effective and that the chances of dying from Covid-19, if you are vaccinated, are small. Furthermore, it is also very important to know that, out of the millions of vaccinations given, there is no evidence that anyone has died from the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines (but more than one million Americans have died from the virus). And, of the minuscule number of adverse reactions reported by just 0.05% of the recipients, the majority were headaches, fatigue, dizziness, chills, and nausea – which is typical of the side effects of other vaccines as well [9].

As regards the Johnson and Johnson vaccine, there were a very small number of cases of serious blood clotting side effects, and one death, associated with the vaccine. Because the safety and efficacy of vaccines is monitored by scientists, the government, and health providers, the use of the Johnson and Johnson vaccine was severely restricted in April of 2021 [10]. This highlights how great the concern is for the safety of vaccines by the scientific community, the government, and health care providers. In stark contrast, did any of those people who argued against vaccinations note these facts? Did they feel any remorse at all for having encouraged people to take a course of action that led to more than a million deaths in our country?

Given this, it is abundantly clear that the risk of serious side effects and death from a vaccination is extremely small and vastly outweighed by the risk of dying from Covid-19 if unvaccinated. In short, the fear of the vaccines is greatly out of proportion to any risks they may pose.

Another reasoning error we make is to ignore non-events and focus only on events that have occurred. In effect, we don’t notice what didn’t happen. Normally, that makes perfect sense, but when trying to judge the risk of dying from Covid-19, and the risk of vaccine side-effects, this type of thinking can lead to serious, life-threatening mistakes. For example, because of the effectiveness of the MMR and polio vaccines, people born after the development of these vaccines have not experienced the tragedy of thousands of childhood deaths each year from measles, mumps and rubella, or the crippling effects of polio. The deaths and debilitations that did not occur because of the vaccines are non-events that don’t register with many people in this age group; instead, what registers is the very small number of adverse events which occur (or which were alleged to have occurred based on the False Cause fallacy). Consequently, they have erroneously concluded that vaccines are dangerous and shouldn’t be administered. That this is a mistaken perception is shown by the fact that thousands of lives are saved every year by these vaccines.

Some Cognitive Errors that Interfere with the Ability to Distinguish Experts from Non-Experts

Because of a lack of ability to distinguish experts from non-experts, a lot of people are understandably confused about Covid-related messages and simply don’t know who to listen to among the many voices they are hearing. For this reason, it’s important to consider what makes someone an expert. An expert is a person with a high degree of skill or knowledge derived from education, training, or experience. As regards scientists, including those in epidemiology and virology, they would typically have three degrees: a Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorate (Ph.D.). Obtaining these degrees is a rigorous process that typically requires ten or more years of higher education to complete.

With this in mind, consider that tens of millions of people in the U.S. have decided to reject the science regarding Covid-19 vaccines in favor of the contrarian views expressed by people with no education or training in the fields of virology, epidemiology, or vaccine development. This has happened because the concept of expertise has been under assault for years. Consequently, experts are often ignored and even vilified – and are sometimes threatened with death (see below).

Aside from scientific illiteracy, several cognitive errors contribute to the inability to distinguish experts from non-experts. One of these is the mistaken belief that, just because someone – such as anti-vaxxer – is confident, they are correct. Empirical research shows that the confidence people have regarding their beliefs is not a reliable indicator of the correctness of the beliefs [11]. In other words, we can’t use a person’s level of confidence as the sole basis for trying to separate misinformation from factual information. Rather, we have to examine the evidence and logic of their claims to determine if they are correct. Returning to the court of law analogy, both the prosecutor and the defense attorneys will confidently assert the guilt or innocence of the defendant, respectively, but they can’t both be correct. Another common source of error in deciding who is an expert is to mistakenly conclude that because someone is an expert in one field, they are an expert in another. As regards the Covid-19 situation, one U.S. Senator, Rand Paul, is encouraging people not to wear masks and not to be vaccinated if they’ve already had Covid-19. This Senator has a medical degree in ophthalmology, and when people know that he is a doctor, they tend to assume that he knows as much about Covid-19 as the experts he is challenging. But, he isn’t an expert in the relevant field. Yes, ophthalmology and epidemiology are science-based, medical fields, but they are different fields. Furthermore, research shows that receiving a vaccine after having Covid-19 can substantially improve one’s immune response [12] [13].

