Note: This article is the second of a two-part series on “doing your own research.” To read the first article click here.

It seems nearly everyone is “doing their own research” these days. And to some extent it’s understandable: we want to make good decisions and there’s a seemingly endless amount of information available at our fingertips.

Unfortunately, access to information simply isn’t enough. Although it’s difficult to admit, we aren’t as knowledgeable or as unbiased as we’d like to think we are. We often resort to “doing our own research” when we want (or don’t want) something to be true… and so we set out to find “evidence” to make our case. Due to an unfortunate mixture of motivated reasoning and confirmation bias, we end up wildly misled yet even more confident we’re right.

Before “doing your own research”, it’s essential to ask yourself a few key questions. What is your goal, conclusion shopping or learning? What underlying biases and emotions might influence your search for information? How knowledgeable are you on the topic? What sources do you trust, and why?

The most reliable knowledge at any given time is a scientific consensus. Therefore, for any topic outside your area of expertise, your best bet when “doing your own research” is to find the consensus (if there is one).

What is a consensus? And why is it trustworthy?

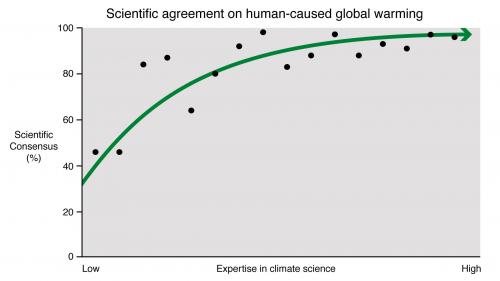

Scientific research these days is highly specialized, with each subfield having its own nomenclature, methodologies, statistical analyses, etc., required to represent and communicate its nuance and complexity. Experts have the knowledge, skills, and experience necessary to evaluate the quality of evidence provided by any particular study, and importantly, to put it into context with the larger body of literature. Scientists researching heart disease are not trained to understand the literature on black holes, for instance, or even eye diseases. (Note: This goes for any of us outside of our area of expertise. The scientific literature is where specialized scientists talk to each other. It’s not for non-experts.)

Contrary to how science is often taught in school, there is no single scientific method. Instead, science is a community of experts using diverse methods to gather evidence and scrutinize claims. The social aspect of science is a major reason it’s so reliable, as there’s a systematic way to correct for the biases, errors, and even fraud of individual scientists.

At the heart of the process of science is peer-review, in which research must pass the critical scrutiny of other experts before it’s published in a scientific journal. However, a single study is never the final answer: conclusions must be replicated and fit in with the larger body of evidence before scientists will accept them.

Sources: Steinberg, et al (2017); Peter Hess, Inverse

When independent and diverse lines of evidence converge onto a conclusion, the conclusion is considered strong, and experts generally accept it. The result is an expert consensus, or the collective position of experts based on an evaluation of the body of evidence. The consensus isn’t the final word, but the starting point upon which the vast majority of experts agree. (Note that a scientific consensus can refer to both the collective position of evidence and/or experts.) Scientists can then build upon the foundation of knowledge that was gained through the process of science to learn more about what they don’t know.

The consensus is likely incomplete and it’s open to challenge, but it’s very unlikely to be completely overturned. If there is a problem with the consensus, non-experts almost certaintly aren’t going to find it with their “research”… it’s going to be an expert who does. And because the incentive structure in science rewards scientists who discover new things or prove established knowledge wrong, overturning the consensus would be a career-winning strategy, the kind of which Nobel prizes are made. The likelihood of thousands of scientists giving up fame and fortune for the sake of maintaining a conspiracy, as suggested by many denialists and pseudoscience promoters, is next to none.

Most people generally trust experts and use the consensus as a short-cut for decision-making. For example, if five electricians told me the wiring in my house was in danger of starting a fire, I would almost certainly get it fixed! Industry denial campaigns, such as those by tobacco and the fossil fuel companies, know full well that the public trusts the expert consensus, which is why their strategy includes telling the public there isn’t one, using bulk fake experts to counter a real consensus, or even suggesting consensus isn’t a part of the process of science.

