In 1900, the average life expectancy at birth in the United States was 48. By 2020, life expectancy had increased to 79, thanks largely to modern medicine, especially antibiotics and vaccines. (Although flushing toilets helped, too!) Ironically, the leading causes of death today, like cancer and heart disease, are chronic conditions that develop mostly in older people.

Modern medicine uses science to determine what causes illnesses and how best to treat them. Personal experiences (like “I tried it and felt better”) aren’t sufficient evidence, as our minds can easily deceive us. Therefore, medical researchers test treatments with carefully controlled experiments to remove as much bias as possible, and a treatment isn’t considered effective unless it performs better than a placebo.

Importantly, all drugs and treatments have to be tested and shown to be effective and safe. All side effects are documented. And the products are quality controlled: there’s no contamination and the package contains exactly what’s on the label.

Is the system perfect? Absolutely not. But it’s better than not having one.

Which leads me to…

What is alternative medicine?

Alternative medicine (AM) refers to practices that are used instead of conventional medicine. While there are countless examples, some of the more common ones include naturopathy, homeopathy, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, reiki, acupuncture, chiropractic, supplements, and some diets.

Alternative treatments are quite popular, and it’s easy to see why people fall for their allure. Let’s start with the obvious: our healthcare system has problems. Too many are uninsured, or underinsured, and compared to other wealthy nations, Americans spend twice as much on healthcare yet have worse outcomes. In addition, AM is often promoted as “natural” or “traditional,” labels that make the treatments seem safer or more effective but in reality mean very little.

But most of all, AM entices patients by offering hope and a sense of control, however false and empty those promises are. Unfortunately, sometimes modern medicine can’t solve what ails us. Whether it’s a chronic condition like migraines or a potentially fatal one like cancer, science may not yet (or ever) have the answers.

However, by definition, alternative treatments haven’t been shown to be effective, or they would be medicine. This is a problem for AM practitioners, of course. It’s dangerous to use unproven treatments instead of evidence-based ones. Therefore, proponents often combine conventional medicine with alternative practices, giving it names like complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), integrative medicine, and functional medicine.

Not only do alternative treatments lack evidence, most are outright pseudoscience. Many lack a plausible mechanism for how they might work. Nearly all rely on anecdotes or poorly-designed, cherry-picked studies that are published in low-quality journals. And proponents regularly claim the reason mainstream medicine doesn’t take them seriously is because they’re conspiring against them, purportedly so “Big Pharma” can make money.

Conspiracy accusations misunderstand something fundamental about science: Science’s incentive structure rewards those who either disprove a longstanding conclusion or discover something new, like the effectiveness of an alternative treatment. And as for money, it’s true that Big Pharma is profitable, but Americans spend over $30 billion a year on CAM. Additionally, as of 2015 the federal government had spent over $5.5 billion trying to prove the effectiveness of alternative treatments.

(Scientists have widely criticized the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, which has a political mandate from Congress, for spending taxpayer funds on pseudoscience.)

If alternative medicine doesn’t work, why did it “work” for me?