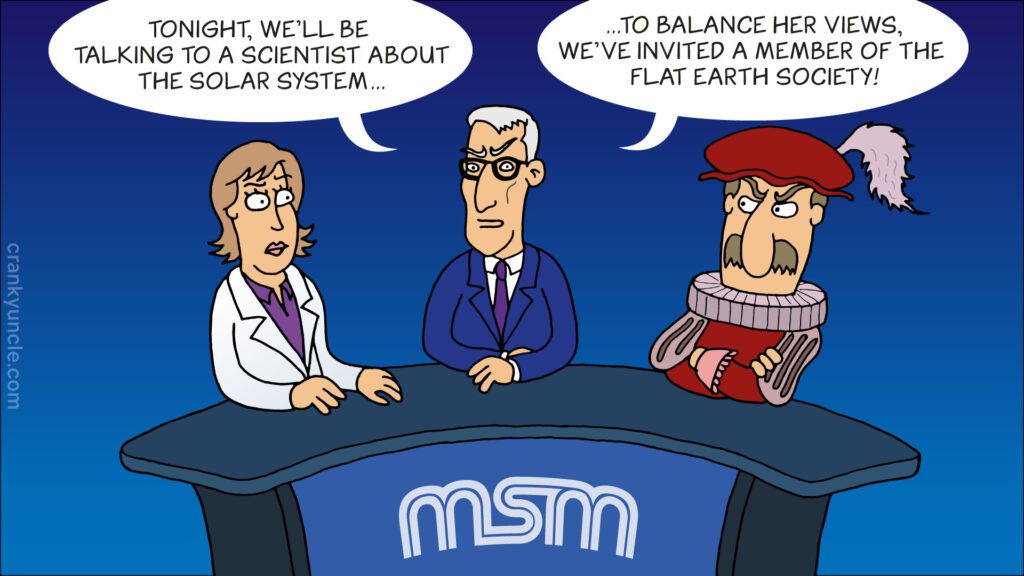

Another source of error regarding experts is related to criticisms of Dr. Fauci, who is often portrayed as a sort of lone, aberrant, scientist who is forcing his personal, politically-motivated views on the country. This is an attempt, like that used by lawyers, to discredit a legitimate authority in order to win an argument. Based on this line of thinking, his recommendations can be ignored because they are biased and idiosyncratic – and wrong.

In reality, Dr. Fauci has served as the voice of the scientific community, consisting of virologists and epidemiologists from all over the world. However, by falsely portraying him as lone scientist, his critics are using a version of what is called the False Balance tactic. This occurs when two people, such as Senator Paul and Dr. Fauci, are both represented as two legitimate experts on a topic. The public infers that, because they are seeing two experts with differing views, it’s just as likely that Rand Paul, rather than Dr. Fauci, is correct regarding Covid-19 facts and recommendations. However, in this case, the Senator isn’t an expert and his views do not represent those of the scientific community. In contrast, Dr. Fauci is an actual expert and his recommendations represent the consensus views of experts worldwide. He has decades of research and experience specifically in the field of epidemiology. There is absolutely no balance between the recommendations of Dr. Fauci and the Senator; it is a false balance. Unfortunately, this tactic had led people to reject vaccines and mask wearing, and to direct animosity and even death threats toward Dr. Fauci. He had to have personal security guards because of false claims made about him. [14]

(Source: Cranky Uncle)

Lastly, there will always be some experts who contradict an overwhelming consensus. However, the consensus view of the scientific community is much more likely to be accurate than the lone contrarian. The old adage that “many minds are better than one” is usually true. So, it’s best to go with the consensus scientific view – especially if your life and that of your loved ones are at stake.