One reason for the confusion around the importance of consensus in science is that the word has different meanings. For many of us, it’s a popular opinion or general agreement. But expert consensus isn’t the result of group-think, and it isn’t democratic. It’s the result of highly specialized experts independently evaluating the body of evidence and arriving at a similar conclusion. No other system of acquiring knowledge is as reliable or trustworthy, and it’s due largely to the community of experts checking each other’s work.

Finally, it’s not an appeal to authority to accept the consensus of experts. It’s the prudent thing to do! What is fallacious is appealing to those who aren’t experts, are experts in another area, or who represent a minority opinion to support a claim. If you value expert opinion, the consensus position should matter more than a cherry picked “expert.”

In short, the expert consensus is the most reliable form of knowledge for non-experts.

How to find a consensus (if there is one)

Sometimes a consensus is measured by gauging expert opinion while other times it’s by evaluating evidence. It can take significant time and research for experts to reach a consensus, and some issues have more agreement than others. That said, some topics that are controversial from the public’s standpoint (e.g. evolution, climate change, safety of vaccines) are about as settled as science can get.

Finding the consensus, if there is one, can be challenging, but it’s still orders of magnitude easier than doing all the research yourself.

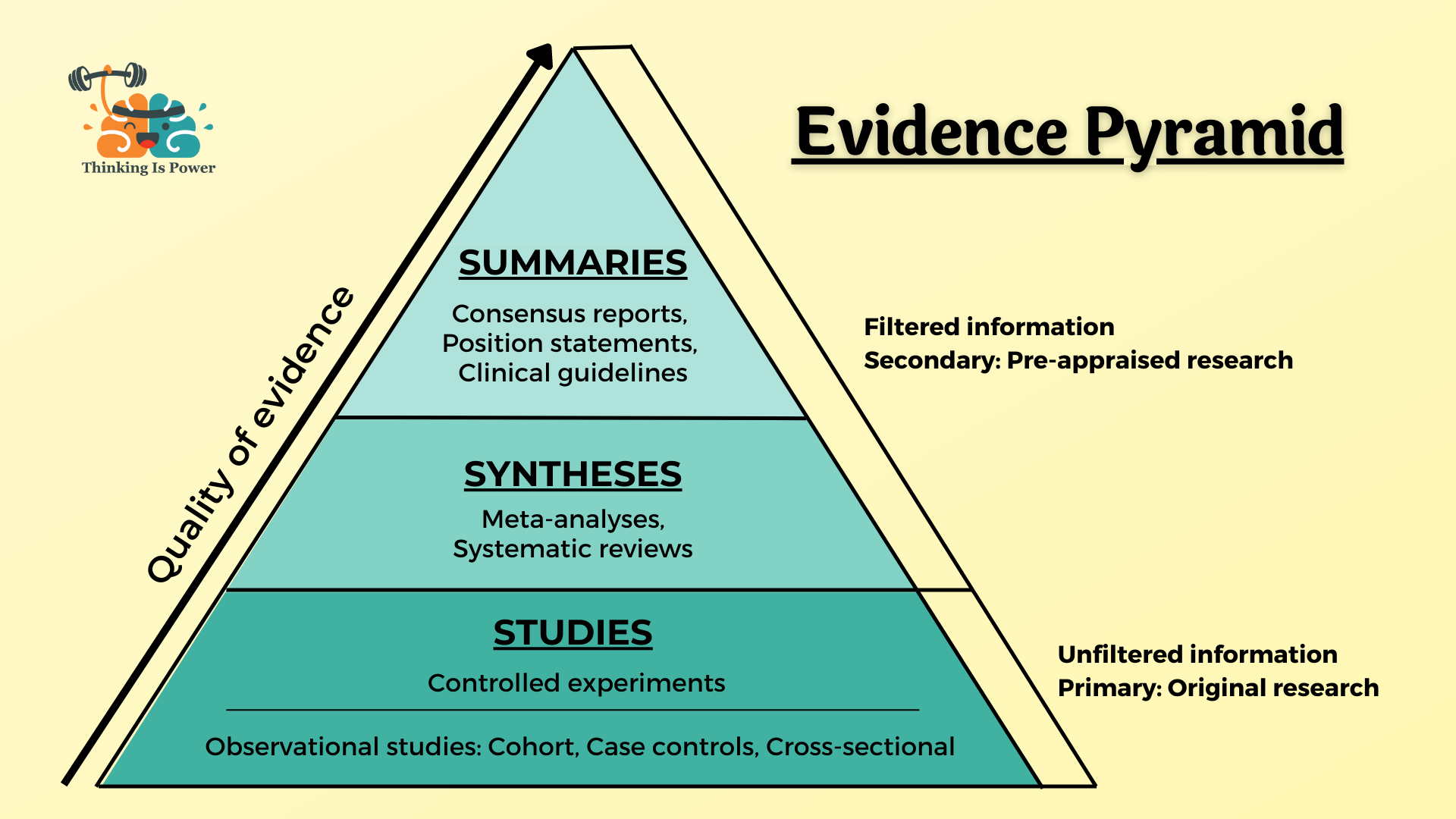

–Research syntheses combine the results from studies to assess the weight of the evidence. Systematic reviews synthesize the literature and condense what’s known on a given question while meta-analyses are systematic reviews that use statistical methods to summarize the results.

Remember that individual studies aren’t the final word. If individual studies are like pieces of a puzzle, these papers help to put the puzzle together. Essentially, systematic reviews and meta-analyses help us avoid the trap of potentially being misled by a single study.

To find research syntheses, search for your keywords and the words “systematic review” or “meta-analysis.” (The non-profit Cochrane Library is an excellent resource for medical research syntheses.) As always, be sure to check the quality of the journal, and keep in mind that syntheses are only as good as the research that goes into them.

–Consensus reports are syntheses of syntheses. (Yes, it’s very meta.) Consensus reports aren’t always available, but if they are, they provide excellent evidence of a consensus.

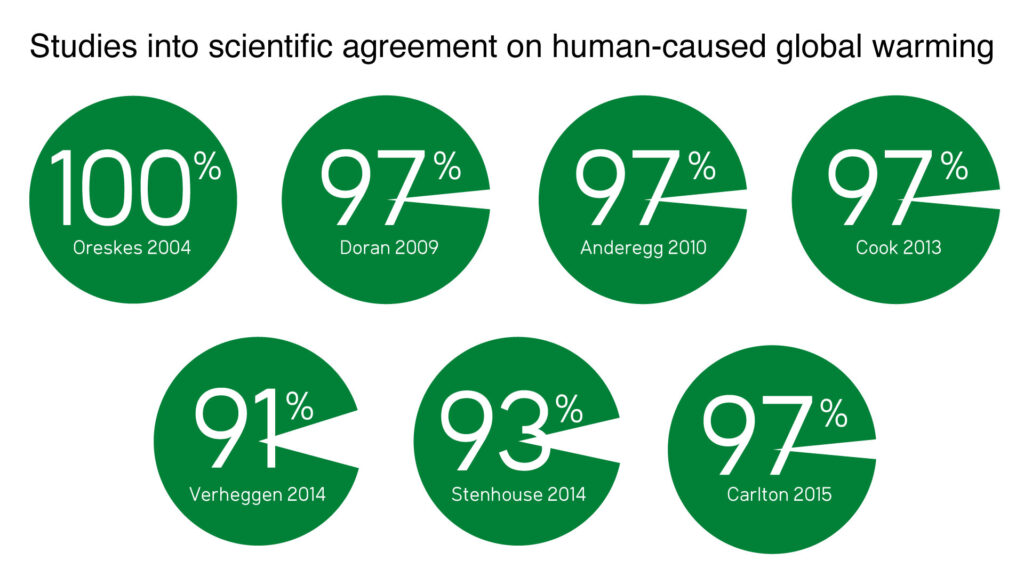

The best examples of consensus reports come from climate change research. For example, Cook et al (2016) synthesized the consensus estimates from six independent studies and found a robust scientific consensus that humans are causing the climate to change.