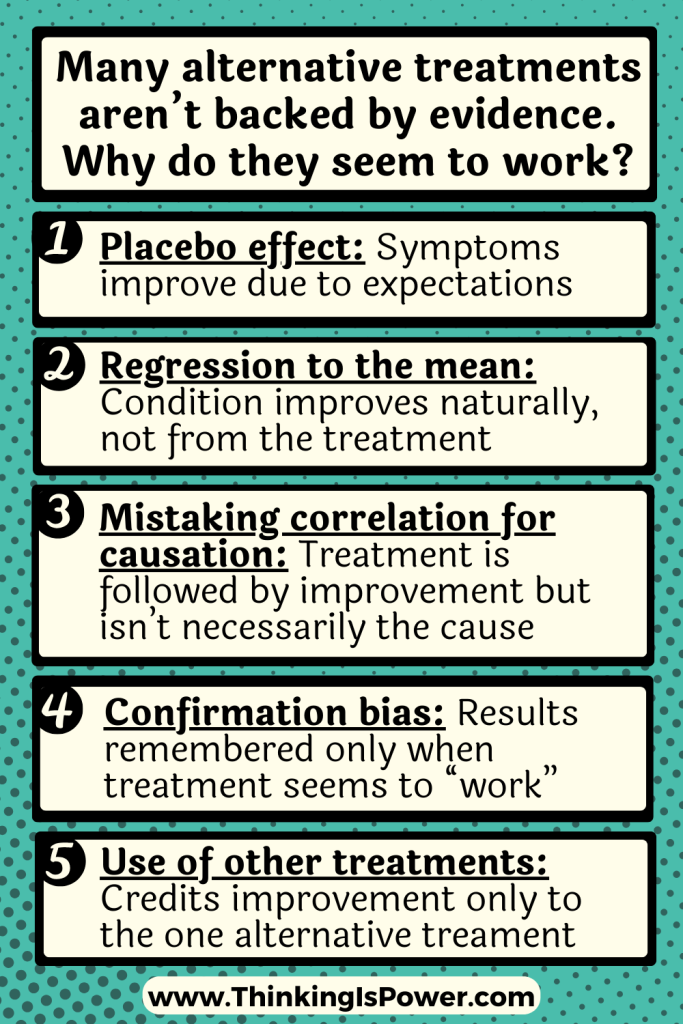

While many alternative treatments aren’t backed by evidence, some will claim they’re effective because they tried them and felt better. It’s an understandable response, as we trust our experiences. But if anecdotes were sufficient evidence, science journals would be full of them. There’s a reason treatments are tested in carefully controlled experiments: the process of science is designed to recognize and correct for the many ways we can fool ourselves.

So if an alternative treatment isn’t effective, why did it “work” for me?

- Placebo effect: A placebo is a substance with no therapeutic value. Yet the act of being “treated” by a placebo can result in an improvement in symptoms, ie the placebo effect. That’s why treatments aren’t considered effective unless they perform significantly better than placebos. Alternative treatments haven’t, so any perceived improvement in symptoms is due to our expectations and not the actual treatment. (Note: Since placebos have no therapeutic substances they can only “treat” subjective symptoms. Our minds aren’t actually curing us!)

- Regression to the mean: Abnormal or extreme events tend to be followed by more moderate ones. Some ailments, like headaches, colds, or warts, heal on their own. Others, like rosacea or cold sores, cycle. But in all these cases, unless you die you will likely improve. So it’s possible the alternative treatment wasn’t the reason you felt better – you were just going back to your normal state of health.

- Mistaking correlation for causation: It’s human nature to search for explanations by finding patterns and connecting the dots…and then assuming that because two things occurred together one caused the other. For example, let’s say you took Echinacea and your cold went away, so you assume Echinacea treated your cold. Determining causation is tricky business, however, and requires studies that control for other variables that may be behind the correlation. In the case of colds, Echinacea doesn’t work, so unfortunately, you mistook a correlation for causation.

- Confirmation bias: Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, favor, and remember information that confirms what we believe, and it is the most powerful and pervasive bias of them all. For example, if you believe that acupuncture treats pain, you’re likely to notice signs that you’re feeling better and overlook signs that you’re not. Or you may remember the times it “worked” but not the times it didn’t.

- Use of multiple treatments, but only remembering the one: This is the lifeblood of CAM, integrative medicine, and functional medicine, which use alternative treatments alongside evidence-based ones. Essentially, these practices “complement” actual medicine with placebos. For example, a cancer patient undergoing radiation therapy may also may use acupuncture and homeopathy, but due to confirmation bias may attribute their healing only to the alternative treatments.

In short, anecdotes aren’t good evidence for a reason: we can easily be misled by our personal experiences. So if well-designed studies have demonstrated that a treatment doesn’t work, but it “worked for you,” consider that you might be fooling yourself.