Other Cognitive Errors that Can Result Reaching Incorrect Conclusions

Dissonance: I Don’t Want to Hear This!

The most over-arching and pernicious cognitive error is our tendency to ignore facts that contradict what we want to believe is true. This tendency results from cognitive dissonance, which is that uncomfortable feeling of psychological tension, confusion, or even anger that we experience when presented with information that contradicts what we believe and, especially, what we want to believe. When this uncomfortable mental state arises, we want to end it as quickly as possible. If we eliminate the dissonance by referencing factual information and logical arguments that contradict a claim that has been made to us, then that would constitute appropriate dissonance reduction. To use a simple example, if someone falsely claims that earth is flat, then it is appropriate to marshal the wealth of empirical facts available to us to show that this is not true and reject the claim. But, if we arbitrarily (i.e., without good reason or evidence) dismiss conflicting information because of bias or fear, and/or search only for information that appears to support our position, this is inappropriate. This form of dissonance reduction is very likely to occur if the belief that is being challenged is very important to us, and especially if it is tied to our sense of identity.

(Source: KirstenImperial)

If we care about the truth of a claim, we have to have good reasons for believing what we believe. We can’t arbitrarily decide to ignore or devalue conflicting information because we don’t want to change our minds. Returning to the court of law analogy used earlier, jurors shouldn’t arbitrarily dismiss evidence because they don’t want it to be true. If they are fair-minded and reasonable, they have to consider the preponderance of evidence, without bias, and with the goal of determining the truth.

Inappropriate dissonance reduction is highly relevant to the pandemic situation because it was the fundamental basis for opposition to vaccinations and mask wearing. The empirical data regarding the safety and efficacy of the vaccines, and the effectiveness of masks, is as clear-cut and unambiguous as it could possibly be. The pandemic is now a pandemic of the unvaccinated. Yet, those who oppose vaccines and masks dismiss this information in an attempt to eliminate their dissonance regarding their decision not to be vaccinated. Some do this by fabricating bizarre conspiracy theories about the government placing tracking devices in the vaccines, or becoming magnetized by the vaccines, or claiming that the government and hospitals (all over the world!) are making up the data about death rates. These conspiracy theories were fabricated out of thin air, with no basis in evidence or logic. This is a sure sign of inappropriate dissonance reduction.

Examples of Misinformation about Covid-19 that are Related to Dissonance Reduction

Some of those opposed to Covid-19 vaccinations claim that Covid-19 is no more dangerous than the seasonal flu, and so there is no reason to wear masks or curb social activities. However, their claims about the flu and Covid-19 being equally risky are wrong. Between 2010 and 2020, the average number of deaths each year from the flu ranged from 12,000 to 61,000. So, to date, Covid-19 has been almost 17 times as deadly as the deadliest flu season in the last several years, and almost 84 times more deadly than the least severe flu season [15]. In addition, Covid-19 is more contagious than the flu, which also makes it more dangerous [16].

Some of those who oppose vaccinations do so based on the belief that there may be unknown, long-term side effects of the vaccine that make them too risky to use. So, it is worth noting that, based on the history of vaccine research, allergic side-effects typically occur within minutes or days following the administration of a vaccine. Other Covid-19 vaccine side effects have a median onset of 1-3 days [17]. To date, hundreds of millions of vaccinations have been administered and there is no sign of any long term side-effects from these vaccines – though there are signs of long-term, persistent effects from Covid-19 infections [18] [19]. To ignore this fact, and the greater risks posed by Covid-19 than the seasonal flu, are examples of inappropriate dissonance reduction.

Misunderstanding the Definition of Freedom

Those who oppose Covid-19 vaccinations also appeal to what can only be described as a perverse sense of personal freedom and personal rights as the basis for their position. This is evidenced by the fact that they are arguing for the ‘right’ to be killed, needlessly and pointlessly, by a preventable disease; and, in the name of this type of freedom they espouse, they are implicitly arguing for the ‘freedom’ to infect and kill their fellow citizens. They are ignoring the fact that the virus is transmissible and, therefore, their decision is not just a personal choice, it’s a social choice which affects the health of others and has grave social and economic consequences.