(Cook et al. 2016). Illustration: John Cook. Source: Skeptical Science

Another example from climate change research is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Every few years since 1988, the IPCC selects top scientists from around the world to evaluate and synthesize thousands of climate-related studies to provide the most reliable and comprehensive assessments about the causes, impacts, and future risks of a changing climate. (Their most recent assessment states, “It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land.”)

To find a consensus report, search for your keywords and the phrase “consensus report,” “synthesis report” or “research synthesis.”

–Position statements are official points of view on scientific issues by reputable scientific organizations and/or professional societies. These reports are generally based on reviews of published literature and are typically the most common expression of a scientific consensus.

To find position statements, search for your keywords along with a relevant scientific body. If you’re unfamiliar with the scientific organizations regarding a particular issue this may take a bit of searching. (However, it’s also a good indicator that searching for the expert consensus is a better choice than trying to read the literature.) Be wary of front or astroturf organizations that create unreliable societies to promote pseudoscience or science denial.

Examples of authoritative governmental scientific organizations, non-profit organizations, or professional societies include:

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- National Science Foundation (NSF)

- American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)

- American Medical Association (AMA)

- National Academy of Sciences (NAS), especially the Based on Science section

A very reliable indicator of consensus is if the majority of prestigious organizations have arrived at a similar conclusion.

–Clinical practice guidelines are recommendations produced by various healthcare organizations and medical professional bodies to help clinicians diagnose and treat patients using the best available evidence. These statements are based on systematic reviews and generally the consensus positions of experts in their relevant medical fields.

[Finding clinical practice guidelines.]

–Polls and surveys measure scientists’ opinions on a topic. While these provide useful information, especially if the results are in line with other measures of the consensus, they aren’t as reliable as literature reviews.

As always, it’s important to use credible polling organizations. In addition, pay attention to who was surveyed. Was it all scientists? Top scientists, such as those in the AAAS? Were they experts in their fields?

A few more tips for your search

We’re more likely to fall for misinformation when it confirms what we already believe. If you’re looking for evidence that you’re right, you will absolutely be able to find it online! So instead of asking Google a leading (or loaded) question, use neutral search terms. Or better yet, break out of confirmation bias by trying to find evidence that you’re wrong.

It’s essential to check the reliability of sources. While peer-reviewed journals are the most reliable source of scientific information, not all are created equal. One way to check the quality of a journal is to search for its Journal Impact Factor (JIF), which calculates its influence in the scientific community based on the number of times its articles are cited.

Unfortunately, the more dangerous forms of deceit online involve setting up fake science journals or organizations to promote pseudoscience or denial, and it can be easy to fall for “studies” that appear to be scientific but are of significantly lower quality. In particular, be wary of predatory journals that publish false or misleading information and lack quality publication practices and pseudoscience journals that pretend to be scientific but are created for the sole purpose of publishing fake science.

If you’re using sources of information that aren’t peer-reviewed, it’s even more important to check its reliability. Don’t waste time on an unknown site’s “About” section, instead look laterally to see what other reliable sources have to say.

[Learn more: Don’t be fooled…fact check!]

The take-home message

While many of us like to think of ourselves as independent thinkers, most of our beliefs come down to the sources we choose to trust. Unfortunately some have decided that “thinking for themselves” means automatically not trusting information from the government, the media, or even academia, leaving them vulnerable to misinformation that reinforces their existing beliefs or biases.