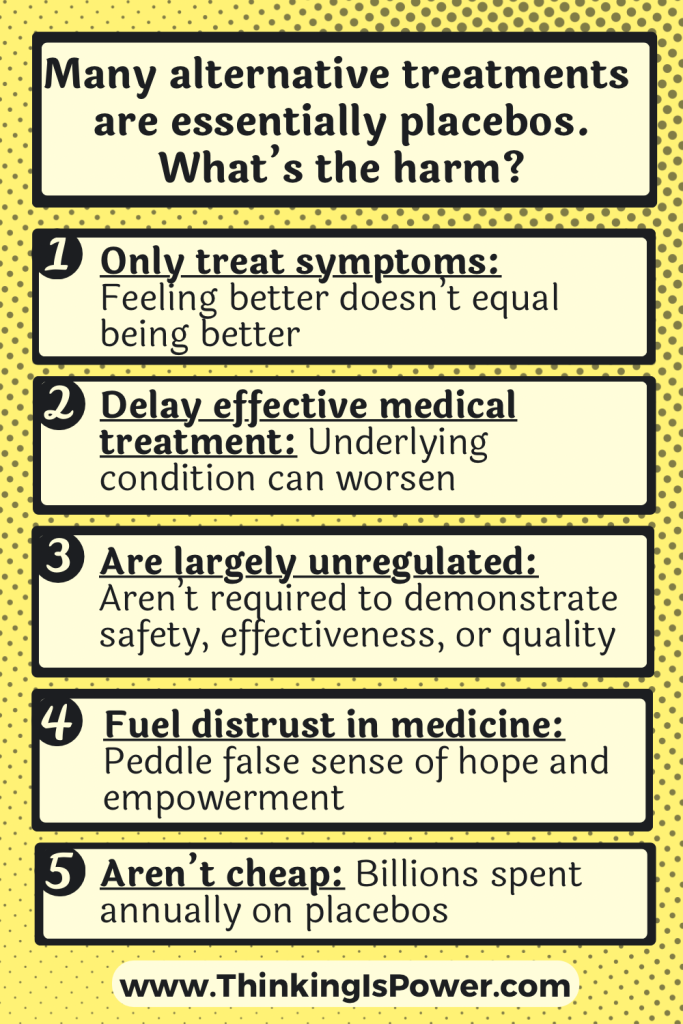

But if it “works” for me, who cares? What’s the harm?

Even after hearing that alternative treatments are placebos, people often respond by saying, “But I felt better.” I get it…the placebo effect is real. But it’s important to be aware of potential harms of placebo medicine.

- Placebos only treat symptoms: Placebos are relatively effective at treating pain and other perceived symptoms of illnesses or diseases, but they do not treat the underlying condition.