Although it would seem too obvious to warrant discussion, it is a given that, in any society, people have to curb their personal freedom when others might be harmed by their actions, as for example, when driving a car. We follow speed limits precisely because we don’t have a right to injure or kill our fellow citizens in the name of a supposed “personal freedom” to drive as fast as we want. No right or freedom is absolute if it endangers others. This leads to the last point I would like to make; namely, the fact that we have all been required to have numerous vaccinations at some point in our lives, such as the MMR, Pertussis, Hep A, and Meningitis vaccinations. We, as a society, have been taking these vaccines for decades in order to protect our own lives and those of others. They are required of us to attend school and to serve in the military. So, if these other vaccines are okay, and if they can be required to protect our fellow citizens, it makes no sense to say that we shouldn’t take the Covid-19 vaccinations because “they take away our freedom”, or that the decision is a “personal decision”, or that efforts to vaccinate people constitute a form of “government overreach”. If it is good to take these other vaccines to protect ourselves and others (and it is), then why would taking the Covid-19 vaccine be any different? It serves the same purpose and to argue otherwise is contradictory – and dangerous. To claim that a decision not to get vaccinated is a “personal choice”, while ignoring the potentially life-threatening consequences to others, is yet another example of inappropriate dissonance reduction.

The Take-Home Message

If people had understood that the process of science is based on empiricism and critical thinking, and that it corrects for errors caused by cognitive errors and biases, much of the pain and suffering caused by Covid-19 could have been avoided. Going forward, if we can convince our friends and family to listen to experts and get the vaccinations they recommend, we will all be much better off. Thousands, if not millions, of people that would otherwise get seriously ill or die from preventable diseases will instead be able to lead healthier and longer lives.

References

1. COVID Data Tracker. (2022). Retrieved July 3, 2022.

2. Drugs.com. (2021, September 24). Retrieved September 30, 2021, from An Update: Is hydroxychloroquine effective for COVID-19?.

3. BJC Healthcare.org . (2021, January 14). Retrieved September 29, 2021, from Timeline of the COVID-19 vaccine development.

4. COVID-19 CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC. (2021). Retrieved July 3, 2022.

5. Johnson AG, Amin AB, Ali AR, et al. COVID-19 Incidence and Death Rates Among Unvaccinated and Fully Vaccinated Adults with and Without Booster Doses During Periods of Delta and Omicron Variant Emergence — 25 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4–December 25, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:132–138. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7104e2. (2021). Retrieved July 3, 2022.

6. https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus-covid-19/vaccine/comparing-vaccines. Retrieved July 3, 2022

7. COVID-19 Incidence and Death Rates Among Unvaccinated and Fully Vaccinated Adults with and Without Booster Doses During Periods of Delta and Omicron Variant Emergence — 25 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4–December 25, 2021 | MMWR (cdc.gov)

8. Americares: The COVID-19 Global Pandemic. Retrieved July 3, 2022

9. USA Facts: What the government data says about COVID-19 vaccine side effects. Retrieved July 3, 2022

10. Katella, K. (2021, August 4). Yale Medicine. Retrieved September 29, 2021, from The Johnson & Johnson Vaccine and Blood Clots: What You Need to Know.

11. Wikipedia. (2021, August 26). Retrieved September 29, 2021, from Overconfidence effect.

12. Frequently Asked Questions about COVID-19 Vaccination: (2021, September 28). Retrieved September 29, 2021.

13. Akshay Syal, M. (2021, September 13). NBC Health. Retrieved September 29, 2021, from ‘Hybrid immunity’: Why people who had Covid should still get vaccinated.

14. Doheny, K. (2021, July 29). Web MD. Retrieved September 29, 2021, from Fighting Fauci: From Ridicule to Death Threats, Attacks Continue.