We trust experts all the time, to grow our food, to fly our planes, to wire our homes, etc. It’s only when expert opinion conflicts with our core beliefs that we resort to denial… and to “doing our own research” to find the “real truth.” Instead of cherry picking studies or experts to try and support your cherished beliefs, be honest with yourself about what you believe and why… and why you trust the sources you do.

But you can’t out-research experts. You have to be an expert to do that. If your “research” leads you to sources that tell you the experts are all mistaken or lying, you’re doing it wrong. You haven’t found trustworthy sources the experts have all missed. You’ve been misled by misinformation designed to appeal to your emotions or biases.

The bottom line is: If you want to believe in things that are “true,” to the best of human capabilities to know “the truth,” place your trust in the process of science and the resulting scientific consensus.

However, if you’re really convinced nearly all of the world’s experts are wrong, become an expert and do your own (real) research. (And win your Nobel Prize!)

To learn more

- Forbes: What does ‘scientific consensus’ mean?

- Credible Hulk: Scientific Consensus isn’t ‘part’ of the scientific method: It’s a consequence of it

- Medium: Scientific consensus: What it is and why this is a good time to start caring

- Time: Science isn’t always perfect – but we should still trust it

- Kyle Hill: How to read a scientific paper

Special thanks to Lynnie Bruce, Jonathan Stea, and John Cook for their feedback

Pingback: 2021 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #36 | Climate Change

Pingback: Thinking is Power: How to do your own research | Climate Change

“ Finally, it’s not an appeal to authority to accept the consensus of experts. It’s the prudent thing to do! What is fallacious is appealing to those who aren’t experts, are experts in another area, or who represent a minority opinion to support a claim. If you value expert opinion, the consensus position should matter more than a cherry picked “expert.” ”

this is logically false. this article is not scientific but philosophical. it primarily deals with epistemology.

do you consult with experts in epistemology?

who cares. epistemologists do not.

i’ve NEVER had a philosophy professor or colleague even mention their credientials. it’s irrelevant to any argument. it’s only value is to get poor thinking people to listen to one’s arguement because to they think it is somehow relevant.

Thank you for your comment.

Accepting the expert consensus is not an appeal to authority, as it’s not an appeal to any individual but to the collective community of experts. Everyone (including philosophers and epistemologists) relies on expert consensuses outside of their area of expertise.

The problem with the argument here is that it assumes the scientific community acts in an ideal fashion when in reality it consists of human beings subject to all the vagaries of social psychology such as motivated reasoning and pluralistic ignorance (spirals of silence) which can affect whole communities not just individuals, especially on morally charged questions. The bottom line is not to trust the experts it’s to employ critical thinking and yes, scientific method which is a real thing. Of course when you don’t find any serious evidence of collective cognitive distortions, your default will be to accept the expert consensus.

An example of social-moral pressures interfering with collective objectivity:

Oellerich, T.D. (1998). “Identifying and Dealing with ‘Child Savers’”, IPT Journal.

QUOTE:

<<<<<<<<<>>>>>>>>>

<<<<>>>>

Thanks for your comment.

To be clear, I’m not making that assumption at all. Scientists are people, and people make errors, have biases, and can even lie. That’s why the community of scientists is so important – they provide checks and balances. (When errors and fraud are found it’s because of the work of other scientists.) A major reason the scientific community is so reliable is because they are all incentivized to find “the truth”, whatever that may be. If experts have reached consensus it’s the best knowledge available to us.

Conversely, non-experts “doing their own research” online are almost certainly motivated by their own existing biases and beliefs yet do not have a community of other experts to hold them in check. Their lack of knowledge and lack of humility aren’t a good mixture and they’re likely to lead themselves astray.

Melanie

It looks like an HTML error snipped my quote illustrating pluralistic ignorance. Hopefully that won’t happen this time:

“Kilpatrick (1992) concluded that early child and adolescent sexual experiences, unless there was force or high pressure involved, had no influence on later adult functioning regardless of the type of partner involved (i.e., relative or non-relative) or the age differences. She reported that, when she discussed her findings with professionals, they closed their ears to them. They were most closed to those findings that indicated positive reactions to these early sexual experiences and to those findings that indicated that incestuous experiences did not cause irreparable harm.”