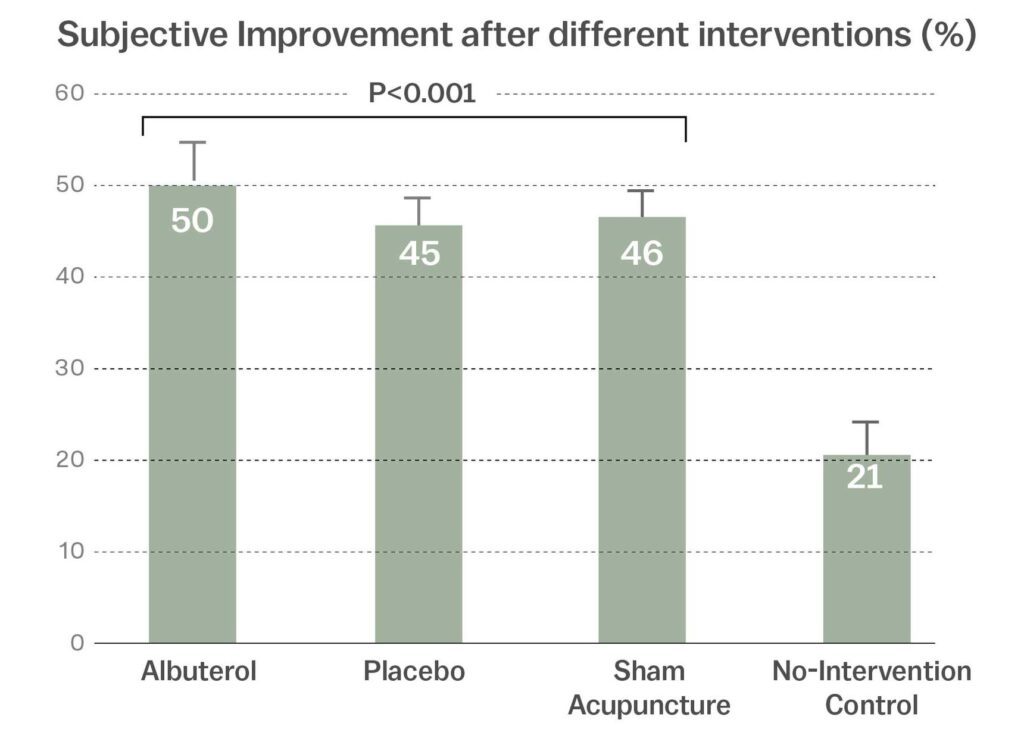

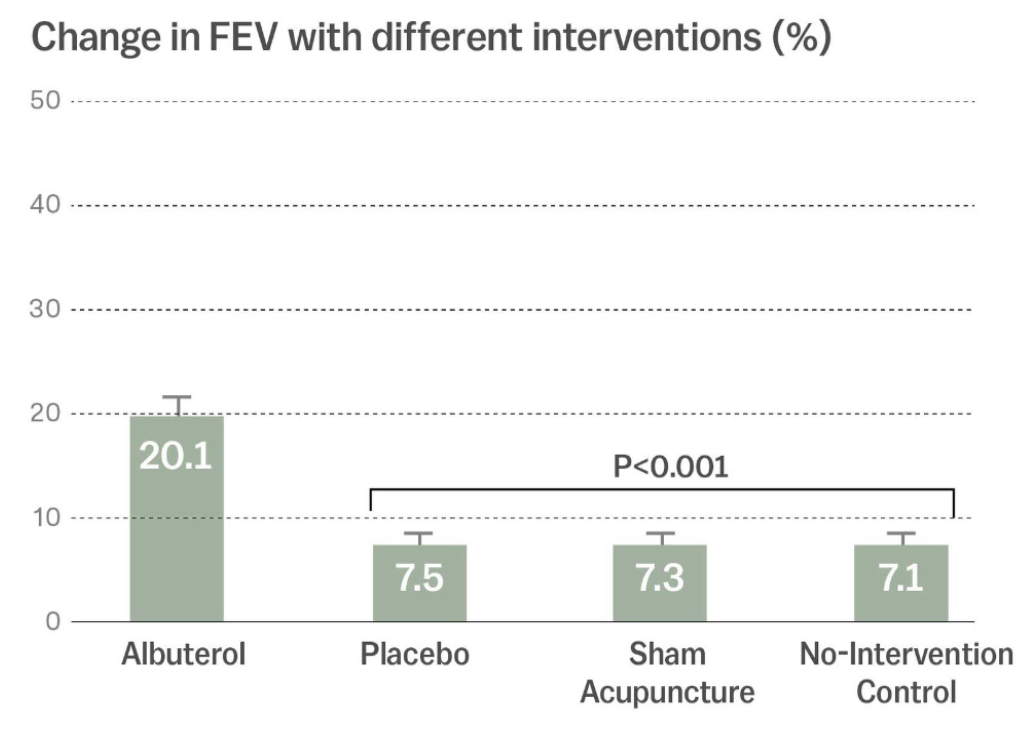

In a 2011 experiment, asthma patients were randomly put into either a group that received an inhaler with albuterol (a drug that relaxes the muscles around airways, opening them up), a group that received an inhaler with a placebo, a group that got “sham” (ie placebo) acupuncture, or a group that received nothing. Researchers measured two outcomes: the subjective self-reported change in asthma symptoms and an objective measure of lung functioning. Self-reported symptoms improved for all groups who received treatment. However, and this is important, only the albuterol actually improved airflow.

[Source: The weird power of the placebo effect (Vox)]

[Source: The weird power of the placebo effect (Vox)]

Symptom improvement is obviously important. However, only the albuterol improved the symptoms AND treated the underlying condition.