15. Disease Burden of Influenza. (2020). Retrieved September 2021.

16. Similarities and Differences between Flu and Covid-19. (2021). Retrieved September 21, 2021.

17. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Approved or Authorized in the United States. (2021, September 27). Retrieved September 29, 2021.

18. Henry Ford Health: 5 Reasons We Know The COVID-19 Vaccines Don’t Have Long-Term Health Effects. Retrieved July 3, 2022;

19. Greater Than Covid: What about long-term effects of the COVID-19 vaccine? Retrieved July 3, 2022.

Special thanks to Dr. Marcus Gillespie for writing this amazing post, and for being a source of inspiration for Thinking Is Power. Dr. Gillespie and Dr. Matthew P. Rowe’s general-education science course influenced my course, this website, and me. This is a “full circle” moment, and I’m honored to share his talents on Thinking Is Power.

The real problem is this: the overwhelming majority of us cannot run our own experiments. We have to rely on the integrity and competence of the ‘experts’. And over the last few years, our confidence in the integrity and competence of these experts has been

undermined. We were very confidently assured that the Covid virus was definitely NOT an escape from the Wuhan bio-warfare lab … and then it turned out that it may have been.

Many of us who were not receptive to the anti-corporate messages of the Left, have now become aware of the financial connections between Big Pharma, and the so-called ‘experts’. The same thing has happened with mainstream journalism:once trusted, it is now trusted no longer, and with good reason.

Reason magazine has a good article on this question: https://reason.com/2022/04/03/against-scientific-gatekeeping/

It’s a shame that all of this will strengthen the religious fanatics, the mystics, the conspiracy theorists, and the charlatans.

But we cannot combat them by arguing for a quasi-religious faith in the scientific, or any other, establishment.

Hi Doug,

Apologies for the tardy response, but I sent your comment to the article’s author, Dr Marcus Gillespie, to get his response. Here is what he sent:

Hi Doug,

Thank you for reading the blog on vaccine misinformation and for your comments. You are certainly correct when you state that “none of us can run of our own experiments” regarding Covid-19 issues – or just about any other issues involving scientific research. More broadly speaking, this is essentially the same as acknowledging that no individual can replicate the development of knowledge that has been made possible by science over the last few centuries. So, as you were implying, this is why we are often reliant upon others to inform us and to guide us through the maze of information to which are exposed in our lives. This is especially true when dealing with scientific information. Given this, we are in a position of trying to decide who to listen to. This, as Dr. Trecek-King mentioned in a discussion we had on this topic, essentially comes down to trying to decide who we trust. If we trust the source, we tend to accept the claim; if not, we reject it.

With that in mind, you suggested that I was “arguing for a quasi-religious faith” in science and science experts. I realize that you were using the term somewhat metaphorically, but I would note that there is a very important distinction between faith and empirically-based trust (or confidence). This is not a case of splitting hairs, so to speak, because faith, by definition, is a belief in something in the absence of evidence to support the claim. In short, the faith-based acceptance of an idea is not predicated on evidence or logic. It is simply accepted – and that is often done even when evidence and logic contradict it. In stark contrast, the “enterprise” of science and the conclusions drawn by scientists, are based on observable evidence and logic. Accordingly, for a claim to be accepted by scientists, there must be sufficient evidence to support it and it must not contradict a well-established body of evidence, or be illogical. So, when scientific organizations established to pursue scientific research, and to make policy recommendations based on scientific research, reach a conclusion, I tend to trust it because of the way in which that conclusion was derived. In the absence of compelling, contrary evidence, I have no reason to distrust it.

So, when I argue in support of the science, I am arguing in favor of the methods of science, which are based on empiricism (observations, experiments, and studies), skepticism (i.e., “show me it’s true or reasonable to believe”), and logic. I have great confidence in the process because it is literally the only reliable method of acquiring knowledge and correcting mistakes ever devised by humans. Nothing else comes close to science as evidenced by the fact that the modern world of technology, food production, electronics, communication, medicine, transportation, and so on, is all made possible by the scientific process.