It may take time, but the process of science does work. Someone(s) in the community will eventually catch a bias blind spot. (As in the example you provided.)

Non-experts are certainly capable of critical thinking. They don’t, however, have the background knowledge and experience necessary to question the consensus…and that’s often what people who are “doing their own research” are seeking to do. The fact that you’ve been able to prove yourself wrong says a lot about your ability to question your beliefs – a mark of a critical thinker. But my guess is that you didn’t prove a scientific consensus wrong. It takes an expert to do that.

Thanks again for your comment.

Melanie

In the example I provided, that person and a few others have caught the blind spot,, and everyone else refuses to listen to them or to look at the evidence because they feel that doing so would morally taint them. This is how spirals of silence work.

Melanie has answered you, Eric. You are getting upset over ONE example. ONE study. Scientists are not going to throw away a scientific consensus over ONE example of bias. If further studies prove Kilpatrick correct, then I am sure scientists are not going to willfully ignore that much evidence. It would be preposterous for scientists to not take into account an emerging new body of evidence. Why are you such a maverick on this? If you don’t trust people who study a subject as their full-time career, then how can you trust that guy at the bar who has a blog? Your “gut” is flawed. It’s emotionally biased.

By my reference to pluralistic ignorance, I gave a clear example of how scientists do NOT always act as checks on each other’s biases, but rather can block each other from acknowledging unpopular truths. And saying non-experts are “almost certainly” motivated by their own biases is simply stereotyping. Non-experts are just as capable as experts of practicing critical thinking. I personally have had the experience of being led by doing my own research to disbelieve something I’d initially assumed was true.

There’s an analysis of the appeal to expertise in various books on argumentation schemes. The consensus is (heh) that appeal to expertise is much as described here. I would say there is more to scientific method than sociality, but it applies at the next level of abstraction and is hard to see. My correction to Walton and others would be to add to the critical questions: “Is this a field for which there can be experts?”

Thanks for your comment. Just to be clear, accepting the expert consensus is not an appeal to authority. It’s the prudent thing to do.

Your last question is an interesting one. A great example would be homeopathy: There’s no good evidence that it works, or even that it can work, (Harriet Hall would call it “fairy tale science”), so how can one be an expert in homeopathy?

Melanie

Hi,

I commented on your previous post and was directed here for an answer to my question. Unfortunately, I don’t think my concerns were sufficiently addressed by the contents of your blog. While you do go into detail about the methods in which one would use to find out expert consensus on scientific topics, this isn’t actually what I was concerned over. My question was more fundamental, namely, what reason do we have to trust our sense perception and critical thinking when it comes to something like your blog, but not scientific data that might very well be equally intuitive? In other words, if we can’t believe scientific data because we’re not experts, why should we even believe you?

If the answer is you yourself are an expert or appealing to expert testimony, I’m afraid that’s just begging the question. In order for people to believe what expert testimony says they need to be able to understand their words and the meaning behind them, to do this there has to be some level of confidence in their own knowledge, in spite of things like the Dunning-Kruger Effect, Confirmation Bias, etc, which are ever present throughout our lives in everything we study. Yet these limitations suddenly become irrelevant when it comes to a laymen’s ability to understand expert testimony, in spite of them being the very reasons why laymen are supposedly unable to fully understand scientific literature in spite of any independently acquired knowledge.

I’ve yet to hear a justifiable symmetry breaker between these two things that don’t involve some type of special pleading, leaving us with only two options. Either laymen are unable to understand anything regarding science, including this very blog, or laymen are able to understand science assuming they have the proper knowledge, which would undermine the argument you’re making here.

Hello! Thanks for your question.

I’ve done my best to summarize why we should trust the expert consensus, but for a more detailed explanation I would suggest reading Naomi Oreskes’s “Why Trust Science.” (Or at least consider starting with this article in Time.)