- Delaying effective medical treatment: If you’re using placebos to replace or delay evidence-based medical treatment, underlying conditions can worsen. For example, cancer patients who initially use alternative treatments, as opposed to conventional ones, are nearly five times more likely to die.

- They aren’t regulated: While the FDA requires that conventional treatments are tested to demonstrate they’re effective, safe, and quality-controlled, alternative medicine is largely unregulated. For example, there are no FDA-approved homeopathic products and supplements are exempt from FDA regulation, as noted by the disclaimers on the bottles. The lack of regulation means they don’t have to back up their claims with evidence, they aren’t required to demonstrate their products are safe, and there’s no quality control.

This has real consequences for consumers. Supplements aren’t supposed to claim their products treat specific diseases or illnesses, so they often make broad, sweeping statements which many mistake as meaning they’re highly effective. Many people assume supplements and homeopathic remedies are “natural” and therefore safe, but supplements can cause liver damage, cancer, and even death. The lack of quality control means the bottle may not even contain what it claims or it’s contaminated with heavy metals or harmful bacteria.

And unlike the risks of conventional medicine, the risks of supplements come with essentially no benefit.

- Fuels distrust of conventional medicine: Many who use AM are looking for what they view as “natural” and “safe” alternatives to conventional medicine. Others may have health problems that are difficult to treat and are looking for hope. And in the U.S., healthcare is big business, which many (understandably) view as greedy and corrupt. AM proponents play into these hopes and fears, using them to convince vulnerable and trusting patients to instead use their products and services. Unfortunately, this can cause patients to opt out of evidence-based treatments and into unregulated, unsupported “treatments.”

- It’s not cheap: Personally, I’m too cheap to spend my money on things that don’t work…and alternative treatments are placebos.

The point is, AM isn’t necessarily “safe,” so if you choose to use alternative treatments, make sure you’re aware of the potential harms.

The take-home message

Alternative medicine offers hope and simple answers to complex problems. But what may feel like empowerment and a sense of control are illusions… and potentially harmful ones.

Our healthcare system may have room for improvement, but it’s full of caring scientists and medical doctors who actually do want to help patients. And they aren’t conspiring against proponents of alternative treatments: If alternative practitioners believe their treatments work, they’re free to design quality studies to demonstrate evidence of their effectiveness.

However, as it stands, they haven’t. Instead, they sow doubt and distrust in evidence-based medicine and push unproven treatments onto unsuspecting patients. The fact that some practitioners may actually believe in the treatments they’re promoting speaks to the power of the human mind to deceive itself.

The next time you’re trying to decide between conventional medicine and alternative medicine, remember this: “Big Pharma” has to demonstrate that its products are effective and safe, and that what’s on the label is what’s in the bottle.

“Big Placebo” is after your money, too, without those pesky details standing in their way.

As always, thinking is power.

Special thanks to Jonathan Stea for his feedback.

I agree with everything you have said here. But when medical professionals can’t explain chronic illness, and can only offer medications that has a low rate of success and also side effects, the cure is worse than the disease. That’s when it seems reasonable to cautiously explore alternatives that may at least relieve symptoms.

I agree with everything you just said. I highly recommend this TEDx talk by Lydia Kang, “The Truth about Quackery,” for more on why it’s dangerous. My favorite line: “Hope can be hazardous to your health.

Consider the possibility that your article is hasty generization, an example of UNCRITICAL thinking?

The article’s position on CAM reflects that of the expert consensus. I understand that it can be difficult to admit that alternative medicine is a placebo, especially if we’ve used and spent money on it, and even more so if it’s become part of our identity. But the evidence to support CAM just isn’t there.

You mean the biased, subjective consensus. As an example, please explain how Homeopathic medicine can register effect on animals, plants and unconscious humans and animals?

You might like to look up the research Charles Darwin did with Homeopathy and plants. It rather horrified him but he had no choice but to admit that Homeopathic medicine used on plants demonstrated effect. How do you think the placebo effect works on plants? We cannot blame Darwin since he entered into the experiment believing it could not work and seeking to demonstrate it did not work. How would you explain it?