But, it is also true that the enterprise of science is a human enterprise, and so it is not perfect. Scientists, of course, can and do make mistakes. And, as noted in the article in Reason you referenced (https://reason.com/2022/04/03/against-scientific-gatekeeping/), politics can intrude into the process – especially when polices are involved that have economic and social impacts – as is clearly the case with Covid-19. So, even though the scientific approach to acquiring knowledge clearly works, it is also the case that scientists can draw incorrect conclusion from the data, especially when the research on a topic is in its early stages and data is limited. And, because of differences in risk tolerance, different conclusions can be reached regarding such things as masking, even if the underlying facts regarding the virus are understood.

Because scientific research is always on-going (it’s never complete), it’s analogous to detective work in the sense that, in the early stages of an investigation, the limited amount of data means that there are many possible explanations for what is observed. So, conclusions at this stage are highly tentative. But, as more evidence is amassed, researchers can reject explanations (hypotheses) that no longer fit the growing body of data, and gradually zero in on those that do. At some point in the process, one can have confidence in a hypothesis that, as Carl Sagan once said, is left standing after others have been eliminated.

The point is, scientific conclusions, and policy recommendation based on them, necessarily vary in terms of the degree to which we can have confidence in them; i.e., it depends on the amount of research which supports them. It also depends on the level of consensus among those qualified to evaluate the research and conclusions. So, my confidence in a scientific claim depends on the amount and quality of evidence in support of it, which is also directly related to the level of consensus of genuine experts. So, for example, if the WHO, the CDC, and similar health organizations from around the world (which are staffed with relevant medical experts) are telling me to get vaccinated, I’m going to listen to them because: 1) they are using the scientific method to study the virus; 2) their research on viruses and vaccines has been on-going for decades, 3) they are true experts the field; and 4) there is a huge, worldwide consensus regarding the efficacy of this recommendation. In contrast, I’m not going to listen to the contradictory recommendation of a lone, outlier scientist; or, worse yet, a person on a blog site or news station who has no scientific background on the topic.

In effect, when trying to decide who to listen to – who to trust – we’re dealing with probabilities. In the case of the vaccine issue, we’re dealing with the probability that the scientific community is mistaken and that those opposed to vaccines are actually correct. While it might be hypothetically possible that this is true, the probability of that is virtually zero given the state of knowledge regarding vaccines. In short, with this, or any other competing claims. I ask myself which is more likely to be correct – the global scientific community, or the dissident scientist and non-expert? Clearly, for the reasons discussed, it’s the former.

You mentioned the differing opinions of experts regarding role of the Wuhan lab, if any, in the start of the pandemic as a basis for questioning science. I would note that this is more of an actual detective story that requires an examination of records from the lab, rather than pure science per se. The science regarding the Covid-19 virus is certainly relevant to figuring out how the pandemic started, but the records from the lab are apparently the key to doing this. However, outside experts are barred from the lab and without access to those records, we may never know what actually happened. Any conclusion at this point appears to be more speculation than science – which is why various experts disagree. Using the criteria I mentioned above, there is not enough evidence (as far as I know) to draw a definitive conclusion, and there is no consensus among scientists (as far as I know). So, I am withholding judgment – and that’s okay to do this. In fact, it’s more than okay; it’s the correct perspective to take when evidence is insufficient. It’s not always possible to know the answer when evidence is lacking and so, as a member of the public, I have to learn to make distinctions regarding the level of certainty that can be provided, and to distinguish a scientific finding from an opinion.