While this site tends to emphasize scientific experts, lots of people rely on others like journalists, government officials, celebrities, and social media influencers for expertise. Many questions, like “was the 9/11 attack a government conspiracy?” or “did Trump misuse his power by trying to get Zelinsky’s help against Biden?”, are important but won’t be settled by scientific studies. Scientific subjects can vary from quantum mechanics to political science and will vary widely in terms of how much experts agree and how difficult it would be for us to form an intelligent independent opinion.

Of course a crucial starting point is that we’re looking for a realistic understanding and not trying to confirm an existing opinion or push an agenda. We also must recognize that we’re often going to have to settle for what is most likely rather than what is definitely true. I’m happy this site stresses this so strongly.

While experts typically know more than us, an awful lot of very misguided convictions result from people latching on to those they wrongly believed were experts. These may be celebrities or powerful current or historic leaders or religious zealots. We shouldn’t idolize any authority.

It’s useful to think about the motives of experts. Researchers at universities normally expect to benefit from being right, so we can trust them more than people associated with an ideology or special financial interests.

If the subject isn’t too technical I like to form my own opinion based on facts that don’t seem to be in dispute. An expert opinion can be wrong, but recognized experts will rarely be wrong about facts that could easily be checked, otherwise they soon wouldn’t be recognized experts. We should try to make sure we understand the best arguments on both sides of an issue before we form too strong an opinion.

Hi, nice article. For a long time, I used my “method” for doing research, which I think achieves reliable results, but this article (and the previous one) made me wonder whether this method is really that good. It usually takes six steps:

1. Mental preparation. In the first step, I usually convince myself that I can be wrong and try to get rid of emotions if the topic is emotionalizing. Then I read some articles that disagree with my opinion (if I had any opinion before) to weaken the confirmation bias. I’ve heard that many people don’t change their minds after doing research, and I don’t want to fall for this trap.

2. Reading Wikipedia. I know that Wikipedia is not the most reliable source on the Internet, at least compared to peer-reviewed journals, but making conclusions is not the point of this step. Instead of this, I (usually) read the whole article (as this site explains many topics pretty well, with understandable language) to get an overview and understanding of topics that I’m researching.

3. Checking more reliable sources. In the second step, I read sources that are considered reliable, but “normie-friendly,” such as some pop-science magazines, articles in scientific journals, or online encyclopedia pages (as Britannica). This step provides more diverse sources than only Wikipedia and is also focused more on understanding the topic than making conclusions (but if an article in a scientific journal states a conclusion, I note it). I usually use duckduckgo search engine and neutral search phrases as Google tends to promote information that I already agree with.

4. Checking university sites. Usually after doing the previous three steps, I search my question with “site:edu” filter and select sites that belong to universities. After reading about 10–20 articles, I already know some arguments for and against my hypothesis and some mistakes that scientists may make in their papers that I should be aware of.

5. Reading scientific papers. I usually use Google Scholar to find papers about my research topic and try to read every paper that addresses my question (if some papers are paid, I usually look for them on Researchgate, as this site occasionally provides them for free). I also weight papers based on their kind and what method they use, and filter them to only use more recent papers, if necessary (https://ibb.co/vxnRXfJ). If the answer depends both on scientific evidence and philosophical beliefs (f.e. in case of questions about the morality of animal testing, the answer from utilitarian point of view would be slightly different from answer from Kantian point of view), I try to find answers for all popular philosophical points of view.

6. Summarizing my research. In the last step, I make a conclusion based on my previous research. If I managed to find only very few papers, I make conclusion based mostly on the third and fourth step. If I found more papers (which happens more often), I make a conclusion mostly on the last step.

Sometimes when I don’t have so much time or I just need a quick answer, I’m doing only 1st and 5th step, but I prefer doing all steps, as it gives me much more understanding and knowledge about the desired topic and, in my opinion, leads to more valuable and complex answers. So now I have three questions for the author.