The burden of proof is on the person making the claim, in this case that homeopathy is more effective than a placebo.

Anecdotes and claims of bias aren’t evidence.

Melanie

> As an example, please explain how Homeopathic medicine can register effect on animals, plants and unconscious humans and animals?

Explained here: https://www.painscience.com/articles/placebo-power-hype.php#animal-placebo

What a great article about placebos. Thanks for sharing!

Melanie

Your first para has no substance in fact or history. As some good research would reveal. The greatest contributor to longevity and reduced mortality and infectious disease incidence was NOT modern medicine but improvements in sanitation and hygiene most particularly, better nutrition and the invention of refrigeration.

The claims you make have been common in the science-medicine industry for much of the past century. But that does not make them true and as someone defending real, legitimate and responsible science, you should have done a better job of research.

In 1977, Boston University epidemiologists John and Sonja McKinlay published a seminal work on the role vaccines (and other medical interventions) played in the massive decline in mortality seen in the twentieth century.

The McKinlay’s study was titled, “The Questionable Contribution of Medical Measures to the Decline of Mortality in the United States in the Twentieth Century.” Their data showed:

“that the introduction of specific medical measures and/or the expansion of medical services are generally not responsible for most of the modern decline in mortality.”

In 1970, Dr Edward H. Kass, of Harvard, gave a speech to the annual meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, of which he was then President. He warned his colleagues that drawing false conclusions about why mortality rates had declined so much could cause them to focus on the wrong things.

He said:

“…we had accepted some half truths and had stopped searching for the whole truths.

The principal half truths were that medical research had stamped out the great killers of the past —tuberculosis, diphtheria, pneumonia, puerperal sepsis, etc. —and that medical research and our superior system of medical care were major factors extending life expectancy, thus providing the American people with the highest level of health available in the world.

That these are half truths is known but is perhaps not as well known as it should be.

And take Measles as a case to refute your claims:

Early in the last century, measles killed millions of people a year.

Then, bit by bit in countries of the developed world, the death rate dropped, by the 1960s by 98% or more.

In the U.K., it dropped by an astounding 99.96%.

AND THEN, the measles vaccine entered the market.

Lawrence Solomon: The untold story of measles

In 1900 the average life expectancy at birth was low, but at the same time, only one in more than ten got Cancer and now it is one in two. We have today rates of serious and chronic diseases, including Cancer, never before seen and worse in children so whatever modern medicine might do it is not improving health.

The reason why people live longer is pure statistics. Because more survive the first five years of life because of improvements in sanitation, hygiene and nutrition, at least in the Western world, then there are more people percentage wise who will reach greater ages. Yes, antibiotics have helped with things like Scarlet Fever, for which by the way no vaccine was ever made, and Diptheria, but abuse of that valuable resource means we are fast losing that option.

Vaccinations have made little difference except that the health of children has declined dramatically from the Seventies when vaccinations went from 2-3 at older ages, with no pressure to conform, to more than 50 in the first five years of life beginning within hours of birth if not in utero. And all of the diseases for which children are vaccinated still exist, with many returning and others mutating, like Vaccine Derived Polio.

Your credibility would be better if you actually do the research with the sort of open mind that good science and safe medicine requires.

Much of your information is from the Children’s Health Defense, which is not reliable; it’s chairman, RFK, Jr, is one of the Disinformation Dozen. I would encourage you to reconsider where you get your information.

Agree with this article. Traditional medicine is safe and has been around for a very long time. Medical research has cured some disease given us a longer lifespan. Many people are living much longer now than they ever did in history. However, what about diet? What about consuming the right food in the first place? The article doesn’t mention about eating healthy organic food.

Hi Verna,

We can’t know whether a medicine is safe and effective by tradition alone – that’s why we need to study it! And diet is certainly an important part of health, but it’s outside the purview of this article. (That said, generally speaking, organic food isn’t safer or healthier. It’s also not what most people think it is. But again, that’s a topic for a different day.)

Thanks for the comment!

Melanie