As an important aside, I acknowledged above that scientists, being people, make mistakes – but, collectively, they make fewer of them regarding their area of expertise precisely because they are experts. Again, it’s a matter of probabilities. I would agree with the author of the article in Reason you referenced who basically said that we should never say that research on a topic shouldn’t be allowed just because of a prior consensus. Barring research is antithetical to science and would negate the possibility of correcting a mistake if there is one. It belies the fact that science is on-going. But, in the real world, we don’t pursue research on hypotheses that have already been disproven just because someone has suggested them or read about them on the Internet, nor do we pursue ideas which violate laws of nature (such as perpetual motion machines) even if people believe in them. Expertise has to guide decisions regarding what research to pursue based on what is most likely to lead to more accurate conclusions. If the consensus is challenged, the challenge should be based on solid evidence to be taken seriously. Further, the “democratization of knowledge the author references (i.e., access to knowledge – which is a good thing) doesn’t mean that everyone has the ability to draw reasonable or accurate conclusions from it. Access to knowledge doesn’t equate with the ability to make sense of it or to use it, which is why expertise matters.

I want to emphasize the fact that when I acknowledged that scientists make mistakes, I used the word “mistakes” very deliberately because there is now, in our culture, a common tendency (of millions of people) to assume that mistakes are not really mistakes, but rather, that they are knowingly false claims made by scientists as part of an ideologically-driven conspiracy. This is often done even though there is no documentable evidence of a conspiracy. When people don’t understand that science is an on-going, corrective process, and that there are, therefore, different levels of certainty regarding conclusions, they often assume that the world is awash in conspiracies whenever new scientific evidence supplants a previous conclusion, or when different people reach different conclusions.

This tendency is exceptionally dangerous because it undermines any sense that there can be confidence in any finding or conclusion. With this mindset, everything is considered to be mere opinion – much of it ideologically driven by people with sinister motives. The result is that we live in alternate realities with no common basis for dealing with issues and arriving at rational conclusions or policies. This is why science is so important because the method itself is, in principle, independent of ideology. It doesn’t matter what political party a person belongs to if the process is followed. So, what ultimately matters in science is adherence to the method, the amount of evidence to support a claim, and the level of consensus.

As regards the recommendations of the scientific community regarding Covid-19 vaccinations, the fact that the consensus is worldwide effectively eliminates the possibility that it is being driven by ideology given that the political orientations, if any, of the scientists vary from one country to another. In short, the recommendations can’t be based on a coordinated effort to deceive based on a common political ideology. And, one could also ask, “Why would the global scientific community conspire to deceive people?” And, even if such a conspiracy were possible – which it isn’t given that it would be impossible to coordinate thousands of scientists to engage in such a deception, or to keep a conspiracy of that magnitude secret, “What purpose would it serve?” The probability that there is such a conspiracy is effectively zero.

Lastly, it must be acknowledged that some experts may be motivated (for whatever reason) to deliberately distort the findings. Indeed, a researcher named Andrew Wakefield did this when he published an article implying that the MMR vaccine causes autism. That article was based on one study with only 12 subjects (i.e., it was far too small to provide sufficient evidence of a link); and, most importantly, the study was rigged – the data was falsified! Furthermore, there was never a scientific consensus that the MMR vaccine caused autism. Many studies have since been done in several countries to investigate this hypothesis. In total, they have involved more than a million subjects. These studies have absolutely, definitively shown that the MMR vaccine does not cause autism.

Because science is self-correcting, Wakefield’s article was retracted and Wakefield’s license to practice medicine was revoked because of the fraud he committed. Unfortunately, millions of people who were unaware of the concepts discussed above, and many of whom tended to think in terms of conspiracies, continued to accept the claims of a lone researcher who had lied for financial reasons, while rejecting the consensus results of scientists working independently of one another throughout the world. Tragically, Wakefield’s false claims fed a more generalized fear of vaccines, as well as related conspiracy theories about the government and Big-Pharma. Because of this, millions of people refused to be vaccinated and almost a million people in the United State have died from Covid-19. Had people listened to the consensus view of experts, this tragedy could have been greatly mitigated. In conclusion, my position on this isn’t based on “quasi-religious” faith in science, it’s about evidence and the fact that science provides the best method we have of sorting fact from fiction, and from distinguishing the probable from the improbable.

Thanks