– How reliable is this method? Are there any flaws that can lead to confirmation bias or misleading results?

– What can I change in this method to make it more reliable and to get a deeper understanding of the researched topic?

– How to check whether my research is biased?

– Should I consider references of articles equally to papers I found independently?

Also sorry for bad English, as it’s not my native language.

Wowsers! I wish I could add something, but I think your method is pretty darn great.

If I’m nit picking, my only comments/suggestions would be:

-Monitor not only your biases and emotions, but your knowledge. In particular, have an awareness of what you don’t know.

-When looking for research papers, check the quality of the journals and be especially wary of any study that says something well outside established knowledge.

-Check for the consensus of experts. This might be especially interesting after you’ve done your “research”, as you can see if the experts came to a different conclusion. If so, explore why.

Your English is excellent. Might be better than mine. 🙂

Thanks for the comment!

Melanie

Thanks!

I have one more question. Is https://mediabiasfactcheck.com accurate?

It is recommended by some sites:

https://libguides.volstate.edu/evaluate/news

https://libguides.nsu.edu/c.php?g=647162&p=4540895

https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/news

https://csus.libguides.com/c.php?g=824928&p=5924793

But others seem to point that method used, by this checker is unscientific and yields inaccurate results:

https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2018/heres-what-to-expect-from-fact-checking-in-2019/

https://www.cjr.org/innovations/measure-media-bias-partisan.php

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Media_Bias/Fact_Check

https://www.politifactbias.com/2017/10/can-you-trust-what-media-biasfact-check.html

https://www.justfactsdaily.com/media-bias-fact-check-incompetent-or-dishonest

Sources that recommend using mbfc seem to be more reliable than, these that don’t, however some of those that don’t recommend using it, go deeper and point out concrete mistakes in their method (while the first group just mentions this checker). I have also seen that rationalwiki is rated as more factual than Wikipedia, or that their extension rated their own fact-checker with highest possible rating (when according to their methodology, if they are reliable, they seem to have “high” Factual Reporting Score, instead of “very high”, which is very hard to achieve), which seems a bit suspicious. I’m pretty confused, by this because this fact checker is widely recommended, but its method is criticized. What do you think about it? Do you know some better sites, similar to that one?

Thanks for the comment, and sorry for the tardy response!

When I’m trying to determine if a source is reliable, I use several sources – not one – because like science, conclusions should be replicable. My three “go to” sites are Ad Fontes (and their new interactive chart), All Sides, and Media Bias/Fact Check. Each of them will list results for bias and accuracy, along with their results. If all three sites generally agree the conclusion is more reliable.

Thanks for the great question. Hope that helps!

Melanie

I am surprised but not shocked by the number of people here arguing with you against scientific consensus. I suppose, given American ideology and the promotion of “rugged individualism” over community and social bonds, that this makes sense. It also tells me that America still seems to be in its infantile stage of self-awareness and scientific understanding. Sure, no one’s perfect, including scientists. But scientists as you mention work together to find flaws in each other’s reasoning. Internet warriors do not.

I think what’s going on is everybody wants to be hailed as the “expert.” We all feel like contestants on American Idol, hoping a Simon Cowell hits the golden buzzer and we can sail through to the final round. The posters here who have called into question your valuable assertions about scientific consensus all want to skip the messy, and very time-consuming, process of collaborating with others (and possibly being told they’re wrong) and go right to the last stage: being hailed as the new, unassailable expert on something.

If only it worked that way. If only the internet hadn’t scared us silly already with conspiracy theories and caused so many to doubt science.

Pingback: Hvordan vite hva som er det beste nettcasinoet for deg?

Pingback: Jak samodzielnie weryfikować informacje? - naukaoklimacie.pl

Pingback: How To Know If You're Thinking For Yourself - the Conscious Vibe

Pingback: How To Know If You’re Thinking For Yourself – LAH SAFI Y